Carbon credits How Swiss oil trader Mercuria is seeking to cash in on Brazilian forest

Adrià Budry Carbó, in collaboration with Manuel Abebe, November 12, 2025

It took just three days. On 20 September, the Brazilian press reported on a meeting between Public Eye and representatives of social movements in Tocantins (northern-central Brazil). The issue under discussion were carbon credits, generated in a jurisdictional programme for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (J-REDD+) launched by the Geneva-based trading giant Mercuria. Public Eye was said to have described this type of initiative as a “pseudo-solution” for combating the climate crisis, and to be preparing a “detailed” report. It remains to be written, but a number of parties in Brazil are demanding that we explain our interest in Tocantins and specify the “objective” of the report.

The “race” to Belém

This is a particularly sensitive topic because offsets of this kind are one of the main themes of the COP30 negotiations at Belém (10–21 November 2025), as part of efforts to achieve the Paris climate goals. The official programme allocates two days to the carbon market, showcasing jurisdictional J-REDD+ pilot schemes such as those in Tocantins and Pará, another Brazilian state where NGOs have condemned the pressures exerted on traditional peoples in connection with these programmes.

This market runs on carbon credits representing the equivalent of one tonne of CO₂ avoided or sequestered by an “offsetting” project which funds measures such as the protection or restoration of forests. J-REDD+ programmes use a historic baseline to evaluate how far the emissions attributable to deforestation and forest degradation have actually decreased across an entire jurisdiction, compared with the situation that would pertain if no measures had been implemented. Unlike the more local REDD+ projects, J-REDD+ programmes generate credits on much greater scale and are therefore potentially more lucrative. Any reduction in CO₂ emissions is recorded in the form of carbon credits, with part of the resulting revenue going to countries and communities that preserve their ecosystems.

The stakes are enormous, given that the state of Tocantins is experiencing very significant deforestation. Rapid agro-industrial expansion means that this state – which is nearly seven times the size of Switzerland – has a higher rate of forest loss than any other Amazonian state. The Cerrado biome, a tropical savannah characteristic of Latin America, covers nearly 91% of the state of Tocantins, which saw its rate of deforestation jump by 5% in a single year: according to data from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research, more than 223,000 hectares were destroyed in 2023. It remains to be seen how the local authorities and Mercuria intend to combat this trend in such a way as to be able to generate carbon credits.

Another key factor in the success of the whole business is that carbon offsetting schemes and projects cost less to implement in the places where they are administered than at the locations where the CO₂ is actually emitted. The difference in cost is precisely what makes them more attractive to commodity trading companies such as Mercuria, which has been active in this transnational market since 2008. Local politicians even take pride in the fact that “European countries have perhaps not implemented environmental protection policies in the same way we do,” as Wanderlei Barbosa, the governor of Tocantins, swaggered in a promotional video from June 2023 in which he appears alongside representatives of the Geneva trading house. A Brazilian columnist reports him as saying: “That's why multinationals the size of Mercuria involve themselves in environmental issues in other places, where they can make this kind of reparation.”

The trader is using its Singapore subsidiary Silvania, launched in 2023, to support the “Race to Belém” initiative, which aims to raise at least USD 1.5 billion for offsetting programmes in the Amazon and in regions close to the world’s largest rainforest. In addition to Tocantins, the trading house has also signed partnerships with the neighbouring state of Piauí, two of Peru’s Amazonian departments and an Argentinian province. The launch of a J-REDD+ project on Peruvian Indigenous lands was also announced in July 2025.

Silvania says that these programmes “prioritise Indigenous rights, cultural heritage, and sustainable development, empowering local communities as stewards of the forest”.

The promise of quick profits

The “stewards of the forest” do not necessarily agree. On 7 July 2025, an alliance of 11 communities from Tocantins – the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), communities of descendants of enslaved people (quilombos), family farmers and rural women’s groups – referred the matter to the Brazilian Federal Public Prosecutor's Office (MPF) and the Brazilian authority overseeing J-REDD+ projects, calling for the immediate suspension of the programme in their state. Why? Because the terms on which the Indigenous populations should be consulted – with a view to obtaining their free, prior and informed consent – have not been met, according to the complaint, which has been seen by Public Eye and is aimed squarely at the Tocantins Environmental Secretariat.

