Commerce in Context: Foreign Economic Policy

Commercial policy, and in particular bilateral free trade agreements, are a central pillar of foreign economic policy. How should Swiss foreign economic policy be structured to ensure a sustainable and human rights-compliant commercial policy – and forward-looking foreign economic relations in general?

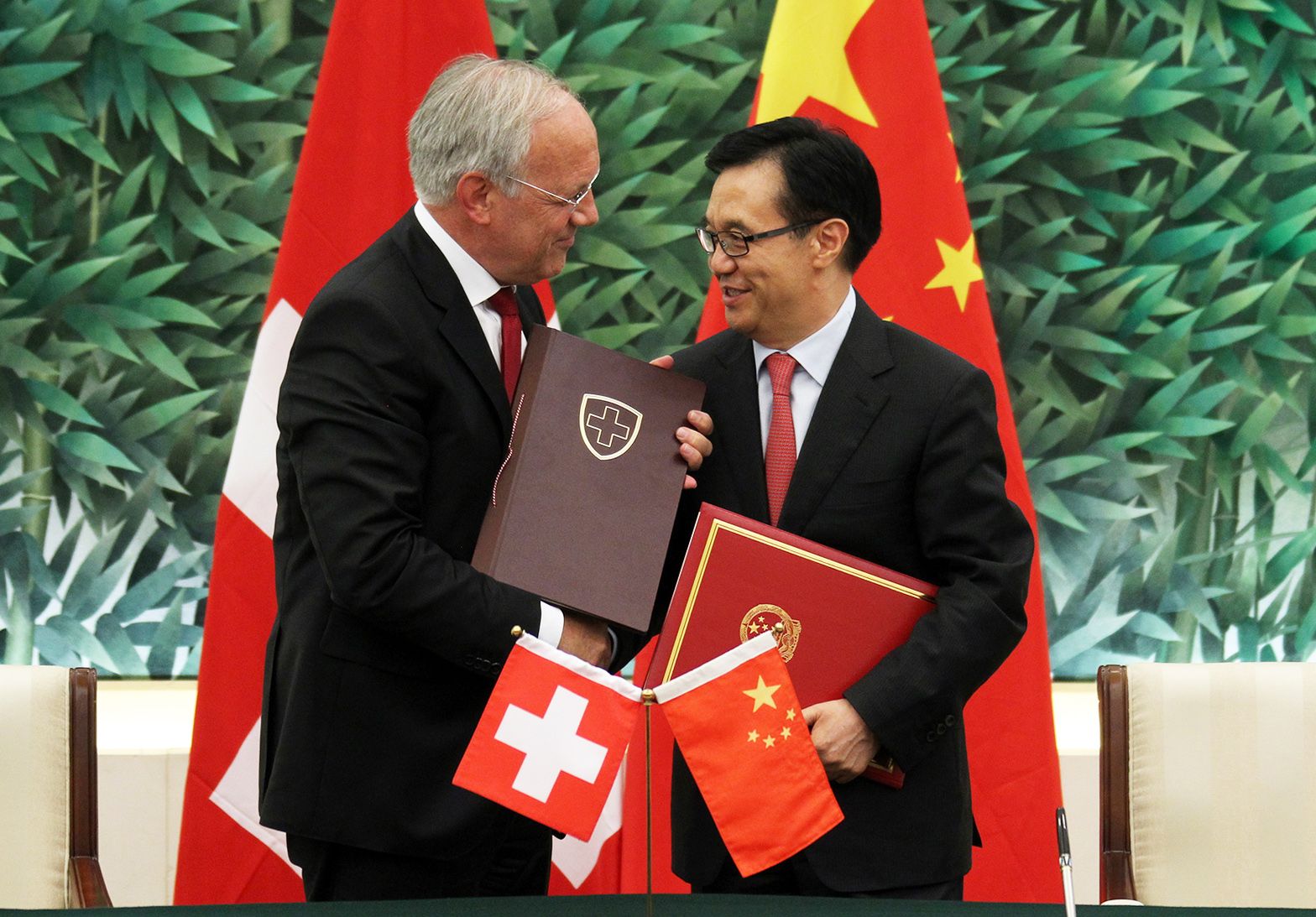

For example, there is the question of how to deal with products produced through the use of forced labour in terms of trade policy, as the Federal Council seems to be moving away from the long-held paradigm of “Wandel durch Handel”, or “change through trade”, as a result of its experiences with China; and this goes beyond the specific case of Chinese imports from the Xinjiang region. Under what conditions should trade restrictions (trade sanctions and embargo measures) be imposed in the event of serious human rights violations, and according to what regulations?

