Research Banned pesticides on our dinner plates

Laurent Gaberell & Géraldine Viret, June 1, 2020

Carbofuran, permethrin, profenofos, triadimefon, diazinon, carbosulfan: these are the cryptic names of ingredients hidden in a sweet pepper produced in Vietnam and sold in Switzerland. If the presence of these banned pesticides was indicated on the pepper’s label, it is safe to say most people wouldn’t touch it.

This example is only a foretaste of a reality that, while disturbing for consumers, is especially dramatic for the farmers who, thousands of kilometers away, grow fruits and vegetables using pesticides too dangerous to be approved in our own country.

-

©

Rojo Mabilin

©

Rojo Mabilin

-

©

Atul Loke / Panos Pictures

©

Atul Loke / Panos Pictures

-

©

Atul Loke/Panos

©

Atul Loke/Panos

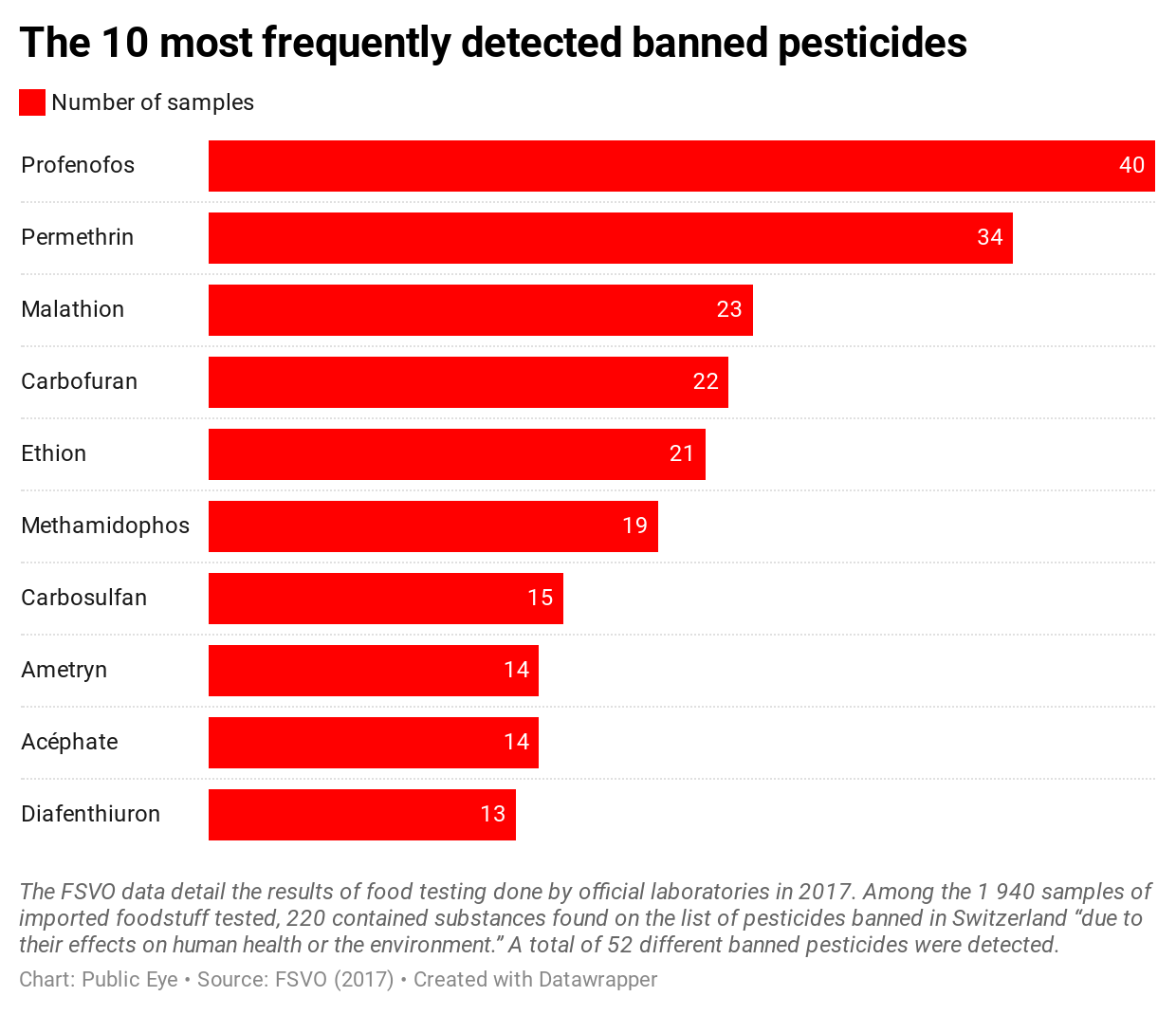

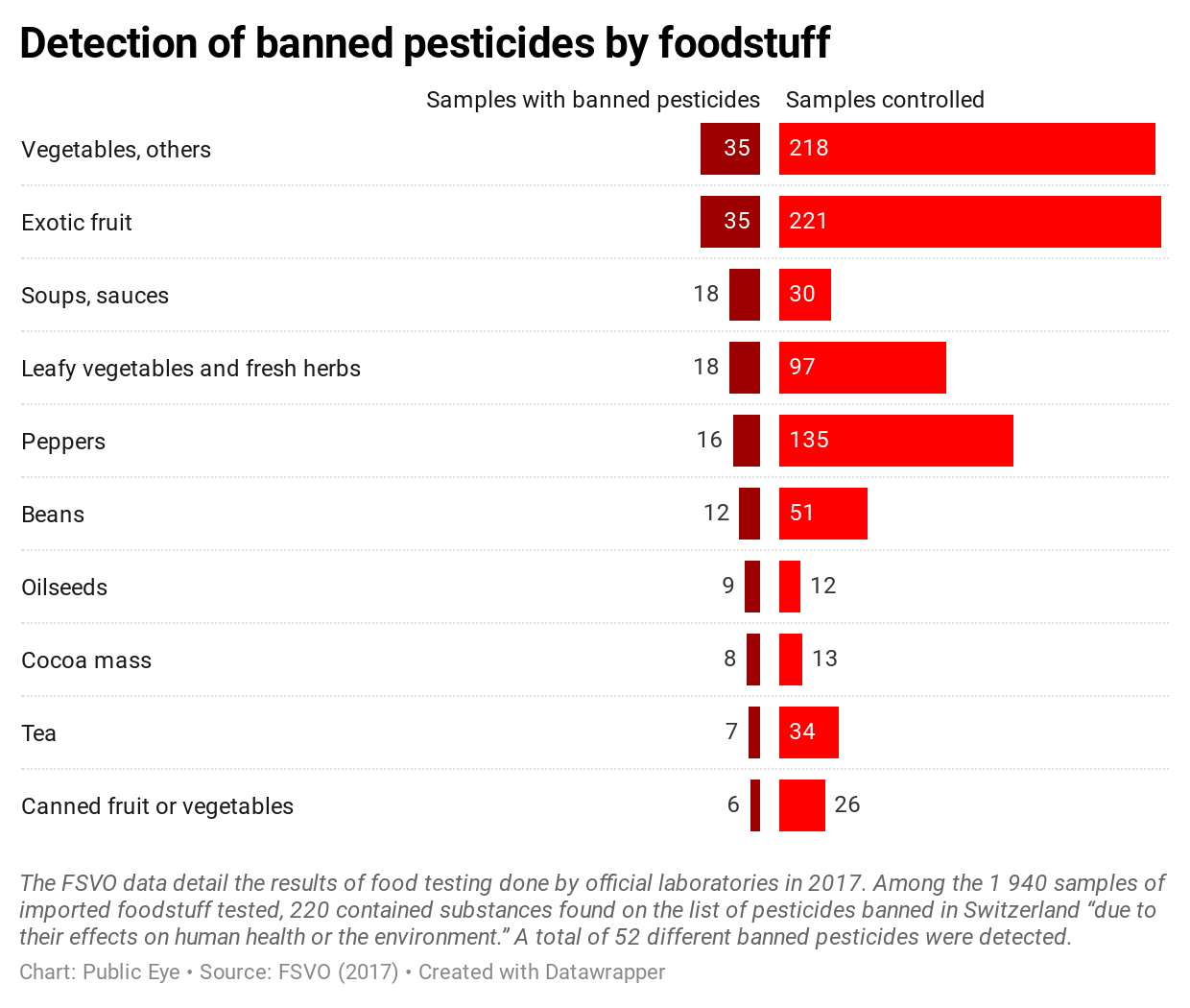

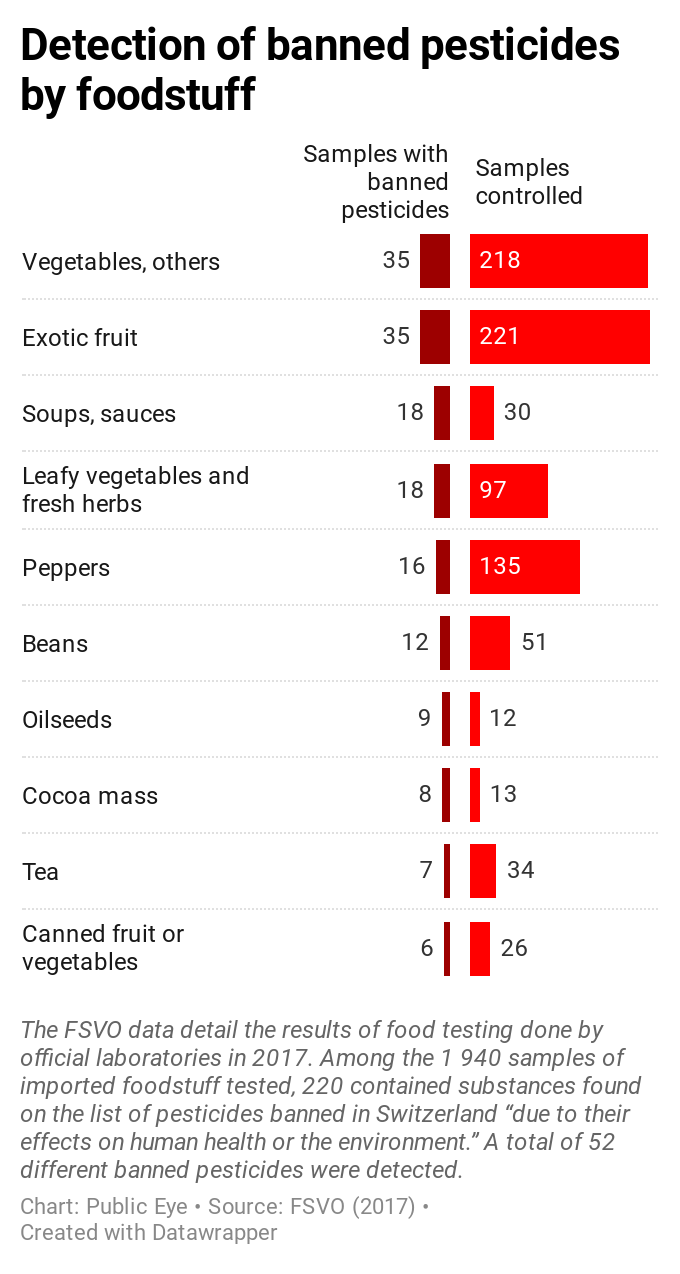

