Payment transparency disclosure Ghana’s national oil company shows the U.K. and Switzerland how transparency should work

Anne Fishman (Public Eye), Alexander Malden (NRGI) & Joseph Williams (NRGI), February 12, 2021

This was demonstrated in NRGI’s recent report Ghana’s Oil Sales: Using Commodity Trading Data for Accountability. Why does this matter?

Ghana shows how data disclosure can improve understanding in this often opaque and economically significant sector.

Disclosure helps oversight actors, such as civil society groups, demand improved accountability, and highlights the role of overseas jurisdictions from which commodity traders operate.

Heavy hitters: Switzerland and the U.K.

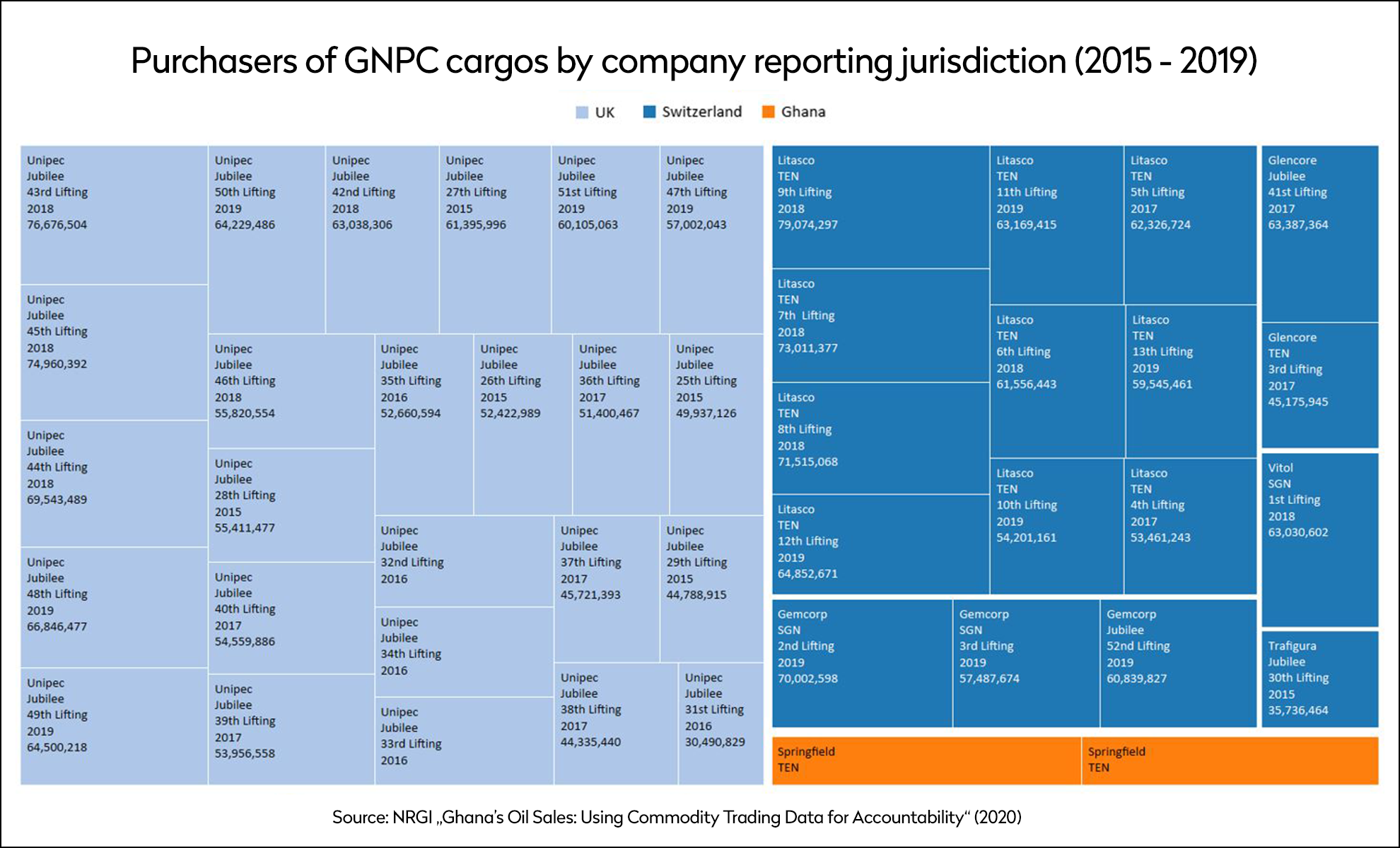

GNPC is responsible for all oil marketing activities on behalf of the Ghanaian state. GNPC’s disclosures show that from 2015 to 2019, it sold 44 cargos to seven different buyers. Of these 44 cargos, 42 were purchased by traders or companies with trading subsidiaries registered or listed in Switzerland (17) and the U.K. (25), with the remaining two cargos being purchased by Ghanaian producer Springfield Group. The cargos sold by GNPC during this period were worth USD 2.6 billion, with 94% ($2.4 billion) paid by commodity trading firms or their parent companies registered or listed in the U.K. or Switzerland.

GNPC sold the vast majority of cargos during this period through two long-term contracts. One contract is with Litasco, the Switzerland-based marketing and trading arm of Russian international oil company Lukoil. Lukoil is regulated through its listing on the London Stock Exchange. The second contract is with Unipec Asia, a subsidiary of Chinese-owned Sinopec, also listed on the London Stock Exchange. Both of these agreements are connected to resource-backed borrowing. GNPC’s 2017 contract with Litasco, which entitles the trader to purchase four cargos per year of oil from the Ghana’s offshore TEN field, was tied to $279 million in bank guarantees. The second agreement, signed in 2012, obliges the state oil company to sell five cargos per year to Chinese state-owned Unipec Asia, forming part of the Ghanaian government’s $3 billion loan from China Development Bank.

During this period GNPC also sold seven cargos through one-off spot sales to four other Swiss traders: Gemcorp Commodities Trading (three cargos), Glencore (two cargoes), Trafigura (one cargo) and Vitol (one cargo).

©

NRGI

©

NRGI

Disclosure is not just the seller’s responsibility

