RAM tax Congolese telecommunications scandal: a Belgian business network operating in Kinshasa and Geneva

Agathe Duparc in collaboration with Robert Bachmann, September 10, 2025

At first, the idea appeared to be rather well-meaning: the Congolese government was finally going to bring some order to the growing, but chaotic mobile phone sector. With a population of 105 million, including nearly 60 million current mobile-phone subscribers, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was facing an explosion of counterfeit devices. These phones, sold even in brick-and-mortar stores, were not only unreliable, but often dangerous. Not to mention the frequent theft of devices occurring, giving rise to violence and trafficking.

When he was elected President in December 2018, Félix Tshisekedi promised to turn the page on the era of Joseph Kabila, his predecessor, who had been in power since 2001. As we recounted in the Congo Hold-up investigation, Kabila’s period in office was marked by war in the east of the country, by corruption and financial embezzlement. One of Tshisekedi’s flagship measures was the launch of a national digital plan presented as a “lever for integration, good governance, economic growth and social progress.”

As it was, in September 2020, right in the middle of the COVID crisis, the Minister for Postal Services and Telecommunications, Augustin Kibassa, who happens to be President Tshisekedi’s brother-in-law, announced the creation of a Mobile Device Register (RAM). Adopting this measure, recommended by the International Telecommunication Union, meant that all IMEI numbers (the unique identifier of mobile phones) could be listed, thereby making it possible to block counterfeit or stolen devices.

©

AP Photo/Jerome Delay

©

AP Photo/Jerome Delay

Outcry over the RAM tax

In several neighbouring countries operating similar schemes, mobile-phone registration was free of charge. But the Congolese authorities decided that this register would be paid for by users through an annual RAM tax: 1 US dollar for 2G phones and 7 US dollars for 3G, 4G and 5G devices, which would be automatically charged in six instalments by the telephone operators. According to the promises from the government, these revenues would finance “various benefits” helping to reduce the digital divide, such as the construction of telephone assembly plants or the installation of free Wi-Fi in universities and public spaces.

But in a country where 73 percent of the population live on less than 2.15 US dollars a day, this scheme, which also had serious issues, quickly sparked resentment. Those who had two SIM cards on the same phone, a common occurrence in the DRC, were charged double. When it came to the economically most disadvantaged people, their credit top-ups were immediately swallowed up. Some numbers were cut off overnight, even though the government had promised a moratorium, lasting one to two years, on disconnecting counterfeit devices. Consumer protection associations organized demonstrations calling for the fee, which they considered “illegal and anti-social” to be scrapped. Faced with this outcry, the Congolese Parliament also took up the matter, with many MPs calling for the measure to be removed, as considered by some to be “a flagrant scam”.