According to our investigation, which draws on data from the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (OSAV), more than 10 % of imported foods tested by the authorities in 2017 contained residues of pesticides banned in Switzerland because of their harmful effects on health or the environment.

No less than 52 banned pesticides were found in that year’s testing. At the top of the list were substances that even at low doses can have devastating effects on health in case of repeated long-term exposure, even at low doses, or that present a high risk of acute poisoning of farmers. The foods containing the pesticides were legally imported from countries where their use is still authorized.

Ironically, among the banned pesticides most frequently detected are substances marketed by the Swiss giant Syngenta, or even exported from Switzerland in recent years. Through food imports, these pesticides find their way back to our dinner plates.

“This is an unacceptable double standard,” reacted Michael Fakhri, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to food.

“If a country bans the use of pesticides because they are deemed to be too dangerous, it should not allow its companies to export them, nor should it accept the import of food produced with these substances.”

The OSAV data detail the results of food testing done by official laboratories in 2017. These are the most recent data available at the national level. Each food sample is tested for more than 450 different pesticides. The foods – fruits, vegetables, spices, canned foods, tea – are selected on the basis of suspicion or according to the risks, i.e. focusing on pesticides or products originating from countries where a number of exceedances of maximum residue levels have been observed in the past, according to OSAV.

Among the 1 940 samples of imported foodstuff tested, 220 contained substances found on the list of pesticides banned in Switzerland “due to their effects on human health or the environment.” For foods originating from third countries (outside the European Union), where pesticide regulation is generally weaker and less strictly applied, the proportion reached nearly one out of five samples.