©

Ludimila Carvalho / VII Encontro Tocantinese de Agroecologia

©

Ludimila Carvalho / VII Encontro Tocantinese de Agroecologia

Under Article 6 of International Labour Organisation Convention 169, Indigenous and tribal peoples must be consulted prior to any legislative or administrative measure that directly affects them. Mining, oil or infrastructure projects undertaken by multinational companies frequently infringe on these granted rights. In countries which have ratified the convention, including Brazil, the absence of prior consultation (“consulta previa”) may lead to the operating permit being cancelled or suspended.

According to the signatories to the complaint, the workshops held by the Tocantins Environmental Secretariat “do not present any information enabling participants to understand what the Jurisdictional REDD+ programme actually is”; in fact, the discussions focus solely on how profits will be distributed.

The local authorities pulled out all the stops in their efforts to convince the population, dangling the prospect of an inflow of new money into the largely agrarian state of Tocantins. Paulo Rogério, coordinator of the Tocantins Network for Agroecology (ATA), a cosignatory of the complaint, was present at several such meetings in 2023. He recounts that the proceedings were attended not only by technical teams but also by “mandated community leaders, in order to bolster the programme’s acceptability”. “It was a complex conversation based on hypothetical data, such as ‘Do you want x million or not? Just take the money.’ It was a process of coercion, the communities were coerced,” he maintains.

50 million carbon credits

Between now and 2030, the state of Tocantins aims to generate 50 million carbon credits, including an initial tranche of 17 million for the 2020-24 “harvest”, as it is officially called. Each credit represents one metric tonne of carbon sequestered by its forests and native vegetation. According to the scarce information available, the revenues would be managed by a Climate Fund, whose organisational chart has not yet been made official, and would be shared out in the following ratio: 50% for the state, 25% for private farmers and 25% for Indigenous villages and quilombola communities.

The state is already forecasting revenues of BRL 2.5 billion (CHF 370 million). Calculating the financial benefits remains a speculative exercise, however, since the price of carbon credits fluctuates strongly. “We were told that the price of carbon credits was fixed by the market,” says Paulo Rogério, ATA coordinator, wryly.

This is where Mercuria enters the picture: according to the public documents we have consulted, the credits are to be sold to the market by Tocantins Carbono, a joint venture more than 95% owned by Mercuria (the rest being held by the state of Tocantins).

From black gold to “green carbon”

Mercuria, founded in Geneva in 2004, is mainly known as a trader in crude oil and refined products, natural gas and electricity. Having previously kept a low profile, the multinational found itself thrust into the spotlight in August 2025 when its co-founder Daniel Jäggi was a member of the informal “Team Switzerland”, which was tasked with defending Switzerland’s trading interests in talks with the Trump administration.

The Geneva-based commodity trader claims to trade more than six million barrels of crude oil per day but – on the grounds of its “distinct role [...] as an intermediary” – does not disclose any data regarding the indirect emissions generated by the use of the commodities it trades. Public Eye has estimated the latter at 496 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent in 2022 alone. Since then, the (in its own words) “most Swiss of the major commodity traders” has not published any further information about the commodities it trades.

To find out more, read our report 100 times more emissions than Switzerland: unadulterated truth about Swiss commodity traders' carbon footprint (2024)

Mercuria, besides marketing the carbon credits, is responsible for structuring the J-REDD+ programme in Tocantins. Furthermore, despite positioning itself as a simple “intermediary”, the company invested BRL 15 million in the foundation of Tocantins Carbono in 2022 (nearly CHF 3 million). “It’s a wager on the future,” says Brazilian scholar-activist Diana Aguiar, who has followed the programme’s public procurement process.