30 percent of the revenue paid to a discreet service provider

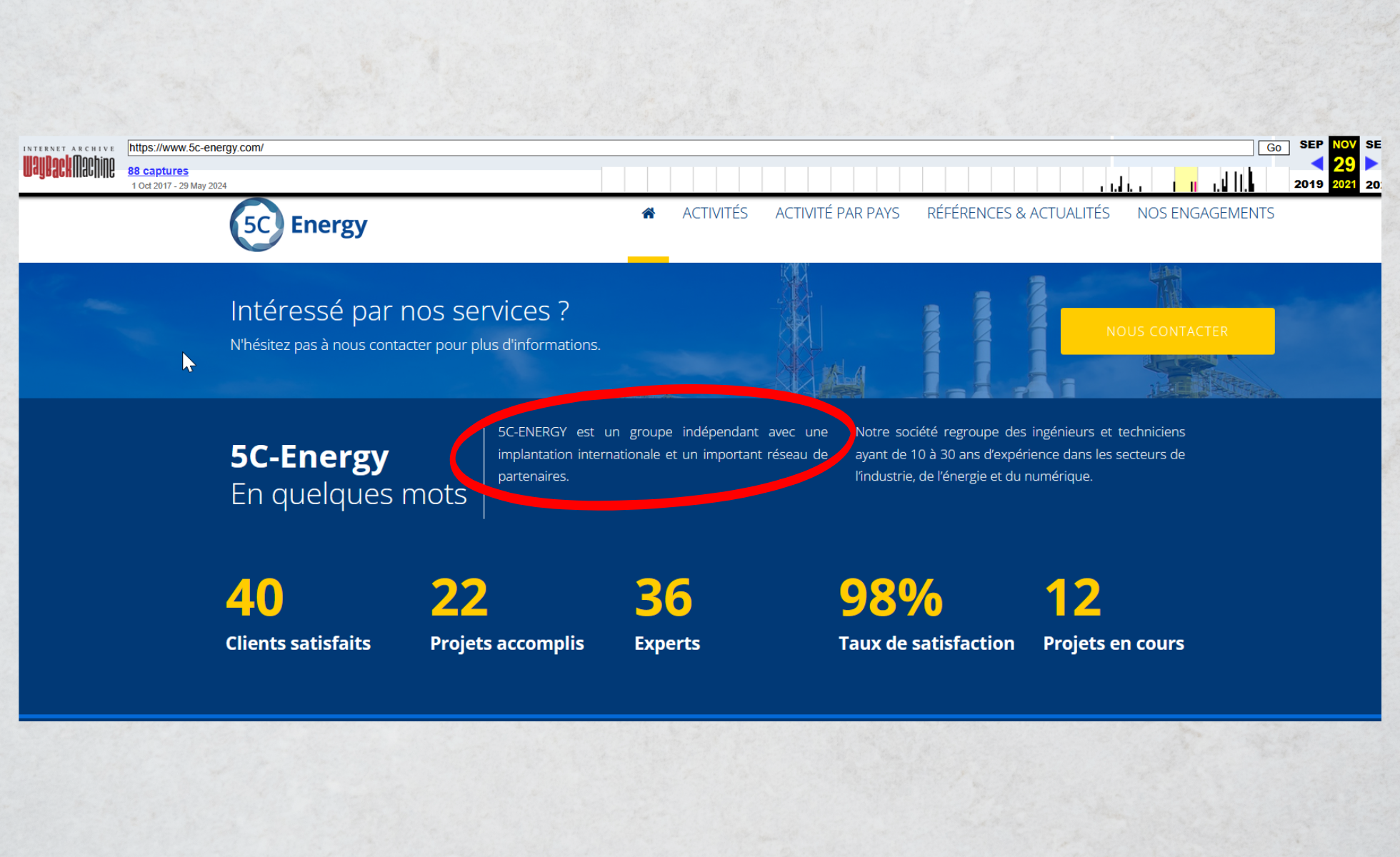

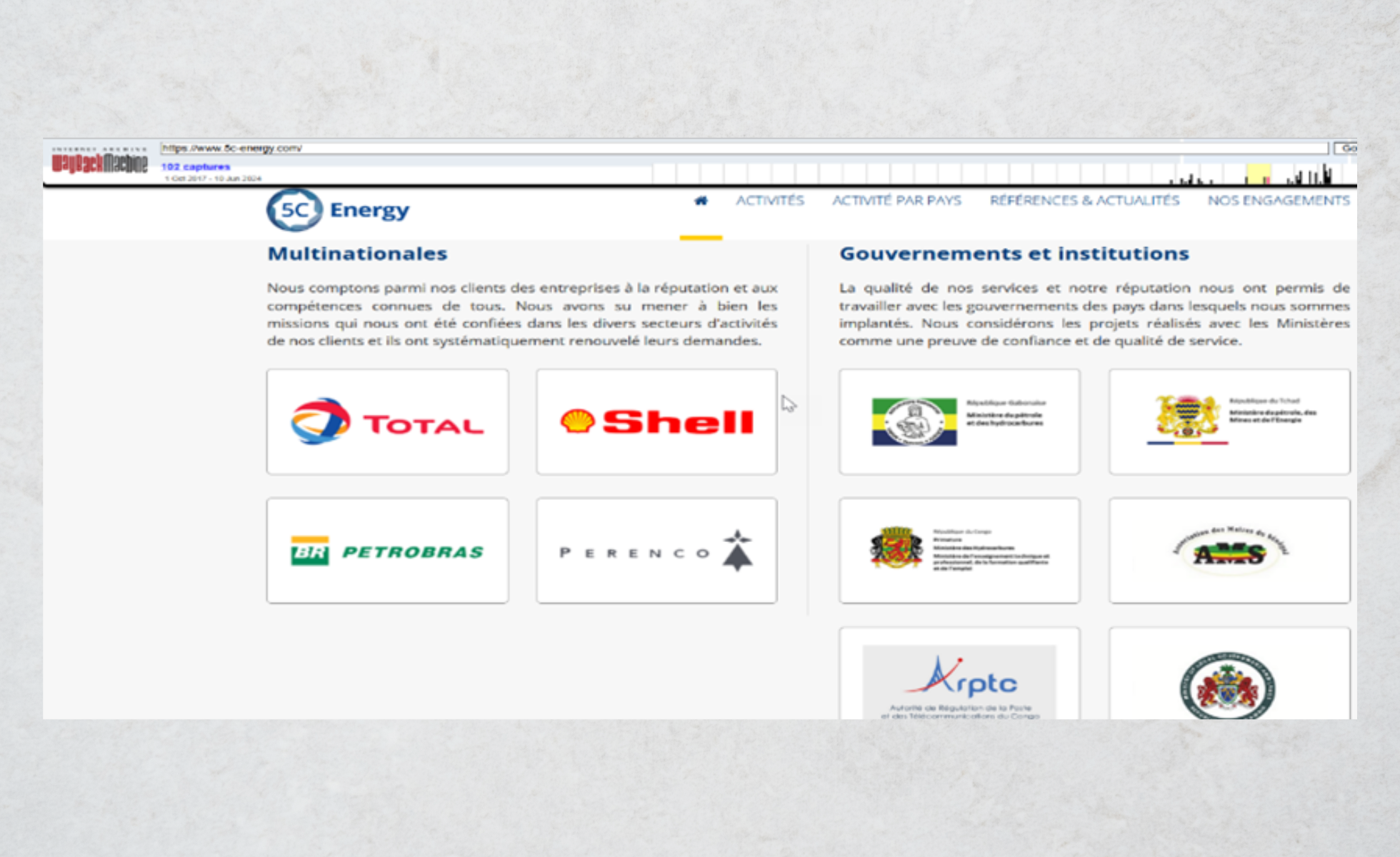

This huge scandal also has a financial side to it. On the eve of launching what the authorities called a “fee”, the Minister for Telecommunications publicly acknowledged that the RAM would be set up with the help of a private company: 5C Energy RDC. The Congolese media revealed that this service provider, with its unknown profile, was part of a group whose main branch – 5C Energy SA – was based in Geneva. According to the president of the ARPTC (the Congolese Authority for the Regulation of Postal Services and Telecommunications) – the body in charge of implementing the RAM and whose leadership is appointed directly by the Congolese presidency – this company was chosen for its “references for a whole series of projects in Africa”. The company’s mission was “to support the implementation of the RAM for five years” and provide “technical support”. In return for this, it was expected to receive no less than 30 percent of the revenues generated by the RAM tax, with the remainder going to the Congolese state, he explained.

This lucrative deal quickly became the focus of everyone’s suspicions. Instead of resorting to a call-for-tenders procedure, which allows private service providers to compete according to transparent and fair rules, the ARPTC opted for a contract by mutual agreement with 5C Energy RDC. To our knowledge, this contract has never been made public.

At the time, 5C Energy presented itself on its website – now closed down but accessible in the web archives – as an “independent group with an international presence and large network of partners”, and a provider of “innovative solutions in the digital, industrial and energy sectors”. In 2021, the group had a string of prestigious clients: the oil giants Total, Shell, Petrobras and Perenco, as well as “governments and institutions”. In addition to the reference to the ARPTC, the ministries of petroleum and hydrocarbons in Gabon, Chad and Congo-Brazzaville, as well as the Association of Mayors in Senegal and the Ministry of Lands in The Gambia, were mentioned. We have not found any trace of these partnerships online, apart from a few articles in a Gambian opposition media outlet about the controversial conditions for awarding a tax-collection contract. This contract was reportedly obtained without any tendering process in 2020 by 5C Energy Company Gambia and is under investigation by a local government commission.

On this web page, the “contact” link is no longer accessible, but in a later, redesigned version, 5C Energy gives an address, e-mail address and a telephone number in Geneva as its only contact details. A company of the same name, 5C Energy SA, is domiciled at this address.

When contacted about their alleged business ties with 5C Energy, the oil companies did not respond to our questions.

