Nestlé Africa’s baby food sugar scandal

Laurent Gaberell, November 18, 2025

Last year, we highlighted Nestlé's double standard over sugar in baby food, unleashing a wave of indignation across the world. In India, where this scandal caused a drop in its share price, Nestlé announced the introduction of 14 new Cerelac variants with no added sugar. Excellent news for millions of babies.

But is this desire to act selective? What system does the youngest clientele of Nestlé face in other regions of the world today? This latest investigation by Public Eye focuses on Africa, a key market for the Swiss multinational, where obesity has become a major public health concern.

Promoted as “specially designed to meet the nutritional needs” of babies, Cerelac infant cereals are the most popular on the African continent. Annual sales exceed USD 250 million and Nestlé has a market share of over 50%, according to exclusive data obtained from Euromonitor, a company specialising in the food industry.

On the trail of sugar

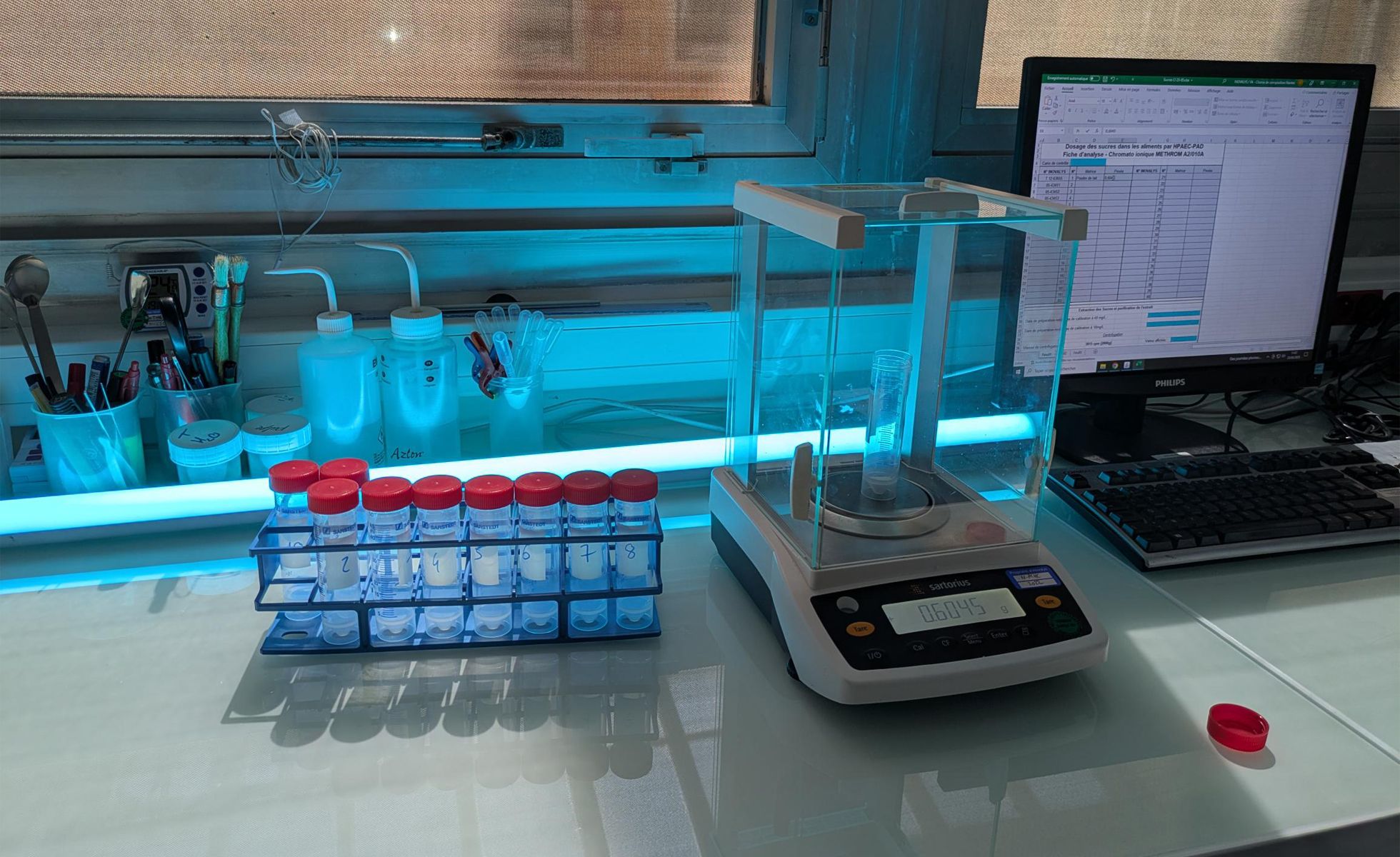

With the help of various civil society organizations in Africa, we collected nearly a hundred Cerelac products sold in 20 countries on the continent and had them analysed by Inovalys, a reference laboratory specialising in the agri-food sector. The result: more than 90% contain added sugar, in high quantities.