In the case of totalitarian regimes, the tension between economic interests and the protection of human rights and other sustainability concerns poses a particular challenge.

With the number of autocratic governments around the world on the rise, finding satisfying answers to these issues is all the more urgent. This does not just concern the conclusion of further free trade agreements, but Swiss economic relations in general, e.g. with Belarus, Turkey or, currently, with Burma.

©

Keystone / Xinhua / Xing Guangli

©

Keystone / Xinhua / Xing Guangli

In view of the deteriorating human rights situation in many countries, which in the case of the Uighur population in China is classified as a crime against humanity (and thus as a violation of the peremptory norms of international law), Switzerland must define clear red lines in its external economic relations in order to prevent it from being exposed to accusations of complicity. The same applies in relation to the environment – the urgency with which the climate crisis, biodiversity loss and the depletion of natural resources must be tackled requires swift and consistent action in all policy areas, including trade policy, as well as a broad-ranging discussion on red lines that must not be crossed in order to prevent further environmental destruction.

Strategy without a legislative basis

At the end of 2021, the Federal Council adopted a new strategy regarding foreign economic policy. However, this strategy is unilaterally aimed at promoting the prosperity of the Swiss population and thus at the country’s own economic interests. In the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, Article 54(2) defines not only the safeguarding of Swiss welfare, but also respect for human rights and the preservation of natural resources as foreign policy objectives – this is what the country’s international trade policy must be oriented towards.

However, these constitutional provisions are considered to be normatively weak; they need to be put into concrete terms. Indeed, there is a federal law on international trade measures that dates back to 1982. However, it mainly comprises technical procedural provisions, is limited to the protection of the Swiss economy, and does not provide any guidance in relation to contemporary international policy development.

Switzerland needs a foreign economic law

An important concern of a foreign economic law (FEL) is the promotion of Swiss economic interests abroad in a way that is in line with foreign policy objectives and international obligations. Fundamental questions about our trade relationships should no longer be decided on a point-by-point basis and within the framework of negotiations on free trade agreements, but should instead follow transparent, legally defined principles, goals and priorities.

As such, the FEL should, for example, clarify the prerequisites for preferential trade relations and how the corresponding agreements should be structured in order to guarantee Switzerland the necessary freedom to act with regard to the safeguarding of human rights. Linked to this is the question of what economic policy measures are appropriate against totalitarian regimes and what regulations should apply to trade sanctions and embargo measures.

©

Franziska Rothenbühler / GfbV

©

Franziska Rothenbühler / GfbV

Enhanced transparency and democratic legitimacy

Federal Council regulations in the area of foreign economy, as well as their implementation by the federal administration, are not very transparent, especially when it comes to external trade relations, and therefore avoid public scrutiny. In contrast to the EU, the negotiating mandates for free trade agreements that are issued by the Federal Council are not public, thus hindering debate on targets, priorities and red lines. This lack of transparency has also been criticized by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) newspaper: “The time of secret diplomacy – of authorities thrashing things out behind closed doors and then presenting their wide-eyed subjects with the result of their negotiations – is over.”

In addition to substantive provisions, a foreign economic law should also define participatory procedures.

The Federal Council’s strategy promises a “participatory foreign economic policy” – this must now be given a solid legal basis. Parliament and civil society must be able to influence the shaping of foreign economic policy from an early stage. Improved participation, transparent processes concerning the implementation of targets, and comprehensible decision-making procedures for dealing with conflicts of interest all serve to strengthen the democratic legitimacy of foreign economic policy.