In return, the sale of every forest offset credit generated in the territory of Tocantins earns Tocantins Carbono a 3% commission. A further commission of 3.5% is received by Tocantins Parcerias, the entity that issued the programme’s call for tenders. Only after those payments can the rest of the bounty be shared among the various interest groups.

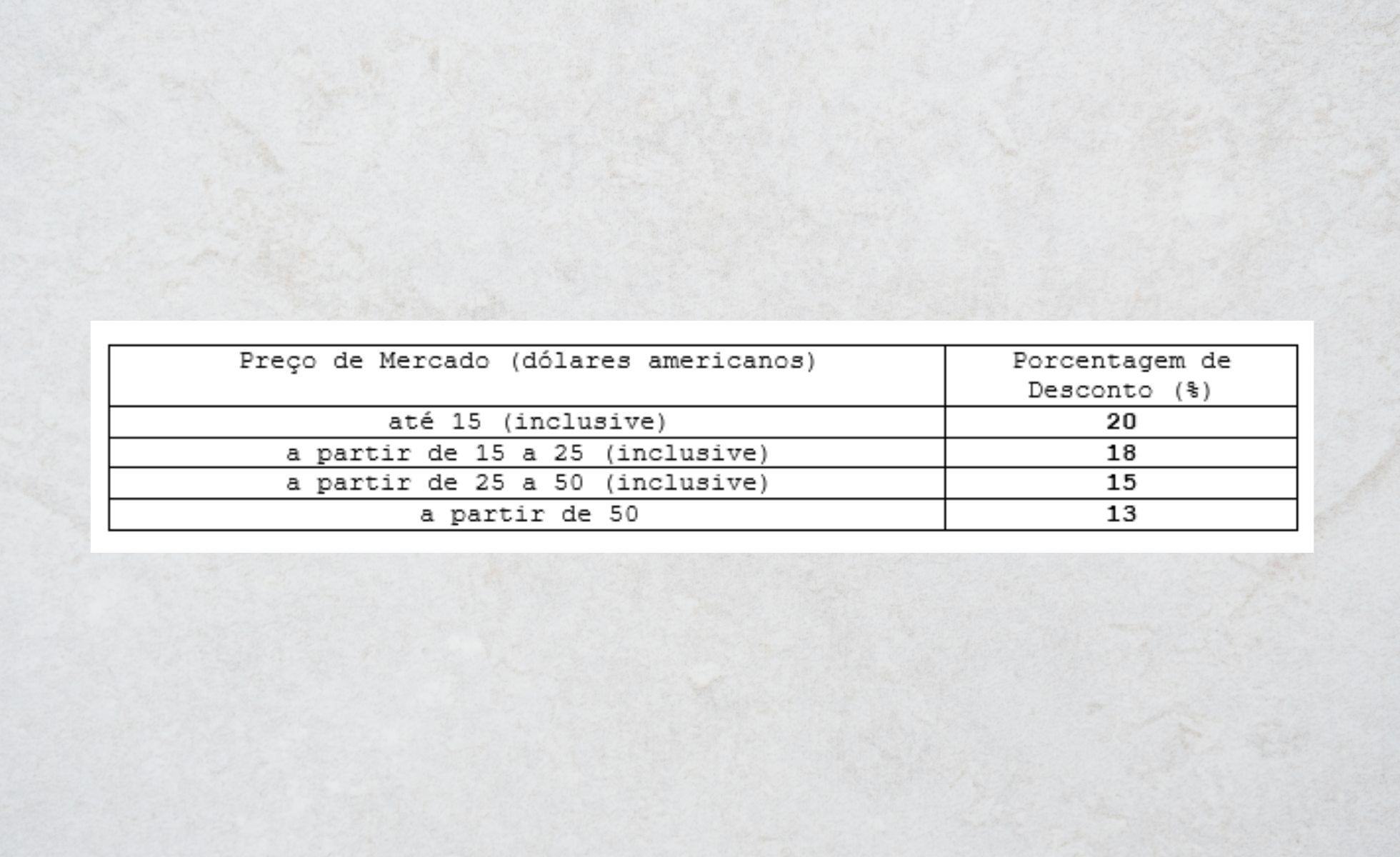

The contract contains another notable consideration for Mercuria. According to the confidential agreement between the commodity trader and the state of Tocantins, as seen by Public Eye, the trading house will benefit from sizeable discounts if it wishes to buy carbon credits: 20% when the market price is equal to or less than USD 15 per tonne and, on a sliding scale, a minimum of 13% if the price goes above USD 50. Elsewhere in the contract, the company clearly states its intention “of buying 100% (one hundred per cent) of the carbon credits generated” in Tocantins.

The commercial upside could be substantial. Based on the revenues of BRL 1.5 billion envisaged by the state of Tocantins for its 50 million carbon credits, one tonne of carbon would be worth USD 8.60. If Mercuria were to buy the 17 million carbon credits generated in 2020–2024 with its preferential discount of 20%, it looks to make a guaranteed profit of over USD 29 million. This kind of margin would appeal to any trading house – and that’s before mentioning the chance to speculate on a rising global carbon credit price. Meanwhile, using the same valuation, the traditional communities would receive – via as yet unspecified mechanisms – a sum of approximately USD 27 million.

Ultimately, the terms of the contract are so generous and so flexible that they could enable Mercuria to take most of the profits from the carbon credits for the entire duration of a contract that runs to the end of 2032.

Public Eye put all these points to Mercuria and twice repeated its request for comment, without receiving a response to its questions.

Amazonia, the new Eldorado for traders

Trading companies are interested in the “green lungs of the planet” because carbon credits are a product that can be exchanged on a global scale, just like a barrel of oil, a tonne of coal or an ounce of gold. According to their inventor, carbon credits are “a commodity that you can’t see, smell or feel”. They have the advantage of being a paper-based commodity, which does not have to be stored or transported and bestows a façade of virtue. Above all, they promise increasing returns as the 2050 deadline approaches – the target date set by the Paris Agreement for achieving carbon neutrality and keeping global warming below 1.5 °C.

©

© Website Silvania © Victor Moriyama / Greenpeace

©

© Website Silvania © Victor Moriyama / Greenpeace

A study by consultancy firm McKinsey in 2021 says that the voluntary carbon market could exceed USD 50 billion in 2030. As far as Mercuria is concerned, the economic logic is irrefutable: J-REDD+ credits could become the most sought-after climate commodity of the decade. The more that countries fail to reduce their domestic emissions, the more the value of the credits will rise, in a mechanism familiar to any trader.

Numerous offsetting initiatives are based on largely exaggerated assumptions of deforestation, allowing programme developers to generate and sell more credits than appropriate. In July 2025, ratings agency BeZero Carbon graded its first J-REDD+ programme, concluding that the likelihood of a carbon credit corresponding to a real tonne of carbon emissions was “moderately low”. The result underlines the major integrity risks that continue to persist in forest carbon projects.

A procedure fraught with potential conflicts of interest

In Tocantins, representatives of the powerful agricultural trade sector are no more convinced by the programme than the traditional communities.

“Imagine deciding not to cut down a tree in your garden so you could sell someone else the right to cause the equivalent amount of damage. It's ridiculous. Nature doesn’t gain anything from it,” declares Paulo Corazzi.

He is a representative of Aproest, an association of agricutural producers, and regularly criticises the carbon credits “scam” on his Instagram page.

A legal analysis seen by Public Eye condemns the violation of farmers’ land rights and the opacity of the entire process – particularly through the establishment of private entities in order to circumvent public transparency standards in Brazil. It also regards the profit distribution system as compromising national sovereignty.

In addition to giving Mercuria the opportunity to purchase all the credits it trades, the programme presents other risks of conflicts of interest. According to official documents consulted by Public Eye, Geonoma, a company in which Mercuria now has a 50% stake, is responsible for the technical aspects of the project with regard to the volume of carbon credits generated. One of its directors is also a director of Tocantins Carbono and Mercuria Brasil.

For Winnie Overbeek, a researcher with the World Rainforest Movement,

“the architecture of this kind of programme is a standing invitation to manipulation and fraud. Everyone has an interest in generating more credits because all the stakeholders receive commission on their sale. They have no plan for reducing emissions but merely promise greater control.”

The schedule for the public tender for the Tocantins J-REDD+ programme also raises questions. Public Eye has examined the documents relating to the procedure, which show that Tocantins Parcerias, the entity created by the state, allowed the candidate companies only two weeks in which to present their projects. According to the special selection committee, the bids by the other two candidates, both of which are consultancy firms, were rejected for failing to meet “the minimum selection criteria for partnership”, such as lacking financial capacity, or because they submitted documents in a foreign language.

Meanwhile, the authorities are vigorously pursuing J-REDD+ policies, to the point where the law governing the state of Tocantins’ carbon credit policy came into force at the start of 2023 – that is, after the entire tendering process had ended.

Corruption and “green” land-grabbing

The state of Tocantins, which was founded in 1998, has undergone numerous corruption scandals. Three governors have been dismissed for irregularities during their terms of office. The latest, Wanderlei Barbosa (the person who appeared alongside Mercuria), was suspended for six months on 3 September this year, as was his wife, who also held public office. They, together with members of the previous government, were said to be involved in a corruption scheme related to the misappropriation of food parcels during the Covid pandemic.

Environmental Secretary Marcello Lelis, who oversaw the J-REDD+ scheme and is a favoured contact of Mercuria, was also dismissed shortly after Wanderlei Barbosa. Previously, he had been handed an eight-year disqualification from office for “abuse of economic power, excessive acquisition of fuel and hiring excessive numbers of electoral campaigners” when standing for election in 2012. Ironically, the corruption scandals hitting the region could adversely affect the J-REDD+ project supported by the authorities. “The value of the carbon credits to be traded on the markets largely depends on Tocantins’ reputation as a state,” says researcher Diana Aguiar.

Meanwhile, the traditional communities fear that J-REDD+ schemes will exacerbate something they are already enduring: land grabbing under the guise of ecological preservation, or “grilagem verde” as it is called locally. In Brazil, the environmental land registry, which operates on the basis of self-declaration, is often used by landowners as a means to seize preserved land by registering it as their own for the purpose of Legal Reserve compensation.

However, “nearly all the fifty or so quilombos in the region have no title to their land. The same applies to some Indigenous villages,” says Paulo Rogério, emphasising how historically charged the issue of land is. The ATA representative believes it is imperative to regulate land ownership before establishing a J-REDD+ programme: “These programmes constitute a new attempt to appropriate land that has so far been preserved, and to transfer it to companies. Everyone will be affected by this enclosure process.”

Having received no response from the authorities, in early September the coalition formed around ATA and Paulo Rogério filed a new complaint with the 6th Chamber of the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office, which defends the rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities; the complaint calls for the suspension of the J-REDD+ programme. In mid-October, the 6th Chamber referred the case to the Federal Prosecutor in Tocantins.

Inside the carbon credit jungle

As COP30 approaches, the legal framework of the J-REDD+ programmes remains unclear, to say the least. The Brazilian Federal Public Prosecutor's Office has requested that the programme in Pará, the neighbouring state, which is hosting COP30, be suspended immediately. The prosecutors allege that the local government has participated in a pre-sale of carbon credits, which would be in breach of national legislation. “These credits don't even exist yet,” declared Felipe de Moura Palha e Silva, Chief Prosecutor, in an interview with the environmental media organisation Mongabay.

In Peru, the authorities in the Amazonian region of Ucayali also signed an agreement with Mercuria in December 2021 with a view to developing a J-REDD+ programme. This is currently being challenged by the central government, which argues that regional governments cannot trade carbon credits until a national accounting system is in place.

In Tocantins, Mercuria has tried to head off any unforeseen problems. The contract signed with the regional state stipulates that the latter must “take all necessary judicial and administrative measures” against any law or regulation that could hamper the J-REDD+ programme.