In Switzerland, where the company is headquartered, Nestlé’s main baby cereal brand comes with zero added sugar. And in key European markets such as Germany and the United Kingdom, where Nestlé also sells Cerelac baby cereals, all products targeted at babies from six month onwards have no added sugar either.

©

Laurent Gaberell

©

Laurent Gaberell

In light of this unacceptable double standard, civil society organisations from Africa call on Nestlé to comply with World Health Organization (WHO)’s guidelines and immediately stop adding sugar to its baby foods, everywhere in the world.

In an open letter, 20 civil society organisations in Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Togo, Tunisia and Zimbabwe are calling on the food giant to immediately stop adding sugar to its baby foods.

“All babies have an equal right to healthy nutrition - regardless of their nationality or skin colour. All babies are equal. So do the right thing. The world is watching”, they warn.

In 2024, a petition signed by 105,000 people was delivered to the company. But as of today, Nestlé is turning a deaf ear to this appeal.

Up to nearly two sugar cubes

On average, each analysed serving of Cerelac contains nearly six grams of added sugar, around one and half sugar cubes. This is 50% more than the average found in our first investigation, which focused mainly on products sold in Asia and Latin America. And twice the amount detected in India, the main market for Cerelac worldwide.

The highest quantity detected in Africa – 7.5 grams per serving or almost two sugar cubes – was found in a Cerelac product sold in Kenya and intended for six-month-old babies. Overall, Cerelac infant cereals containing at least seven grams of added sugar per serving were listed in seven African countries.

Another revealing fact: With the exception of two variants recently launched in South Africa, all the products with no added sugar that we could find were not intended by Nestlé for the African market but imported from Europe by other actors.

“These practices speak to a long history of colonialism, exploitation and racism”, said Lori Lake, from the University of Cape Town in South Africa, where Public Eye met mothers who use Cerelac in poor rural areas. “It feels like Nestlé is knowingly fueling the fire of obesity and diet-related diseases in Africa.”

Serious public health consequences

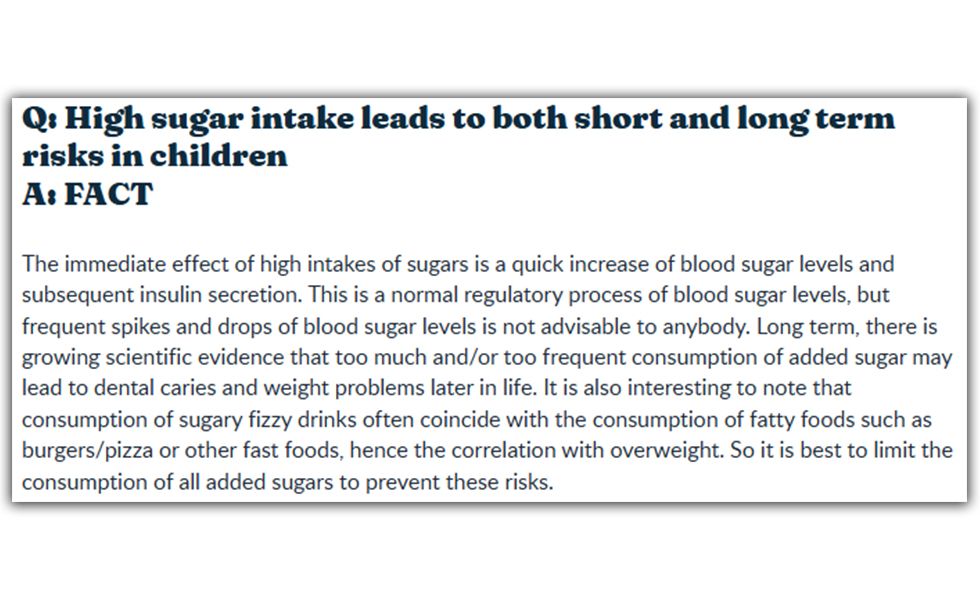

The WHO has warned for decades that early exposure to sugar can create a lasting preference for sugary products and is a major risk factor of overweight and obesity. Obesity is increasing at an alarming rate on the African continent, causing an explosion in diabetes, high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases.

Childhood obesity in Africa is also a rising concern, with the number of overweight children under five nearly doubling since 1990. Most African countries are now facing a “double burden” of malnutrition, where underweight and obesity exist side by side.

Obesity is already imposing significant costs on Africa’s public healthcare systems. If current trends continue, obesity could increase by more than 250% on this continent by 2050, with one in two adults projected to be affected by overweight or obesity.

