Research When Gunvor and Vitol rub shoulders with the same “straw man”

Adrià Budry Carbó and Agathe Duparc, October 19, 2020

Cigarettes dangling from the edge of their mouths, a handful of sixty-somethings gloomily ply their trade all the way down the street. There is nothing particularly remarkable about the premises of this small kosher restaurant, located in the quartier of Strasbourg-Saint Denis, in central Paris. Its website nonetheless promises “excellent food in a convivial atmosphere”, as well as a takeaway service.

Amidst the flurry of motorcycle delivery drivers, the boss is having trouble explaining the items on his menu to the keen visitors on that day. It’s worth pointing out that E.E. is not particularly well-known for his couscous or his Pkaïla; it’s another type of activity that led him to spend five and a half months behind bars, initially in Serbia and later at a prison in Bern, Switzerland.

“How did you find me?” asks E.E., a tired-looking man in his fifties whose physique doesn’t fit the typical image of someone who deals in international finance. Formerly a textiles and furniture dealer, and now a fast-food restaurant owner, this French-Israeli has inadvertently become a protagonist in the complex and sprawling Gunvor case. This corruption scandal involving oil contracts in Congo-Brazzaville and Côte d’Ivoire, which Public Eye has previously investigated, resulted, in October 2019, in the unprecedented conviction of the Geneva-based trading company for “organisational failures”. As part of this conviction, Gunvor was ordered to pay CHF 94 million, including a fine of CHF 4 million and CHF 90 million in compensation amount (créance compensatrice).

In another, less public case, E.E. was also given a criminal conviction by the Swiss courts in September 2019. As part of Simplified Proceedings, he admitted having served as the front man on behalf of Zilan HK Ltd. In 2012, this shell company, which held its bank accounts at the Latvian bank Rietumu, had been at the receiving end of a chain of commissions paid by Gunvor, to the value of EUR 300,000 and USD 450,000, to obtain shipments of crude oil from Congolese leaders. The funds had first transited through SEF (FINANCE) SA Suisse, a Swiss asset management company, then through Hong Kong via another company managed by E.E.’s accomplice David Jonathan Benouaich, a French citizen who is still on the run and subject to an international arrest warrant.

Textiles and forgery

E.E. states that he was swindled by his former partner, who he had known since 2007, and to whom he had agreed to lend his name and signature. He says that he knows nothing of the recent wanderings of David Benouaich, a man towards whom E.E. harbours somewhat bitter sentiments. “They ruined my life,” he lashes out, without specifying who “they” are. “I was in the wrong place at the wrong time.” This was rather unsatisfactory for the Swiss courts, which sentenced him to 14 months in prison, including a nine-month suspended sentence, for “document forgery”.

The Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland initially had wide ambitions on this case, suspecting E.E. and Benouaich of working together as “members of a network of professional money-launderers” operating out of various offshore companies.

The Swiss investigators identified at least five suspicious companies, of which two (Universal Trade Business Ltd and Gollum West Ltd) held their accounts in Geneva at the Bank of China (Switzerland), an institution that was later swallowed up by Julius Baer bank. Their analysis reveals a “multitude of ‘in/out’ transactions worth several million dollars”, justified by textiles sale and purchase operations, or in other words suspicious transactions in which money lands in one account only to be swiftly transferred to another.

According to the indictment seen by Public Eye, E.E. admitted having deceived his bank managers in Geneva by falsely designating himself as the beneficial owner of those funds. On 20 September 2019, he was found guilty by the Federal Criminal Court in Bellinzona.

The middleman played dumb, claiming to have never seen or heard of all these six- or seven-figure deposits and withdrawals. The furthest he went was to admit that these were “transit accounts for the transfer of funds received from and destined for third-party natural and legal persons, and that the funds allegedly being paid into the accounts in question did not belong to him.” The Office of the Attorney General, unable to prove the criminal origin of the money, was forced to drop the charge of money-laundering (art. 305 bis of the Criminal Code) that it had initially brought against him.

E.E. managed to get away with a minimum conviction and the case was closed there, without causing a media stir. This was probably to the great relief of certain individuals, who the case must have brought into a cold sweat because, according to our information, Gunvor is not the only big trader to have used the services of this French-Israeli middleman. The story had hitherto remained in the shadows…

©

Karl de Keyzer/Magnum

©

Karl de Keyzer/Magnum

The next round

Our exclusive investigation has found that Vitol too was doing business with one of E.E.’s offshore companies. According to banking documents that we consulted, the oil trading giant made 11 payments to Samariti Shipping Ltd (SSL) between 3 October 2014 and 23 March 2015, amounting to over EUR 3.3 million (then equivalent to 3.5 million francs). At the time, E.E. was the only beneficial owner and signatory of the company, which held its accounts at HSBC in Hong Kong. The money came from JP Morgan in London. All the more ironic, then, that the legal investigation of Gunvor was already well under way in Switzerland, and the investigators already had the middleman in their sights.

A completely unknown entity in the commodity trading sphere, the small company Samariti Shipping Ltd was incorporated in Hong Kong in February 2013 thanks to the services of a French lawyer who had formerly served as foreign trade advisor for France in the Chinese city-State. SSL claims to deal in the maritime and river shipping of fabrics, sofas and lamps in China, France, Europe and Africa, in particular Angola, with a reported turnover of EUR 5 million.

The company’s bank account displays a swift series of inflows and outflows of funds, as if it were simply a transit structure. To be more precise, Vitol SA paid over EUR 3.3 million to Samariti Shipping Ltd, then on the same or the following day a total of at least EUR 1.9 million was paid out to various Chinese citizens who held accounts with the Bank of China in Hong Kong.

This modus operandi is reminiscent of the practices used in the Gunvor case. The Office of the Attorney General managed to prove that the EUR 300,000 and USD 450,000 received by Rietumu bank in Riga on behalf of Zilan HK Ltd – the company for which E.E. was the sole signatory – had subsequently been transferred “primarily to Chinese citizens and companies, by banking institutions, in particular in China, which appear to be related to compensation operations,” as can be read in the indictment of the company. The Swiss judicial authorities suspect that these compensation payments enabled a payment to be made to an individual close to the family of Denis Sassou Nguesso, who has ruled the Republic of Congo since 1979 (if one discounts a democratic interlude between 1992 and 1997).

In a video filmed secretly in 2014 and exposed by Public Eye, a former Gunvor senior executive is shown giving details of the schemes that enabled bribes to be paid to Congolese officials.

A coveted but risky market

The major trading companies have rather fraught relationships with Congo-Brazzaville, a market which is highly coveted for both the quality of its crude oil and the rebates offered by the Société nationale des pétroles du Congo (SNPC), while also being high-risk from a compliance perspective.

SNPC, which is regularly strangled by the weight of its repayments for pre-financing (i.e. loans secured on future oil shipments) granted by traders, is subject to audits by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In 2017, one of Public Eye’s sources was already pointing out that, “to avoid drawing attention, it applies roughly the same discounts to all the traders. That’s why they’re falling over themselves to get hold of some Congolese crude oil. Having Congolese crude is like printing money!”

“Having Congolese crude is like printing money!”