Origins on the shores of Lake Geneva

5C Energy SA, was set up in March 2016 and registered in Geneva by a chartered accountant who then held its capital in a fiduciary capacity, i.e. on behalf of a third party. At its address, in a beautiful building in the heart of the old town, there is also the office of a well-known lawyer. Eight years later, as the fuss about the RAM tax had died down in the DRC, the lawyer agreed to offer his office as domicile to 5C Energy SA, renamed Veltio Solutions SA, as well as to several other entities indirectly linked to the latter.

When it was set up, the purpose of 5C Energy SA was to “purchase and sell all equipment, for technical installations, oil and gas, as well as carry out any consulting activity relating to this type of project”. Its directors were Belgian businessmen, who were also actively involved in the diamond trade.

The documents seen by Public Eye indicated that the Geneva-based company was linked to the Congolese company. The articles of association of 5C Energy RDC were filed on 1st November 2019 by one of the Belgian citizens who were directors of 5C Energy SA in Geneva, Jérôme Spaey. Twenty days later, another Belgian, Philippe Heilmann, joined the Congolese entity, with part of the capital being sold by Jérôme Spaey.

In July 2020 – two months before the official launch of the RAM tax – 5C Energy SA amended its articles of association. The new company purpose now included a wide range of services related to information technology: “digitalization, mobile solutions for financial services, digitization, blockchains, communication, value-added services, support, as well as any consulting and solution-development activity relating to this type of project.” This change of direction suggests that the Geneva-based company may have been instrumental in obtaining the lucrative Congolese contract.

Deliberate vagueness about the tens of millions raised

For more than two years, the RAM tax and the questions surrounding 5C Energy made headlines in the Congolese media, resulting in a considerable number of publications, debates and arguments. Faced with all the protests, President Tshisekedi, anxious to preserve his popularity, did a U-turn. In February 2022, the government announced, off its own bat, that RAM-related services would be free of charge, thereby scrapping the compulsory fee. The lid was being closed on this momentous scandal, but a whole series of questions remained unanswered.

So far, no official figure has been established for the total amount of money taken from the population between September 2020 and February 2022. When the scheme was launched, the president of the ARPTC estimated that it would bring in more than 50 million US dollars in annual revenue. A year later, the Minister for Postal Services and Telecommunications, Augustin Kibassa, in a hearing before the National Assembly, stated that it had raised 25 million US dollars since its launch, i.e. half the original amount.

According to the estimates from several MPs, this sum should have reached 106 million US dollars. “This calculation was based on the figures given by Minister Kibassa, i.e. 26.6 million 2G phones and 11.4 million operating with 3G and higher,” recalled Claude Misare, a member of the National Assembly, the lower house of parliament, when contacted by Public Eye.

For its part, the Observatory of Public Expenditure (ODEP), a Congolese NGO, estimated in 2021 that the operation should have brought in nearly 266 million US dollars. The considerable discrepancies in these figures have only fuelled suspicions of a lack of transparency and mismanagement.

Hunt for the collected funds

What is even more astounding is that not a single trace has yet been found in the public accounts of the revenues raised from the RAM tax, which, according to the distribution key were supposed to be 70 percent in favour of the ARPTC – with the remainder allocated to 5C Energy – a fact confirmed by the National Assembly’s Economy and Finance Committee in December 2021. “Your committee regrets to announce that the RAM tax is not accounted for either in the general budget or in the special accounts, even where it cannot be found in the subsidiary budgets. This is how far we have gone and we still haven’t found the RAM tax,” said its president, quoted by the Congolese press.

“This tax was not included either in the inter-ministerial order of 27th November 2020 which set the rates for duties, taxes and fees to be collected at the initiative of the Ministry of Postal Services and Telecommunications and for those collected by the ARPTC,” recalls Valéry Madianga, a former investigator with ODEP, when contacted by Public Eye. “Only a technical analysis might have shown the need for a judicial inquiry. It would probably have concluded that it was a clear-cut case of illicit enrichment,” says the anti-corruption activist, now coordinator of the Centre for Research in Public Finance and Local Development (CREFDL), another NGO.

When summoned to explain himself, Augustin Kibassa finally stated that the revenues collected were not a tax but “a remuneration for the services and benefits provided by the ARPTC”. He suggested that management of these funds should come under the exclusive remit of this body, which is under the authority of the Congolese presidency.

5C Energy contract never made public

Congolese anti-corruption associations, regrouped under the umbrella “Congo is not for Sale” (CNPAV), have called in vain for “full transparency” concerning “the actors and companies involved in implementing and operating this illegal tax”.

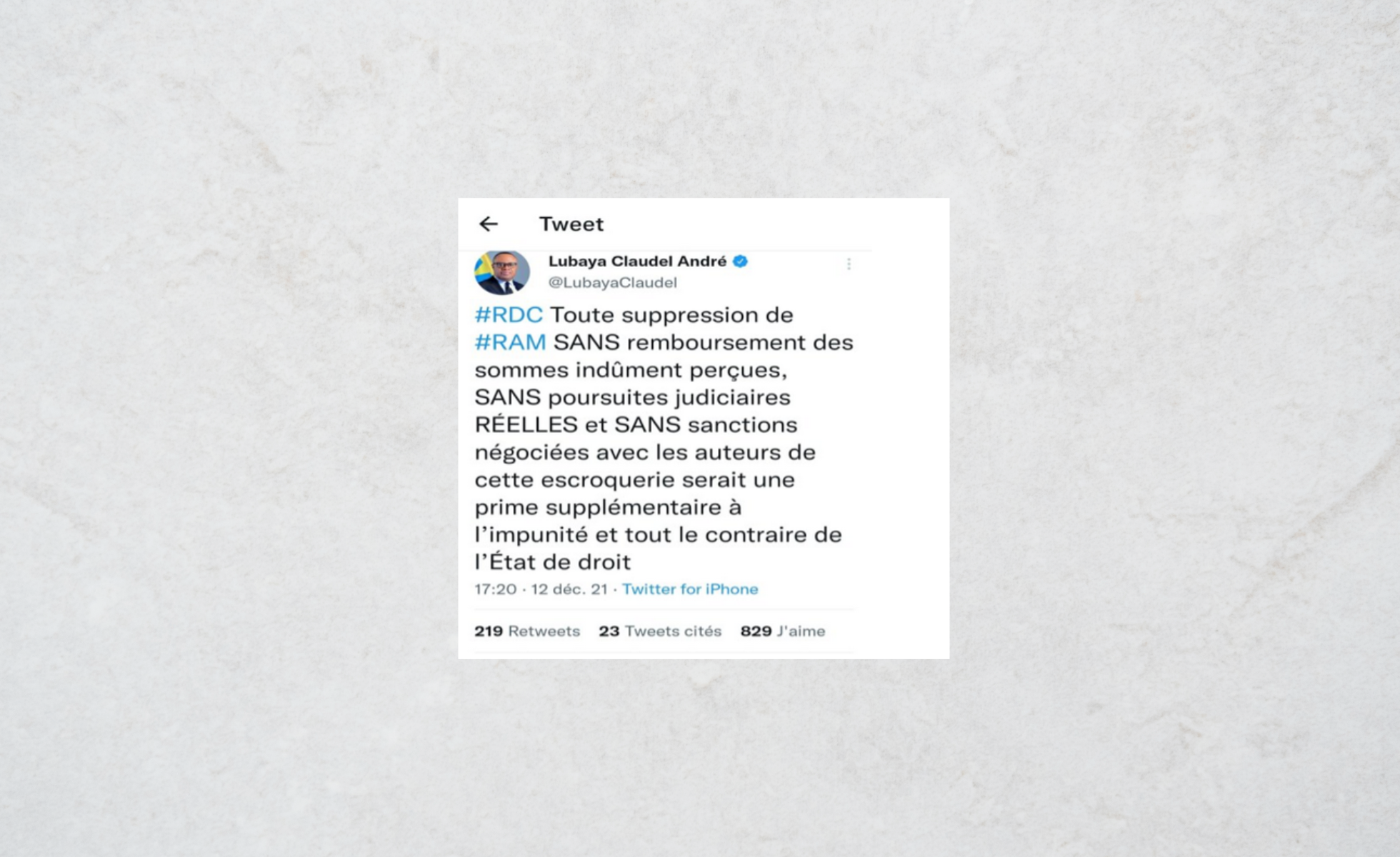

“No-one in the DRC knows how much 5C Energy has invested in equipment and what the deadline is for its amortization, never mind even the terms of the contract. A shroud of vagueness deliberately maintained by this small handful of individuals at the Presidency of the Republic with the intention of bleeding the Republic and robbing the people,” wrote a Congolese media outlet in late 2021, estimating a figure of at least 12 million US dollars for the revenues collected by 5C Energy. Several MPs demanded to receive a copy of the contract between 5C Energy RDC and the ARPTC, but their request came up against a brick wall. “Documents of this nature are kept confidential. Following, I had all kinds of trouble, and a close adviser to President Tshisekedi even threatened me,” MP Claudel Lubaya told Public Eye, showing us the screenshot of this intimidating message. The opposition MP had also called for the “unfairly received” sums to be reimbursed.

This is because the promises to install free Wi-Fi in universities and public places with the money raised from the RAM tax have, according to several testimonies, never been kept. “It only lasted for the time it took for the government to make the announcement,” says Lubaya. We also contacted former MP Juvenal Munubo, who also fought against the tax, who describes it as a “con”. “Wi-Fi is still largely inaccessible to the general public,” he laments.

In a country plagued by corruption – ranked 163rd out of 180 states in Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index – the number of allegations about the alleged support from 5C Energy DRC has increased. Several opposition voices have accused President Tshisekedi and his entourage of profiting from this financial scandal, claims which the latter have strongly rebutted.

“Where did the money go? It’s a state secret,” Hervé Diakese tells us. The Congolese lawyer had filed several lawsuits in 2022 on behalf of consumers, but to no avail.

“I am not a thief and my government isn’t either!” retorted President Félix Tshisekedi, brushing aside the accusations.

The influential Mr H.

As for 5C Energy, it too has emerged from the scandal unscathed, even continuing to expand its influence at the height of it. An investigation conducted by Bloomberg, published last year, reported an episode that allegedly took place in Kinshasa in late 2021. On that particular day, the foreign heads of the four main mobile-phone operators in the DRC were summoned to the presidential residence. They were informed that they would be seeing a significant increase in their tax bill, which caused quite a stir. As the CEOs began to protest, “a white man with dark hair who had been silently sitting in the back of the room broke in to tell them that they’d better comply,” according to the report. This was Philippe Heilmann, the associate of 5C Energy RDC, who the Congolese presidency mandated to accompany the tax rise, which was in fact not implemented in the end.

Philippe Heilmann, a discreet figure, was a director of Dreams of Africa until 2024, a family company specializing in the wholesale trading of diamonds and precious stones founded in 2008. According to Bloomberg, his family co-founded the diamond exchange in Antwerp. The company’s annual accounts, which are available online, show that Dreams of Africa, which had only a handful of employees, saw its profits rocket between 2020 and 2023 from 10,650 Euro to more than 4 million, then falling back to just over 2 million Euro in 2024. The businessman was also actively involved in the property sector via a company he set up in March 2024 in Antwerp. According to Africa Intelligence, he also operates in the security market. An Israeli company tasked with providing President Félix Tshisekedi’s close protection team and training the Republican Guard is said to have won the highly sensitive contract thanks to Heilmann’s support.

Finally, it is interesting to note that Philippe Heilmann’s brother is based in Kinshasa: having worked for Glencore for a long time in Switzerland, he was the company’s commercial director in the DRC between March 2020 and October 2021, according to his LinkedIn account. A letter obtained by Public Eye shows that he was involved in organizing a meeting in November 2020 between Ivan Glasenberg – then CEO of the commodity trading giant – and Congolese President Tshisekedi.

Philippe Heilmann did not respond to repeated requests from Public Eye and did not answer the questions we sent him.

A case of having your cake and eating it too?

Just as discreet, Heilmann’s partner Jérôme Spaey lived in Angola for a long time. He then allegedly headed for the DRC, winning the RAM contract.

In March 2022, after the RAM tax was scrapped, two consortia comprising six companies provisionally won a tender for the renovation of several universities in the DRC. There is one important detail worth mentioning about this: the government had announced that this work, for a total amount of 120 million US dollars, would be partially financed by the revenues raised by the RAM tax.

The Congolese online media outlet Actualite.cd revealed that Jérôme Spaey had indirect links with two of the construction companies (ZS Africa Solutions and SRP Construction) that won the contract and which would therefore have benefited from part of the windfall produced by the RAM tax.

Public Eye has obtained copies of documents shared by the NGO PPLAAF, the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa, which have enabled us to trace this information.

When contacted by Public Eye, Jérôme Spaey sent us the following response: “I am not a shareholder in ZS Africa Solution or SRP Construction, and never have been, either directly or as a trustee. I have never managed either company, either de facto or de jure, and am therefore unable to comment on them.”

More infos

-

A tangled international web of companies

Public Eye was able to trace the indirect links between Jérôme Spaey and the renovation contracts for Congolese universities. The founder and shareholder of SRP Construction (the company tasked with renovating the universities of Mbuji-Mayi and Kananga) is Jérôme Spaey’s partner in a construction company in France. In yet another coincidence, one of the co-founders in the DRC of ZS Africa Solutions (the company authorized to carry out the work in Kinshasa on the National Pedagogical University and the National Institute of Building and Public Works, as well as the University of Bunia) is an Israeli citizen, a shareholder alongside Jérôme Spaey in a construction company based in Slovakia. A few years ago, the ZS Africa Solutions website mentioned among its “achievements” work carried out in Luanda between 2010 and 2015 by the company Jedastruct LDA. This reference has since been deleted. However, Jérôme Spaey is a director of a company in Hungary that bears the same name. There is yet another company called Jedastruct, whose articles of association were filed in the DRC in February 2020, according to documents seen by Public Eye. Its two associates are Jérôme Spaey and his partner Philippe Heilmann.

Epilogue: the Geneva-based lawyer playing host at the end of the process

This is a story of a tax levied on the Congolese population, which allegedly generated millions of dollars, but which never appeared in any official accounts or were never traced in the national budget. Of a small Congolese company, part of a Geneva-based group, which won a “technical support” in a completely non-transparent process in exchange for 30 percent of the revenues. And of a group of Belgian businessmen who juggled with companies and seemingly gained access to the uppermost circles of Congolese power, following a tradition that is unfortunately well established in the DRC. Not to mention valuable connections with Switzerland.

After all, the story of the RAM scandal would not be complete without mentioning the role played by the booming Swiss consultancy sector. We are talking about professionals who provide bespoke financial and legal services and advice, but who, unlike financial intermediaries, are still not subject to Switzerland’s Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA). Therefore, there is no requirement for them to perform KYC due diligence (identification, clarification and understanding of the client’s activities) or to report any potential suspicions they might have of money laundering.