Oil sales disclosure is crucial, and Ghana should not remain the exception in this regard. While a number of other oil-producing countries, such as the Republic of Congo and Cameroon, and their national oil companies (NOCs) have taken steps to improve disclosure, full openness of oil sales by NOCs may not come about in the near term. Traders therefore have a critical role to play in providing transparency on their purchases. Indeed all trading companies buying oil, gas and minerals from governments should disclose their purchases from governments and NOCs in line with the 2019 EITI Standard and granular application of the EITI’s new reporting guidelines for buying companies.

The need for transparency is reinforced both by the current coronavirus crisis and the ever-present corruption risks in the commodity trading sector:

- Debt sustainability. The coronavirus crisis has created massive new governmental spending needs, with many countries including Ghana facing rising levels of debt. Thus, the importance of disclosure is further reinforced when traders purchase commodities from resource-rich countries in the form of resource-backed loans. Because countries entering these arrangements with traders typically receive loans in exchange for the future provision of their oil or other natural resources, such loans carry increased debt sustainability risks for producer countries. Considering the fragile fiscal position of many countries as well as the fall in oil prices, disclosures are required to enable public scrutiny and debate by citizens on their governments resource-backed borrowing activities.

- Commodity trader corruption risks. Last year closed with a raft of corruption indictments against commodity trading firms (including the Vitol U.S. Deferred Prosecution Agreement). In December 2020, Vitol agreed to pay over $160 million to settle charges including those of bribery and corruption to regulators worldwide. The bribery scheme in Ecuador and Mexico was ongoing as recently as July 2020. At the end of November 2020, the Brazilian Federal Ministry announced an investigation of Trafigura (and former Trafigura executives) for suspicious transactions as part of the Lava Jato case. These cases show all too clearly that corrupt and opaque practices are not relegated to the past.

The need for improved disclosure of commodity purchases is clear. Authorities in countries where traders are based, including the Federal Council in Switzerland and Treasury and Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) in the U.K., should require disclosure by these companies. This would help entrench transparency and accountability in the world of commodity trading, in turn benefitting resource-rich countries and ensuring their citizens can hold their government and companies accountable.

Mandatory payment transparency disclosure: what are Switzerland and the U.K. waiting for?

