Patent "evergreening" Abusive pharma patents: Roche’s “mAb” empire

Patrick Durisch, November 6, 2025

Herceptin has been one of Roche’s biggest commercial successes since it was introduced in the late 1990s in the United States, Switzerland and the European Union (EU). It is used to treat HER2+ breast cancer, a particularly aggressive form of the disease which affects worldwide more than 400,000 new people every year. So far, Herceptin and its three follow-on products – Perjeta, Kadcyla and Phesgo – have enabled Roche to achieve a cumulative revenue in excess of CHF 156 billion – making it a real gold-mine.

How can such a long-term, profitable bonanza be explained in a pharmaceuticals market that is supposed to be highly competitive? No-one would argue that Herceptin marked an important advance in the therapeutic arsenal available for treating this cancer. But this isn’t the only reason behind its success. What Roche has actually done is to use and abuse various tactics to extend its monopoly and keep rival products off the market for as long as possible, as revealed by our investigation.

In this second episode of our series on abusive monopolies dominating the pharma industry, we have closely scrutinized the patents protecting these four treatments. Consisting of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), trastuzumab and pertuzumab belong to the family of “biological” drugs, protected by a host of patents.

A drug is said to be “biological” when it is made from living cells or organisms. These “biologics” are more complex to produce than chemical, small-molecule drugs made from inert substances, which means that a greater number of patents are involved, particularly in relation to manufacturing processes. It is these patents that hinder the development and marketing of generic drugs named “biosimilars”.

More infos

-

Public Eye series on abusive patenting in the pharmaceuticals industry

Public Eye has been documenting and exposing facts of public interest for many years. In September 2024, we launched a series to highlight the abusive use of patents filed for best-selling medicines, a practice that has an impact on healthcare costs in Switzerland and elsewhere. This article is the second case study in this series. The first on Novartis’ Entresto is available online and in the September 2024 issue of Public Eye’s magazine (in French and German).

A barricade of patents

We have identified a total of 183 patents granted to Roche linked to these two molecules in the United States and 95 in Europe, also valid in Switzerland. By the end of September 2025, 100 and 64 respectively were still in force in the United States and Europe. About twenty additional patent applications were still being examined on both sides of the Atlantic (see diagram below).

In the absence of any existing inventory, we identified the patents using official sources. To compile this exclusive list of patents linked to trastuzumab and pertuzumab, we relied on court documents, regulatory authorities register, national patent offices and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) databases, as well as scientific articles and other publications on the subject. Given how difficult it is to reconstruct such a landscape, the actual list of Roche’s patents for these treatments may be even longer.

More infos

-

Roche’s drugs for treating HER2+ breast cancer

Our investigation focuses on the four drugs marketed by Roche for treating HER2+ breast cancer.

Herceptin: The first drug developed by Roche/Genentech against this disease contains the molecule trastuzumab. This is one of the company’s biggest commercial successes, generating more than CHF 100 billion in sales to date. In 2024, despite the arrival of biosimilar competitors on the market, Herceptin still ranked 12th in Roche’s overall sales, with nearly CHF 1.4 billion.

Perjeta: Available on the market since 2012, it has been among Roche’s top five sellers for the last 10 years, generating over CHF 34 billion in revenue since its launch. It contains the pertuzumab molecule and is usually taken in combination with Herceptin and chemotherapy. This combination treatment cost more than CHF 100,000 per year until 2022 in Switzerland, before the price of Herceptin dropped due to biosimilars arriving on the market. Public Eye has extensively documented and exposed the excessive price of this treatment.

Kadcyla and Phesgo: Available on the market since 2013 and 2020 respectively, these two drugs are also based on the molecules trastuzumab and pertuzumab. Phesgo is a fixed-dose combination of Perjeta and Herceptin in a single vial. Their marketing has enabled Roche to tighten its monopoly on all these treatments.

Thicket of secondary patents

Only 5 percent of these titles are primary patents, which protect the active substance. The remaining 95 percent are secondary patents claiming a manufacturing process (40 percent), formulations, dosages or modes of administration (30 percent), methods of use (13 percent) or combinations with other active substances (12 percent).

These secondary patents do not cover the active substance, which remains identical. However, patent offices are flooded with them, requiring multiple examinations – at the risk of granting them too easily due to excessive workload – while they extend the duration of the monopoly without offering any real therapeutic benefit.

Known as “evergreening”, this abusive accumulation of secondary patents for therapeutic products is a common practice in the industry, allowing the holder to delay the marketing of rival products and extend its monopoly of a given treatment.