-

©

M. Torres/iStock

©

M. Torres/iStock

-

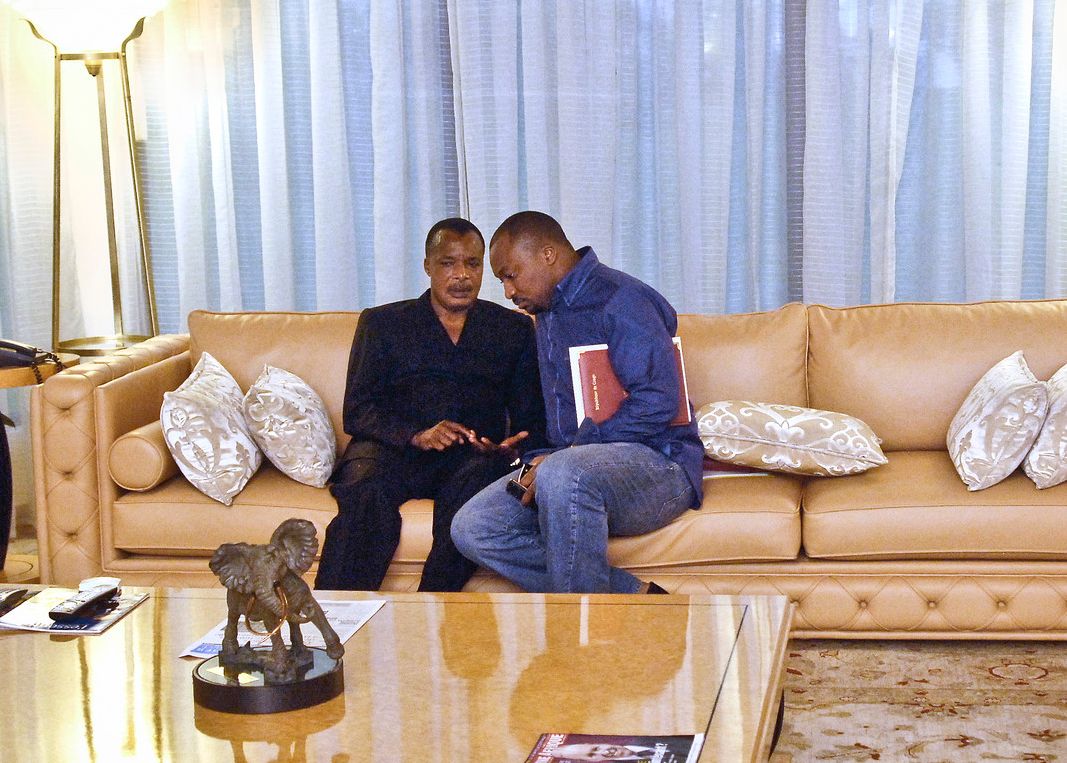

©

Vincent Fournier/Jeune Afrique

©

Vincent Fournier/Jeune Afrique

-

© Pascal Deloche/Godong/Keystone

Unsurprisingly, Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso, the President’s son, is the “deputy director” of SNPC. He is suspected by the US courts of having embezzled millions of dollars between 2011 and 2014, with prosecutors alleging that he accepted USD 1.5 million of kickbacks from oil companies. His name also appears in the French Bien Mal Acquis (“ill-gotten gains”) case, which seeks to establish whether prominent properties acquired by a number of families of African despots, including the Sassou Nguesso family, were bought with misappropriated public funds.

Meanwhile Vitol has been operating in the Republic of the Congo at least since 2005, through its involvement in two offshore oil blocks in the Congo river basin, namely Marine XIV (21.55%) and Marine XI (26,11%), via its subsidiary Raffia Oil. The resale of the licence of the latter, Marine XI, was the subject of quite a battle – documented by Global Witness in its October 2019 report The Spotlight Sharpens – between Vitol and Africa Oil and Gas Corporation (AOGC). Following a confrontation in the UK courts, Vitol continues to demand full compensation for its assets.

So, were the USD 3.3 million paid by Vitol to Samariti Shipping Ltd on the sidelines of an oil deal or oil transaction in Congo-Brazzaville? We cannot be certain.

The middlemen duo fall who serve the Congolese elite

On two occasions when Public Eye has enquired about the nature of Vitol’s relations with the small Hong Kong-based company, Vitol has refused to shed light on “any dealings it may or may not have had with SSL as they would be subject to confidentiality”.

The trading house also states that it “never undertook business with any state entity of Congo-Brazzaville (including SNPC) during the period in question, i.e. 2014 - 2015”. However, it remains silent on the question of possible purchases of oil from private entities, such as from small trading houses that navigate in Sassou Nguesso’s sphere of influence. Most “business relationships are subject to confidentiality constraints”, the Geneva-based trader responds, asserting that “the volumes [traded] by Vitol in Congo-Brazzaville were very low”. They did occur, though. Vitol states that it “conducted no business in Congo-Brazzaville (or any other jurisdiction) as a result of intermediation from SSL or Mr E.E.”.

However, numerous factors testify to the fact that the E.E. – Benouaich duo were well-connected with the Congolese elite. The confessions of a former Gunvor employee, convicted of corruption in August 2018, testify to this. The former employee stated that Cédric Okiorina, marketing director at SNPC and close advisor to Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso, organised to meet him in a Parisian hotel in 2011 “to introduce him to the person who would receive the funds in his name, namely David Jonathan Benouaich, holder of the company ATIS HK Ltd”.

Another fine connoisseur of the matter drives the point home: “For Gunvor, it was clear that Benouaich, and consequently E.E., were completely in bed with the traders in Congo-Brazzaville. Their job was to set up companies, receive money and transfer it. The Congolese trusted them completely and so they were very influential”, he said.

“For Gunvor, it was clear that Benouaich, and consequently E.E., were completely in bed with the traders in Congo-Brazzaville.”

E.E., who seems to have retreated in his restaurant business, states that he had vaguely heard of Vitol “in the press”. He claims to have never travelled to Congo-Brazzaville or met anyone at the national oil company SNPC.