Pesticides with devastating effects

The banned pesticide detected in the greatest number of samples (40) is profenofos, a powerful neurotoxin belonging to the same family as sarin gas and suspected of interfering with childhood brain development. It can overstimulate the activity of the nervous system and, in farmers exposed to very high levels, cause respiratory paralysis and death.

This pesticide is marketed by Syngenta, and not on a minor scale. In 2018, the Swiss giant even exported 37 tons of profenofos from Switzerland to Brazil, where the substance is one of the pollutants most frequently detected in drinking water.

Next on this toxic podium are permethrin (detected in 34 food samples), also sold by Syngenta, and malathion (in 23 samples), two insecticides classified as probable human carcinogens by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the International Agency for research on cancer (IARC).

The OSAV data also show detections of carbofuran (in 22 samples), an insecticide banned in the European Union since 2007 (in Switzerland since 2011), notably because of concerns about the exposure of “vulnerable groups of consumers,” particularly children.

Two other substances sold by Syngenta, ametryn and diafenthiuron, are among the ten banned pesticides most frequently detected. In 2017, 125 tons of diafenthiuron were exported from Switzerland to India, Colombia and South Africa. The same year, diafenthiuron was implicated in a wave of farmer poisonings in the district of Yavatmal, in central India.

However alarming these figures may be, they do not reflect the true magnitude of the problem. Our statistics exclude pesticides like carbendazim, chlorpyrifos and chlorothalonil, which were recently banned but were still approved in 2017. Despite the regulatory action, residues can continue to be present in imported food.

Chlorothalonil – with Syngenta being one of its main producers – was banned in Switzerland at the end of 2019, as the substance is considered a “probable carcinogen” and its residues contaminate drinking water sources. Chlorpyrifos will no longer be permitted as of July 2020, due to its risks to fetal and early childhood brain development. Carbendazim, banned in 2018, has been classified as “toxic to reproduction” and “mutagenic.”

If these three pesticides are included in our calculations, the number of food samples containing banned substances jumps from 220 to 394, nearly 20 % of imported foods tested – and 30 % of imports from countries outside the European Union.

But this doesn’t seem to worry OSAV, which considers that “the detection of these pesticides shows that the monitoring system is functioning and that consumers can be protected as a result.”

“Everyone should be informed”

In the majority of cases, the concentrations are below the maximum levels set by Swiss legislation. But in 44 of the 220 samples – or one out of five cases – the values are exceeded. A pak choï cabbage from Vietnam, for example, had concentrations of permethrin at 0,98 mg/kg, whereas the maximum level for this substance is set at 0.05 mg/kg.

What happens in such a case? OSAV replies that when samples exceed the authorized levels, “the cantonal enforcement authorities impose measures and, when necessary, denounce the importers or the producers, so that they assume their responsibilities.”

Alexandre Aebi, professor and researcher in agroecology at the University of Neuchâtel, was stunned when we showed him the results of our investigation. “To find so many banned pesticides in food is frightening and everyone should be informed. All the more alarming is that we know little about the cocktail effect. The health consequences resulting from the ingestion of these mixtures of dangerous molecules should be taken seriously.”

For its part, the Swiss farmers union (USP) expressed concern “about the health of consumers and of the farmworkers involved.” The USP also denounced the “unfair competition” between Swiss-grown products that are obliged to respect strict rules and imported products grown in much laxer conditions.

For Sue Longley, General Secretary of the International Union of Food and Agricultural Workers (IUF), “Whilst of course it is of concern that food imported into Switzerland contains no less than 52 pesticides considered too dangerous to be used there,

it is also of great concern that farmworkers in the countries where the fruits and vegetables are grown are still having to work with these pesticides and risking their health and even their life to do so.”

Where do these foods come from?