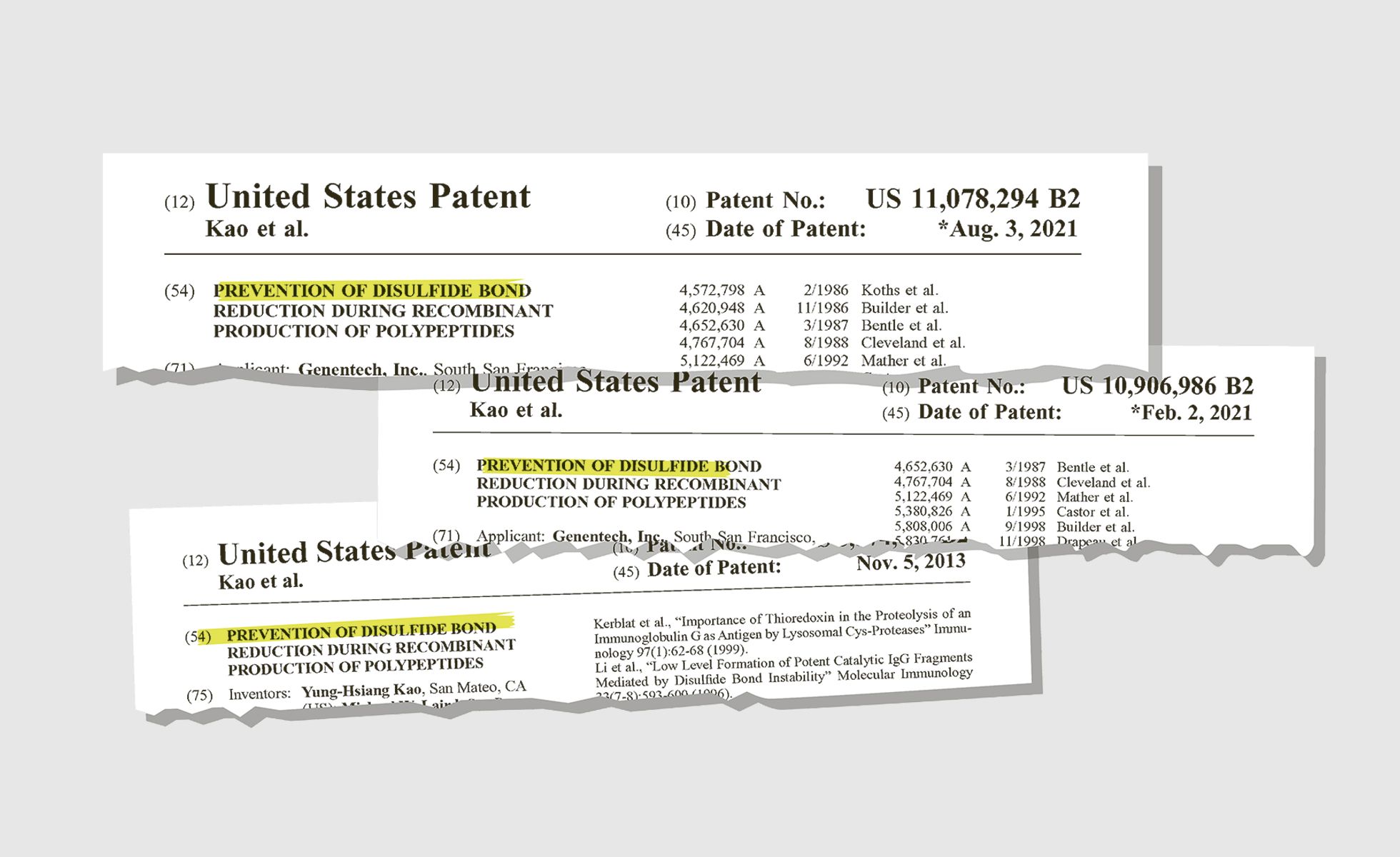

In the case of trastuzumab and pertuzumab, for example, we identified 16 secondary patents filed by Roche in the United States, with perfectly identical titles, 13 of which have been granted.

Another strategy called “product hopping” involves launching a new version of a product whose primary patent is about to expire. Shortly before its primary patents protecting Herceptin elapsed, Roche changed its mode of administration from intravenous to subcutaneous injection and protected it by filing several secondary patents, effectively extending its monopoly. This new mode of administration for an existing product is indeed more convenient for medical staff and patients. However, does it justify allowing a monopoly at a very high price for 20 more years?

The launch of Perjeta and Phesgo on the market, 14 years and 22 years respectively after Herceptin, also extended the Swiss company’s monopoly. The patents covering them have tightened Roche's stranglehold further on this market until 2042 in the United States and 2039 in Europe and Switzerland.

Overall, since filing its first patent in 1992, Roche has secured a monopoly of nearly 50 years in the United States and 47 years in Europe for its product Herceptin. This is more than double the 20 years provided for by the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement on intellectual property (TRIPS).

Patent litigations to hold back competitors

The primary patent for Herceptin expired in 2014 in Europe and 2019 in the United States. So far, seven biosimilars (biologic generics) have entered the market. They are not available everywhere, and only for intravenous use, as the subcutaneous version of Roche’s products is still protected by secondary patents until 2038.

Since 2017, Roche has filed several lawsuits against biosimilar manufacturers in the United States as soon as they had applied for market approval with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). We have counted eight complaints, covering a large number of patents: seven between 2017 and 2023 against manufacturers of Herceptin biosimilars for alleged infringement of up to 40 patents, and one last August 2025 against a manufacturer of a Perjeta biosimilar relating to 24 of its patents (see table below). One striking detail stands out: 88 percent and 80 percent respectively of the patents cited in Roche’s complaints were filed after the original product was placed on the market. In other words, the disputes raised are defending processes that were not used by the Swiss pharma giant to manufacture and launch its own products.