Confrontation at the Office of the Attorney General in Switzerland

It seems odd that Vitol would not have been aware of the dubious reputation of the Franco-Israeli middleman. In April 2014, one of its employees – hired by Vitol’s Africa department in February 2013 as a “business developer” – was summoned by the Office of the Attorney General as “a person called to give information” in the context of the Gunvor investigation. The investigators asked him to provide explanations about a compensation operation that was carried out in January 2011 with… Gollum West Ltd.

This company is based in the British Virgin Islands and run by David Jonathan Benouaich, although E.E. is officially the beneficial owner. The future Vitol employee, who at the time was working as an independent oil consultant / expert for Petrochina and Socar Trading, had transferred EUR 100,000 in cash to a contact in Paris. In exchange, a few days later he received the same amount on his account at Lombard Odier bank in Geneva, from Gollum West Ltd. The justification for the payment given on the invoice was “commission fees for the delivery of a shipment in 2010”. The transfer led his bank account to be temporarily blocked as part of the investigation into Gunvor.

The Office of the Attorney General did not get to the bottom of the case of this suspicious operation, but the case continued to pique the investigators’ curiosity. In May 2015, a confrontation was organised between the Vitol employee and E.E., who had just been extradited from Belgrade. The two men claimed they did not know each other. An amusing situation, considering that the company had just made its final payment – of EUR 483,600 – to Samariti Shipping Ltd, whose beneficial owner is none other than the Franco-Israeli middleman standing in front of him. Payments that the Swiss judiciary is at the time unaware of.

Questioned on this point by Public Eye, Vitol indicated that “it is incorrect to state that [its employee] has acted as an intermediary between Mr E.E.’s network and Vitol and it would therefore be wrong to state, suggest, or infer that is the case”.

Vitol and the textile merchant

Nevertheless, everything in this case seems like a feat of acrobatics. Starting with the chronology. Vitol’s payments started on 3 October 2014, yet an international arrest warrant was issued against Samariti Shipping Ltd’s beneficial owner on 24 July 2014. The information clearly had not reached the ears of the trading house. Or it had not been taken into account – the payments continued at regular intervals until 23 March 2015.

This date marks the end of the adventure, because – out of the blue – three days later on 26 March 2015, E.E. was arrested in Belgrade, Serbia, where he had travelled to purchase furniture. Extradited to Switzerland in May 2015, he spent two more months in detention, which made him request Simplified Proceedings to the Office of the Attorney General.

Should the dubious profile of the Franco-Israeli merchant not have raised numerous red flags within the compliance department? Vitol did not wish to answer this question.

©

Anthony Wallace/AFP/Getty Images

©

Anthony Wallace/AFP/Getty Images

Reporting in Hong Kong

HSBC Hong Kong was more responsive. In January 2015, following numerous transactions considered to be highly suspicious, the compliance department made a Suspicious Transaction Report (STR) on the activities of Samariti Shipping Ltd. Although the transactions do not relate to payments to Vitol, the bank reveals, for information purposes, that a small company claiming to be active in the textile and furniture business, received several millions of dollars from Vitol SA. An internal investigation is launched and, in May 2016, the bank decided to close the account.

E.E. claims he was never aware of these red flags. He claims to have never received the account documentation even though it was in his name. Embarrassed by our questions, he subsequently arranges a phone call with his Parisian lawyer.

Déborah Gignoli Roilette, his lawyer, claims to have no knowledge of Vitol SA. She describes her client as “not very vigilant” when it comes to the use of his name or signature. “Risks have been taken, that is the problem.” David Jonathan Benouaich told him “open your accounts, don’t worry about the rest. But he wasn’t the one who managed them – the perfect straw man”.

The lawyer claimed to be “shocked” by the way the affair unfolded in Switzerland, reflecting the impunity that financial institutions benefit from. “Bank of China accepted to open the account without asking any questions. It saw all the transactions, the justifications of transfer requests. And in the end, they are the ones playing the victim?”

From the terrace of his Parisian restaurant, E.E. patiently waits for the bad memories of his stay in Switzerland to go away with time. For his part, his former partner David Jonathan Benouaich, who probably knows a great deal about the internal scheming of the large traders, is still on the run.

Disclaimer: This version is a translation of a text which was written in French. In case of discrepancy between the different versions, the original French text will prevail.