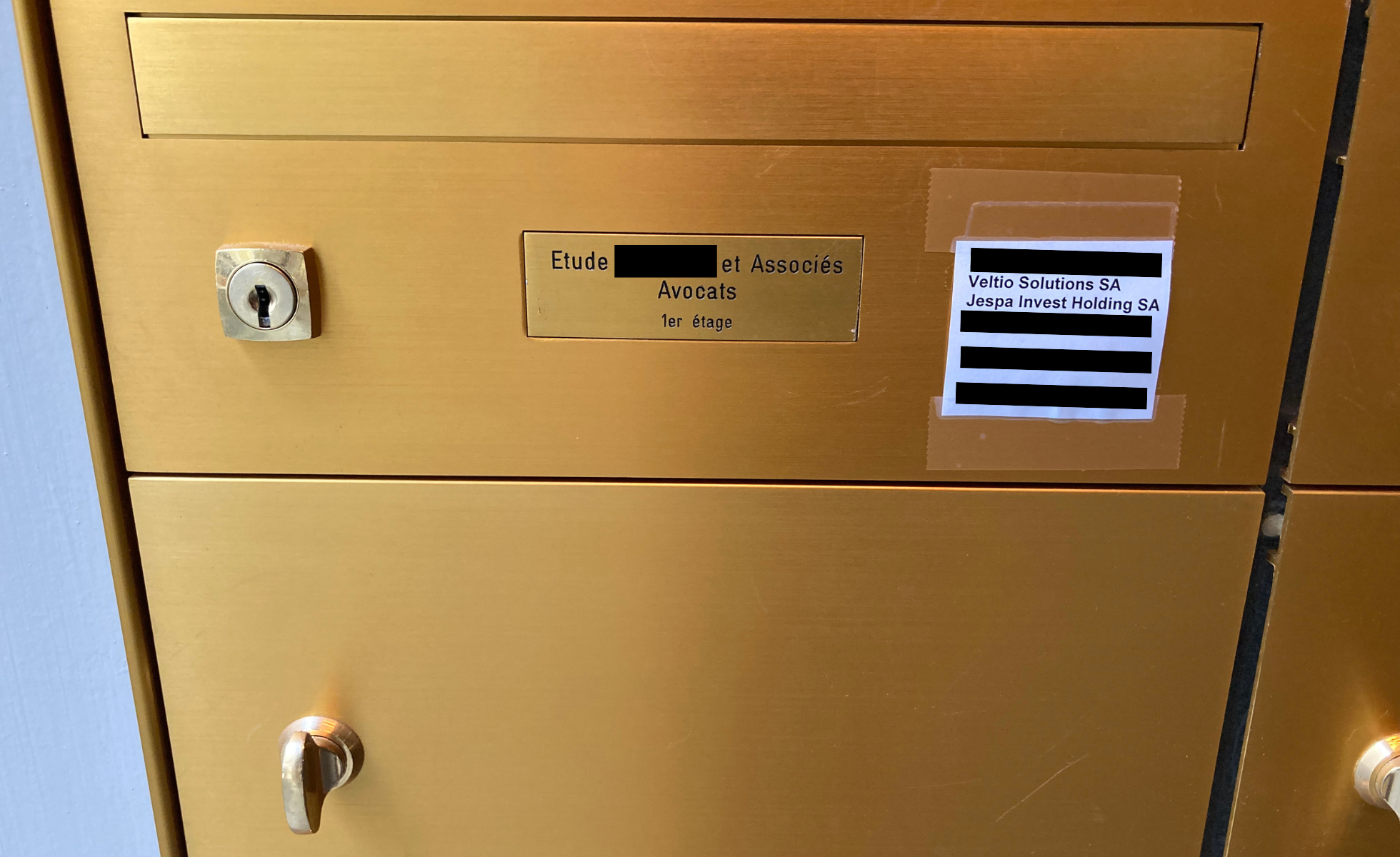

Since it was established in Geneva in 2016, 5C Energy has benefited from this type of service: firstly, when registered by a fiduciary, then domiciled with a lawyer at the end of the process. We discovered that in October 2024, despite the uproar caused in the DRC by the RAM tax, a leading member of the Geneva bar had agreed to host in his office Veltio Solutions SA – the new name of 5C Energy SA since March 2023 – and Jespa Invest Holding SA, a shareholder entity of Veltio whose name is a contraction of Jérôme Spaey. “Providing domicile for a company is an important legal service. It involves more than just providing the customer with a mailbox; they also have to read any correspondence received and respond to it, if necessary,” explains a lawyer who is familiar with this type of practice.

©

Public Eye

©

Public Eye

In this specific instance, this hosting service was to last only a few months, just enough time to close up shop. Jérôme Spaey, whose adventures in the DRC have been widely publicized in the media and who is now resident in Dubai, has distanced himself from the whole thing. He resigned from Veltio Solutions SA in February 2024, with his effective removal from office in November of the same year. In February 2025, the company was dissolved and put into liquidation. Jespa Invest Holding SA remains domiciled at the lawyer’s office. When contacted by Public Eye, the lawyer acknowledged receipt of our questions but did not respond.

We sent around fifteen questions to current and former signatories of 5C Energy SA/Veltio Solutions SA. Its liquidator replied on their behalf that “5C Energy SA, based in Geneva, has never operated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and has not received any remuneration in connection with the contract obtained by 5C Energy RDC in that country” adding that she is “neither able nor authorised to answer questions concerning another company based in another country”. She further added that “Jespa Invest Holding SA (...) as its name suggests, has never had any operational activities of any kind anywhere in the world, it being specified that it has never owned 5C Energy RDC, nor any other company based in Africa.” For his part, Jérôme Spaey replied that “with regard to the activities of 5C Energy RDC, I note that your questions are largely based on accusations already made publicly in Congo, which are completely unfounded,” repeating that “5C Energy SA has never operated within the framework of the RAM and has therefore never been remunerated in this context.”

©

Simon Toupet/Mediapart with AFP

©

Simon Toupet/Mediapart with AFP

Read our research Congo Hold-up.