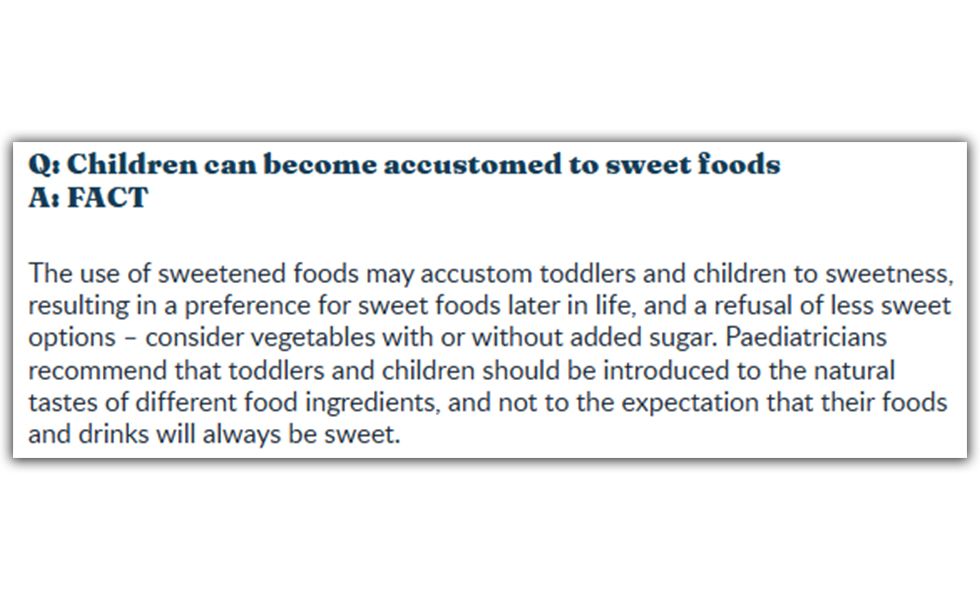

Nestlé is well aware of these risks. “Children can become accustomed to sweet foods” Nestlé writes on a website aimed at South African parents . “High sugar intake leads to short and long terms risks in children”, the company adds. “It is best to limit the consumption of all added sugars to prevent these risks.”

“We do not mislead consumers”

For around two thirds of the products we analyzed, the amount of added sugar was not even disclosed in the nutritional information on the packaging. This lack of transparency “undermines consumer rights and public health”, stated Chiso Ndujkwe-Okafor, Executive Director of the Nigerian Consumer Advocacy and Empowerment Foundation (CADEF). “Parents must be empowered with clear, honest information to make safe choices for their children”

With annual sales of over USD 50 million, Nigeria is the largest market for Cerelac on the African continent. CADEF calls on Nestlé “to align with WHO guidelines” and remove added sugars from all its baby food products.

©

James Oatway / Panos

©

James Oatway / Panos

Contacted by Public Eye, Nestlé emphasised its “consistent approach to nutrition for all babies everywhere”. The company explained that it had accelerated the roll-out of Cerelac with no added sugar worldwide, including in Africa. “By the end of 2025, we aim to have introduced variants of no added sugars to all markets where we operate.”

Nestlé stated that it fully complies with national legislations and that its internal guidelines set a threshold for added sugars that is well below that stipulated by the international standard of the UN Codex Alimentarius Commission. Nestlé added that it declares sugar content transparently in accordance with local regulatory requirements. “We do not mislead consumers.”

“Marketing hidden as compassion”

However, Nestlé aggressively promotes Cerelac as “specially designed” to meet the nutritional needs of babies, offering “an optimal level” of vitamins and minerals for their proper growth and development. And the company targets parents on social media and other online channels in ways that are often not recognizable as advertising.

Nestlé targets also health workers, for instance through the Nestlé Nutrition Institute. It uses this platform, whose stated objective is to “share leading science-based information and education with healthcare professionals, scientists and nutrition communities”, to polish its image and extend its influence.

“We see incredibly high rates of Nestlé marketing, and it’s often hidden as compassion”, said Petronell Kruger from the Healthy Living Alliance (HEALA), a coalition of civil society organizations in South Africa. “As a result, Cerelac is for most people a healthy and almost pharmaceutical product.”

Kruger is outraged by Nestlé’s “blatant racist decision-making to feed lower-income countries with poorer quality food”. Her message for the Swiss multinational company: “Treat African babies like you would treat children in your own family.”

“Fight malnutrition”

Nestlé does not hesitate to assert that its Cerelac products, which are fortified with vitamins and minerals, are key to “help fight malnutrition”, especially across Africa, where “millions of children are impacted by micronutrient deficiencies”.

In Ivory Coast, the consumers association (AIC) condemns this “misleading marketing” by Nestlé, which “endangers the health of the youngest children”. It is “outraged” by the fact that Cerelac products sold in Ivory Coast contain more than 6 grams of added sugar per serving, while such products have no added sugar in Europe.

©

James Oatway / Panos

©

James Oatway / Panos

Sara Jewett, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, is also not convinced by Nestlé’s marketing arguments: "While fortification should remain part of a public health response to malnutrition, we need to look at products as a whole to determine their social value.”

“When the fortification is combined with addictive and harmful sugars, the balance does not seem right.” For her, the findings highlighted by Public Eye “reflect a continuation of Nestle's long history of corporate disregard for the health of infants in Africa in the pursuit of profit.”