Nestlé’s sweet lies

Géraldine Viret, December 16, 2025

“All babies have an equal right to healthy nutrition - regardless of their nationality or skin colour. All babies are equal.” With these strong words, 20 civil-society organizations from 13 African countries addressed Nestlé’s new CEO, Philipp Navratil.

In an open letter dated 17 November 2025, they demand that the multinational end the double standard exposed by Public Eye’s investigation: in Africa, Nestlé’s infant cereals contain high levels of added sugar, while in Switzerland and in the main European markets, such products are sugar-free. “Do the right thing. Not tomorrow. Not next year. Today! The world is watching,” they conclude.

A Nestlé scandal shakes Africa

From the British daily The Guardian to the news agency Reuters and the news network Al Jazeera, our revelations reverberated across global media. “Two different standards for two different worlds,” summed up a journalist from the Indian media outlet Firstpost. And in this “world” where babies’ health seems to matter less to Nestlé, the news spread like wildfire, sparking outrage across the African continent. In Senegal, the Ivory Coast, South Africa and Togo, our partners’ demands were widely echoed in the press: zero added sugar in infant cereals sold in Africa!

In countries such as Nigeria, the biggest market for Cerelac infant cereals on the continent, conferences bringing together journalists, civil-society organizations and regulatory agencies were organized. According to nutrition experts present in Lagos, Public Eye’s investigation has triggered “an important debate across Africa about food safety, corporate ethics and the rights of children to equal nutritional protection,” reported the Nigerian Daily The Sun. For many parents who trust Nestlé, “the revelations have raised questions that regulators and manufacturers may now be pressured to answer more fully,” added the Sun.

Bad faith as a counterattack

Back in Vevey, calls for greater transparency and ethics appear to have fallen on deaf ears. In a response sent to our partners, the food giant denies any “double standard” and loudly proclaims: “We apply the same care to every child, everywhere.”

A quick visit to Nestlé’s promotional site in Switzerland, however, shows that in this country “little tummies” are fed only with products proudly labelled “no added sugars.” Meanwhile in Africa, 90 per cent of products tested by Inovalis – a leading laboratory in the food sector, commissioned by Public Eye – contained added sugar, and in significant quantities. With the exception of two variants recently launched in South Africa, the products with no added sugar that we could find were not intended by Nestlé for the African market but imported from Europe by other organizations.