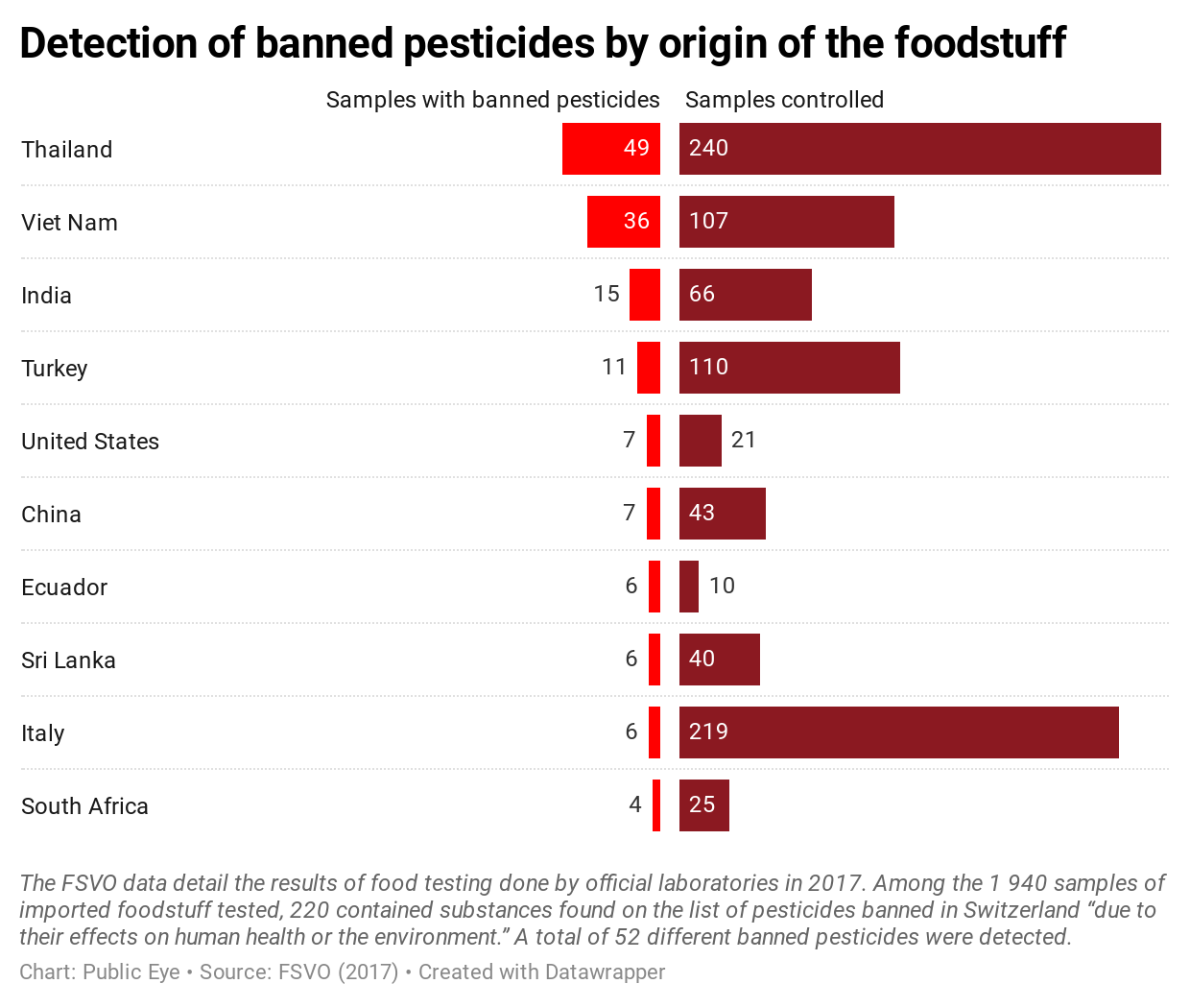

The foods most often found to contain residues of banned pesticides came from Asian countries, particularly Thailand, Vietnam and India. Almost half of the contaminated samples came from those three countries alone. But products from the three countries are also the most tested of foreign food imports, due to the identification of excessively high pesticide levels in their food imports in previous years.

The detection of banned pesticide residues is frequent: in 2017, one out of five fruit and vegetable samples from Thailand and India, and one out of three samples from Vietnam, contained them. The grand prize goes to a sample of oil seeds from Thailand that contained 15 different banned pesticides.

By comparison, relatively little sampling and testing was done of food imports from South Africa, Brazil, Columbia and Peru, which are among the principal exporters of fruits to Switzerland. And these countries are major users of highly hazardous pesticides. In all, approximately one-third of the pesticides authorized in Brazilian agriculture are prohibited by the Swiss Confederation, as pointed out in our last report.

The loopholes in the legislation

Residues of banned pesticides should not, in fact, be turning up on our dinner plates. Swiss legislation stipulates that if a pesticide is not or no longer approved in our country, the legal limit for residues in foods is set at the “limit of quantification” (0.01 mg/kg), the lowest concentration that can be reliably measured in laboratory testing.

Today that level is much lower than in the past, down to 0.005 mg/kg or even 0.001 mg/kg for many substances, as the OSAV data show. This means that foods in which residues of banned pesticides were detected at concentrations lower than 0.01 mg/kg will be considered to be fully compliant by the authorities. This is the case for two-thirds of the detections of banned pesticides in 2017.

Another problem is that OSAV can, “on request”, set an “import tolerance” higher than the “limit of quantification.” According to the law, however, this provision does not apply – i.e. an import tolerance is not allowed – if authorization of the pesticide is refused for “public health” reasons.

Yet the practice seems common. For approximately two-thirds of the 163 substances on the list of pesticides banned in Switzerland “due to their effects on human health or the environment,” a maximum residue limit higher than the limit of quantification has been set.

Examples include the import tolerances set at 3 mg/kg for residues of profenofos in hot peppers, which is 300 times the detection limit; at 0.1 mg/kg for residues of permethrin in spices, tea and coffee; and at 2 mg/kg for residues of malathion in citrus fruit. Yet the toxicity of these pesticides to health is proven.

OSAV’s response? In certain cases, “it is possible to establish import tolerances that are safe for consumers,” even if the pesticide has been banned because of health concerns. OSAV gives the example of a product that was banned because of its harmful effects on farmers in case of exposure to high doses, whereas by comparison, the consumer is only in contact with low concentration residues.

This dubious explanation not only takes liberties with the Swiss law but also ignores the health impacts on farmers and populations in the countries that produce foods for the Swiss market.

The diktat of the pesticide producers

In the majority of cases, these import tolerances were not actually established by OSAV, but by its European homologue, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and were simply transposed into Swiss law. Meanwhile, a recent investigation by the NGO Corporate Observatory Europe (CEO) has demonstrated the “immense pressures” put on the European Union (EU) by pesticide manufacturers and various trade partners, to allow residues of certain hazardous pesticides in food imports.

In an open letter published last March, a coalition of NGOs and trade unions asked the European Commission to stand up to this pressure and oppose the importation of agricultural products treated with pesticides banned in the EU. The organizations also asked the EU to put an end to the export of pesticides that have been banned because of the hazard they present.

In 2018, France showed the way by deciding to write into law a prohibition on both the marketing of foods produced with pesticides banned by European regulation and the production, storage and distribution of such pesticides. The article of the law that established this prohibition, attacked by pesticide producers, was recently validated by the Constitutional Council, which recognized in its decision that the resulting limits on free enterprise are justified in light of the “possible impacts on human health and the environment.”

The European Commission takes a stand

In a report published on 20th May, the European Commission acknowledges that the importation of foods treated with pesticides banned in the EU contradicts consumer expectations, and negatively affects the competitivity of European agriculture as well as the populations and the environment of the countries where the foods are produced.

The Commission proposes “improving clarity” of the legal provisions concerning maximum residue levels of pesticides that have been banned due to their health impacts, and says it is ready to consider revising the regulation in order to “strengthen its environmental dimension.”

The Commission has also announced that the EU will use “all its diplomacy, trade policy and development support instruments to promote the phasing out, as far as possible, of the use of pesticides no longer approved in the EU and to promote low-risk substances and alternatives to pesticides globally.”

Put an end to the double standard

This strong signal from Brussels underscores once again the need to act without delay. The Federal Council must put an end to its policy of “double standards” for hazardous pesticides, by prohibiting the export of banned substances from the Swiss territory as well as the import of such substances in the form of residues in food products.

The authorities should apply the legislation strictly with regard to pesticide residues in food, and should stop granting import tolerances for pesticides that have been banned because of their harmful health impacts. This provision should also be extended to pesticides banned for reasons of environmental protection, as the European Commission is considering.

By adopting a consistent position, Switzerland would not only strengthen the protection of Swiss consumers but would above all contribute to a better protection of farmers, populations and the environment in low- and middle-income countries, that produce foods for the Swiss market.

Switzerland would thereby send a clear signal about the need to remove highly hazardous pesticides from the market at the worldwide level.