Consequently, biosimilars typically reach the markets in Switzerland, Europe and the USA only long after the primary patent of the originator’s drug has expired. This leads to unnecessarily lengthy high monopoly prices paid by patients and health systems.

Court battles in India and South Africa

Roche is also pursuing legal battles in other countries. In India, under the threat of a compulsory licence, the Swiss firm relinquished its only patent for Herceptin in 2013, an extremely rare move in this sector. However, a few months later, it filed a complaint against a manufacturer of biosimilars. Although the outcome did not go in its favour, Roche was able to delay the marketing of a rival product by three years.

In 2024, Roche sued another Indian manufacturer of a biosimilar of Perjeta for alleged infringement of its two patents – first successfully, before the Delhi High Court had a drastic change of mind. The proceedings are still underway.

In South Africa, competition authorities filed a complaint against Roche in 2022 for alleged excessive pricing of its Herceptin. Deliberations are ongoing. The arrival on the market of a Herceptin biosimilar in 2019 has helped reduce the price of intravenous treatment. However, nearly 25 years after the product was launched in the country, its subcutaneous form, still patented, remains unaffordable for the majority of patients in South Africa.

The price of monopoly

In South Africa and other countries, secondary patents and the resulting monopoly provide Roche with powerful leverage, allowing it to impose its excessive prices for HER2+ breast-cancer treatments, as we have already documented as far back as 2018. In Switzerland, Roche has no qualms about exerting pressure on the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) to impose its prices. In 2014, the Basel-based company was unhappy with the price set by the federal government and removed Perjeta from the list of medicines reimbursed by the compulsory health insurance scheme. This blackmail paid off for the company, as Perjeta was reintroduced a year later with a higher real (net) price.

This summer, Roche followed the same playbook for another of its cancer drugs, Lunsumio. As of early November, it still has not appeared back on the list of medicines reimbursed by the basic insurance scheme.

The “mAb” empire

Thanks to the barricade of patents it has erected over more than 30 years, Roche has secured a very dominant position in the field of HER2+ breast-cancer treatments, and more generally in treatments involving monoclonal antibodies (“mAbs”).

These therapies are based on decades of academic research and have been backed by hundreds of millions in public funds. They are vital for many people and could have been supplemented by more affordable biosimilars following the expiry of the primary patents. However, they are often still inaccessible and incur significant additional costs in the healthcare sector. In Switzerland, this practice has a direct impact on the level of insurance premiums. In its latest report on medicines, the health insurer Helsana estimates the potential savings from using already approved biosimilars more frequently at CHF 1.2 billion between 2020 and 2023 alone.

If Switzerland were to actively intervene against monopoly abuses that delay the introduction of new biosimilars, this potential for savings would increase drastically. The authorities in countries hosting large pharmaceutical companies, such as Switzerland, must, as a matter of urgency, speak out against the abusive proliferation of secondary patents on medicines. As a member of the European Patent Convention, Switzerland could request a more meticulous examination of patent applications to limit the numbers of unmerited patents.

The U.S. government's current efforts to lower the price of patented drugs may well produce only limited results, as negotiations with pharma corporations focus on the official list price – a fictitious reference pricing used for international comparisons – rather than the actual real prices paid by health systems and patients. Worse still, the price of medicines in Europe and in Switzerland may increase in return if pharma companies follow through on their threats. Meanwhile, abuses of the patent system and the grip of pharma giants on entire segments of the sector will just carry on if nothing is done.

More infos

-

Part 1: Entresto, one year on

In the first episode of this series, published in September 2024, we revealed the tactics used by Novartis to delay the arrival of generic versions of its heart-failure drug, Entresto. Protracted litigations have allowed Novartis to gain additional monopoly time before the arrival of generics on the U.S. market mid-2025, which translates into four billion dollars sales revenue. More than two years after the expiry of the primary patent (2023), no generic version of Entresto has yet entered the market in Europe.

By contrast, Indian courts decided to revoke Novartis’ final secondary patent for Entresto last September, citing a lack of novelty and inventive step – a textbook case of “evergreening”. This was the last patent threatening the marketing of generic alternatives. Novartis can still appeal against the decision.

What is a patent?

A patent is an exclusive right that allows the holder of an invention to prohibit third parties from manufacturing and marketing it in the countries where such protection has been granted. This invention must meet three requirements to be patented: be novel, involve an inventive step, and be capable of industrial application. Therefore, a minor modification of a medicinal product with no therapeutic added value can be patented.

There are two main categories of patents in the pharmaceutical sector: primary patents relate to the drug’s active substance(s), while secondary patents are intended to protect modifications of already patented drugs. In practice, the latter artificially extend the duration of commercial exclusivity.

The term “patent thicket” is used when a drug is protected by numerous patents. When they are filed over time, the duration of the product’s monopoly can well exceed the 20 years provided for by international law.