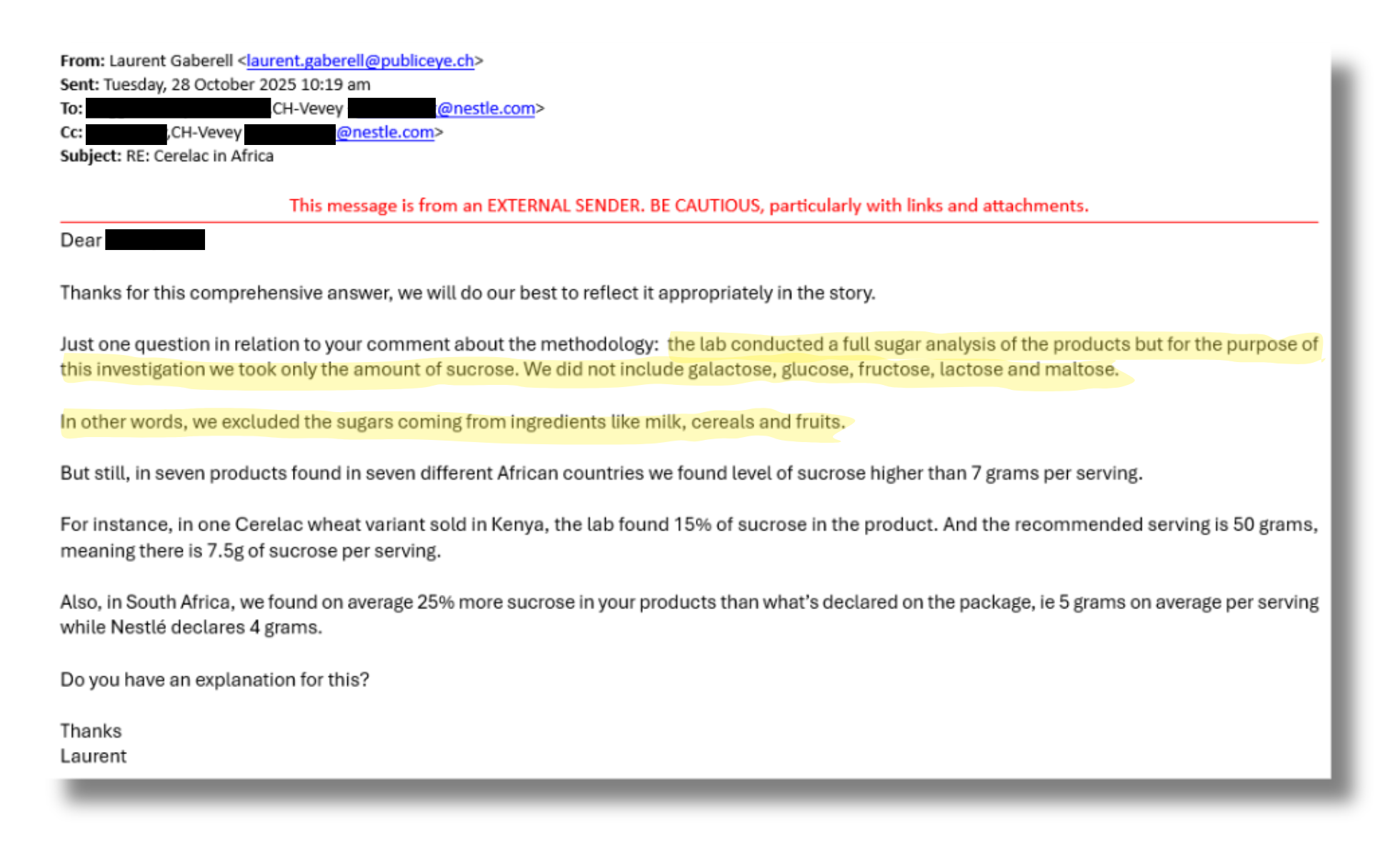

When facts contradict fine-sounding words, Nestlé resorts to a well-worn tactic: shoot the messenger. In the press, a Nestlé representative branded our report as “misleading”, claiming that it is “scientifically inaccurate to refer to the sugars coming from the cereals and naturally present in fruits as refined sugars added to the products.” Yet only sugars added in the form of sucrose and honey were counted in our results; sugars naturally present in cereals, fruits and milk were excluded. Nestlé cannot ignore this information, as we shared it in writing – as shown by this e-mail exchange dated 28 October 2025, three weeks before our investigation was published.

However, since the multinational never shies away from an extra sugar cube – or an extra lie – it went further in the media, falsely claiming that Public Eye “had refused to share details of its testing.”

As for the problems linked to sugar, Nestlé does not address these with any greater honesty. “The biggest challenge in Africa is not obesity: it is malnutrition,” the company told The Guardian, ignoring alarming figures from the World Health Organization, which warns of a “double burden” of malnutrition, combining stunted growth, underweight and obesity within the same populations. The WHO has warned for years that early exposure to sugar can cause a lasting preference for sugary foods and is a major risk factor for obesity.

While the food giant boasts about offering solutions enriched with iron and other nutrients, it does not hesitate – in certain versions of its response – to present sugar as a key ingredient in its fight against malnutrition: “Having cereals sweet enough to be palatable to infants was vital in combating malnutrition.” And it adds: “Remember that children at the age of six months […] can refuse to eat, and if they refuse to eat, they will not be able to grow properly.” Perhaps, unlike Swiss toddlers, African babies are picky eaters with a sweet tooth?

Nestlé aims to have rolled out variants with no added sugar in all its markets by the end of 2025. But the African organizations that wrote the letter to Nestlé dismiss this as a “half-measure” that is wholly inadequate. “If added sugar is not suitable for Swiss and European children, it is not suitable for children in Africa and beyond,” they insist.

To quote the Swiss satirical newspaper Vigousse: “The world is watching Nestlé, but Nestlé, apparently, couldn’t care less.” For how much longer? Public Eye and its African partners are determined to hold the multinational to account.

Read our investigation:

Read our report in South Africa: