Switzerland – hub for offshore companies

©

Keystone / Urs Flüeler

©

Keystone / Urs Flüeler

The reports issued to MROS clearly show how often legal persons (e.g. shell companies, trusts, foundations) are involved in corruption cases. The data collected show that significantly more companies (nearly 60%) than natural persons are reported in connection with suspicions of corruption.

The dirty money from large international corruption cases is often placed in shell companies abroad. However, Switzerland plays a key role, for these structures are often managed by fiduciary companies or law firms in this country. In nine out of ten cases reported to MROS, companies which are suspected to be laundering the proceeds of corruption are headquartered abroad; the majority are based in Central America and the Caribbean.

A shell company is a company that is set up in a foreign jurisdiction, mostly with a privileged tax system and a regulatory framework that guarantees confidentiality. In April 2016, the Panama Papers revealed the extensive business of companies headquartered in offshore jurisdictions (e.g. Panama, British Virgin Islands) and their huge involvement in illegal activities. A spotlight was shone on the intermediaries who set up such companies. The law firm Mossack Fonseca had even set up companies without even knowing the beneficial owners.

The scandal also covered the dubious role played by Switzerland. Over 38,000 of the offshore companies identified by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) had been set up by Swiss intermediaries.

A researcher at the University of Sussex created a clear graphic depiction of the connections between shell companies cited in the Panama and Paradise Papers (2017) and Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs). His study shows the role of Switzerland “serving as relations and administration centers for companies incorporated elsewhere on behalf of clients from most regions of the world”.

Alongside the companies set up from Switzerland, many other offshore companies have been linked to Switzerland through bank accounts that were set up in the country under their names.

In 2017, the federal government stated that such companies presented a “high risk” for Zurich, Geneva and Lugano as financial centres.

©

GettyImages / fanjianhua

©

GettyImages / fanjianhua

Complex structures and constructs

In Switzerland as well as internationally, there are different types of business structures, which have become an integral part of the global financial landscape. However, they can be used to serve illegal purposes such as money laundering or corruption. Opaque company structures make it possible to conceal illegal activities while at the same time protecting the anonymity of beneficial owners.

More infos

-

The role of domiciliary companies in corruption scandals

Domiciliary companies carry out no operational activities, i.e. they neither produce nor trade goods. They are categorised as ‘shell companies’, because in most cases their primary function is to provide a company that does not undertake any normal operational activities with a postal address.

Domiciliary companies headquartered in Switzerland or abroad are involved in 38% of proven corruption cases in Switzerland. According to the Swiss authorities, they pose a significant risk in the fight against money laundering. Their involvement or their use is illustrated, among other scandals, by the Odebrecht affair. In relation to this case, the Office of the Attorney General described “a sophisticated system of companies for the payment of bribes” and highlighted the role of intermediaries.

-

Trusts frequently connected to money laundering

(Click to enlarge the graphic)

Trusts are generally not legal persons. Their legal status lies between a fiduciary company and a foundation. Certain assets can be entrusted to one or several persons (trustees), who manage the assets and use them for a predetermined purpose by the settlor (person who set up the trust). Trusts can have one or several beneficiaries. Their structure is very opaque.

This legal structure is not identified in Swiss law. Trusts were only given a legal definition when the Hague Trust Convention was ratified. It came into force in Switzerland in 2007.