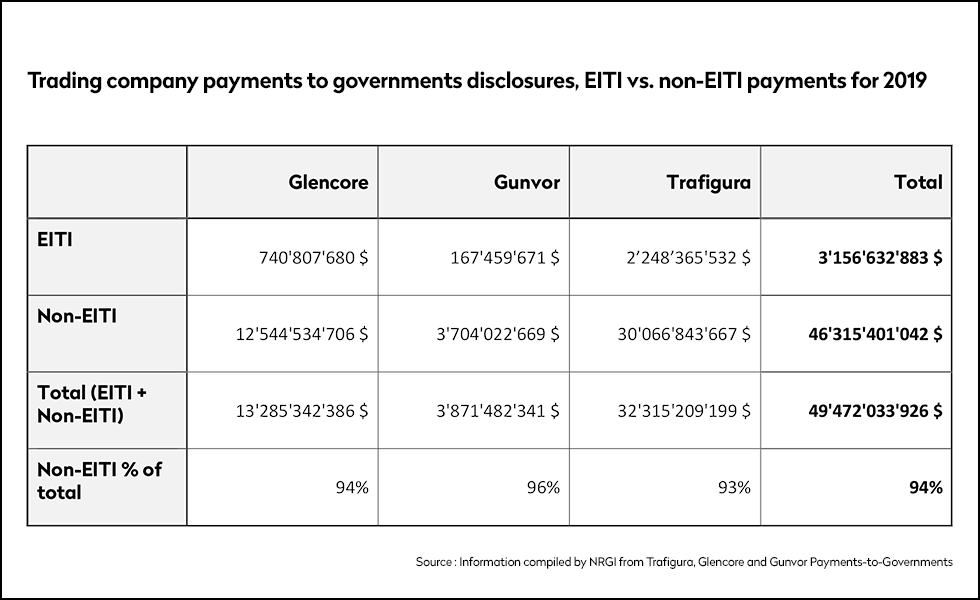

Currently only three companies - Trafigura, Glencore and Gunvor - voluntarily disclose their payments to governments for the purchase of commodities in EITI implementing countries. While these disclosures are a positive development, their refusal to disclose payments made to governments of non-EITI countries results in a limited picture: 94% of Trafigura, Glencore and Gunvor’s combined payments to governments for oil and gas were paid to non-EITI countries in 2019, and were therefore undisclosed beyond global aggregate figures.

Many large U.K. or Switzerland-based oil traders such as Vitol and the trading divisions of international oil companies like BP and Shell are yet to disclose any information of this type, at all. Legislators should compel them to do so.

Governments of trading hub countries should require trading companies buying oil, gas and minerals from governments to publicly report these sizeable payments. Such legislation in key trading hubs such as Switzerland and the U.K. would also ensure that companies disclose payments to all jurisdictions and in a detailed manner, and not just those related to EITI countries. Other hubs such as the Netherlands, Singapore and the United States should act too.

Switzerland passed a law last year which would entitle the Federal Council to include commodity trading-related payments in the legal disclosure requirements now in place for conventional extractive firms in Switzerland. But this provision is only triggered if authorities in other international hubs choose a similar path.

In 2019, the U.K. government committed to “establish and implement a common global reporting standard” in this area, noting that “the largest payment stream missing from mandatory disclosure is payments to governments for the sale of publicly owned oil, gas and minerals (commodity trading), an area where corruption risk is acute.” But as yet, that intention remains unlegislated. Mandatory disclosure laws in Canada, EU, Norway and UK require conventional extractive companies to disclose their payments to governments for their extractive activities, where possible disaggregated to the project-level.

In the words of the OECD Development Centre, the U.K. and Switzerland as main trading hubs have “an opportunity (…) to demonstrate leadership by playing a larger role in countering corruption and enhancing transparency in commodity trading”.

One wonders then: as countries like Ghana are showing the value of information about commodity purchases by traders, what are the Swiss and the Brits waiting for?

Author notes

Anne Fishman is a Policy Analyst in Commodities & Finance at Public Eye.

Alexander Malden is a Governance Officer at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Joseph Williams is the Advocacy Manager at NRGI.

This commentary also appears on the website of NRGI.