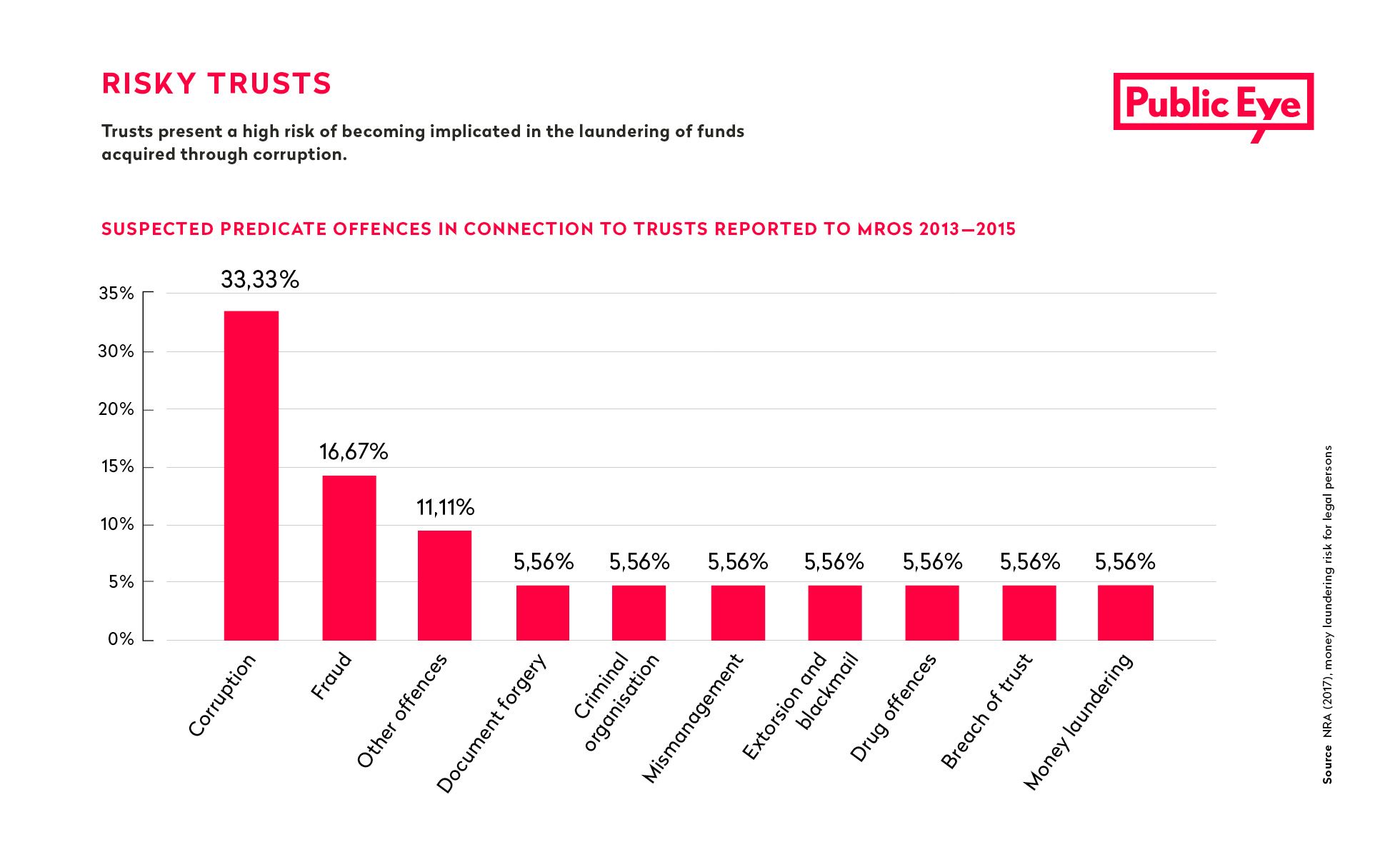

Trusts are at high risk of becoming connected to the laundering of corrupt assets. Corruption comprises a third of the suspected predicate offences involving trusts that were reported to MROS from 2013 to 2015.

The role of Swiss companies in corruption and money laundering systems

Swiss companies are used as vehicles for corruption and money laundering, whether as a so-called operational company or a domiciliary company. The latter can still conceal the identity of the beneficial owner in Switzerland.

More infos

-

Operational companies

A company counts as operational if it was set up to undertake an industrial or commercial activity. Cases of suspected money laundering connected to corruption abroad mostly involve legal persons from Switzerland that are operationally active companies, often from the fields of financial advisory or asset management firms. A perfect example is the Odebrecht case. Assets originating from the bribery of foreign officials went straight to Swiss bank accounts. Mostly they were first introduced into the legal financial system via other jurisdictions before they end up in Swiss bank accounts.

-

Domiciliary companies

Companies with no operational activities do not necessarily serve dubious purposes, but this form of company is most frequently used when the aim is to conceal the identity of beneficial owners in Switzerland. Until recently, Swiss corporations, cooperatives and foundations enjoyed the privileged cantonal tax status reserved for domiciliary companies. Trusts, fiduciary companies and foundations were able to benefit from this status too. Since the 2019 corporate tax reform, the tax privilege for domiciliary companies no longer exists. Due to the lack of a public register on the beneficial owners however domiciliary companies remain vulnerable to abuse.

A dubious Belarussian bank in the hands of a Freiburg-based shell company

In 2012, the US Department of the Treasury decided to place the Belarussian bank Credex on a black list under the 2001 Patriot Act. The US authorities suspected the bank – which in terms of its capital is ranked 22 in its country – of money laundering. From January to March 2010, it is alleged to have transferred approximately USD 1 billion to offshore companies headquartered in the British Virgin Islands and other jurisdictions. At the time period in question, the bank was 96.82% owned by the shell company Vicpart Holding, which was headquartered in Freiburg and had neither an office nor employees. Its address was at a Freiburg building at which over 200 companies are registered. It was managed by a CEO from Geneva – whose job role was limited to owning Credex shares. The US authorities have taken similar measures against nine further financial institutions. It has never been possible to identify the real owners of Vicpart. The Freiburg-based company was closed down in January 2013.