Pesticide giants make billions from bee-harming and carcinogenic chemicals

Laurent Gaberell and Géraldine Viret, February 19, 2020

The companies’ names are BASF, Bayer, Corteva Agriscience, FMC et Syngenta. Together, these German, American and Swiss agrochemical giants control 65% of the global pesticide market, estimated at 57,6 billion U.S. dollars in 2018. United in the powerful lobby group CropLife International, which wields its considerable clout in international debates on pesticide regulation, the five companies would have us believe that their “crop protection” products make it possible to feed the world sustainably while assuring the safety of farmers, local populations and the environment.

But what exactly are the chemicals that make these companies’ fortunes? Where are they used and what are the consequences?

In April 2019, Public Eye highlighted the central role played by the Basel-based firm Syngenta in the sale of highly hazardous pesticides in developing and emerging countries.

In partnership with Unearthed, the investigative unit of Greenpeace UK, we then set out to «map» this business sector that is as lucrative as it is controversial.

Pioneering map-making

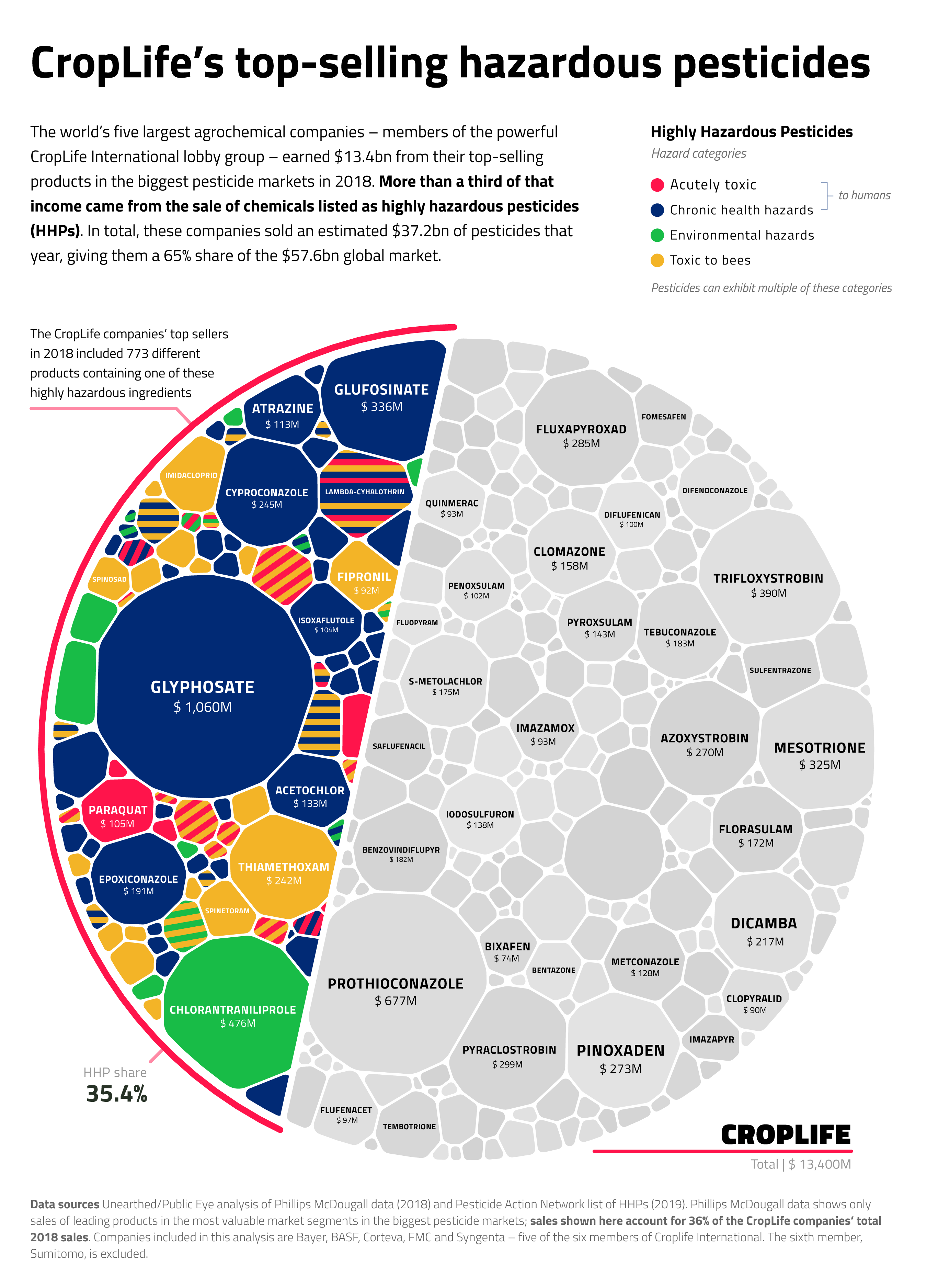

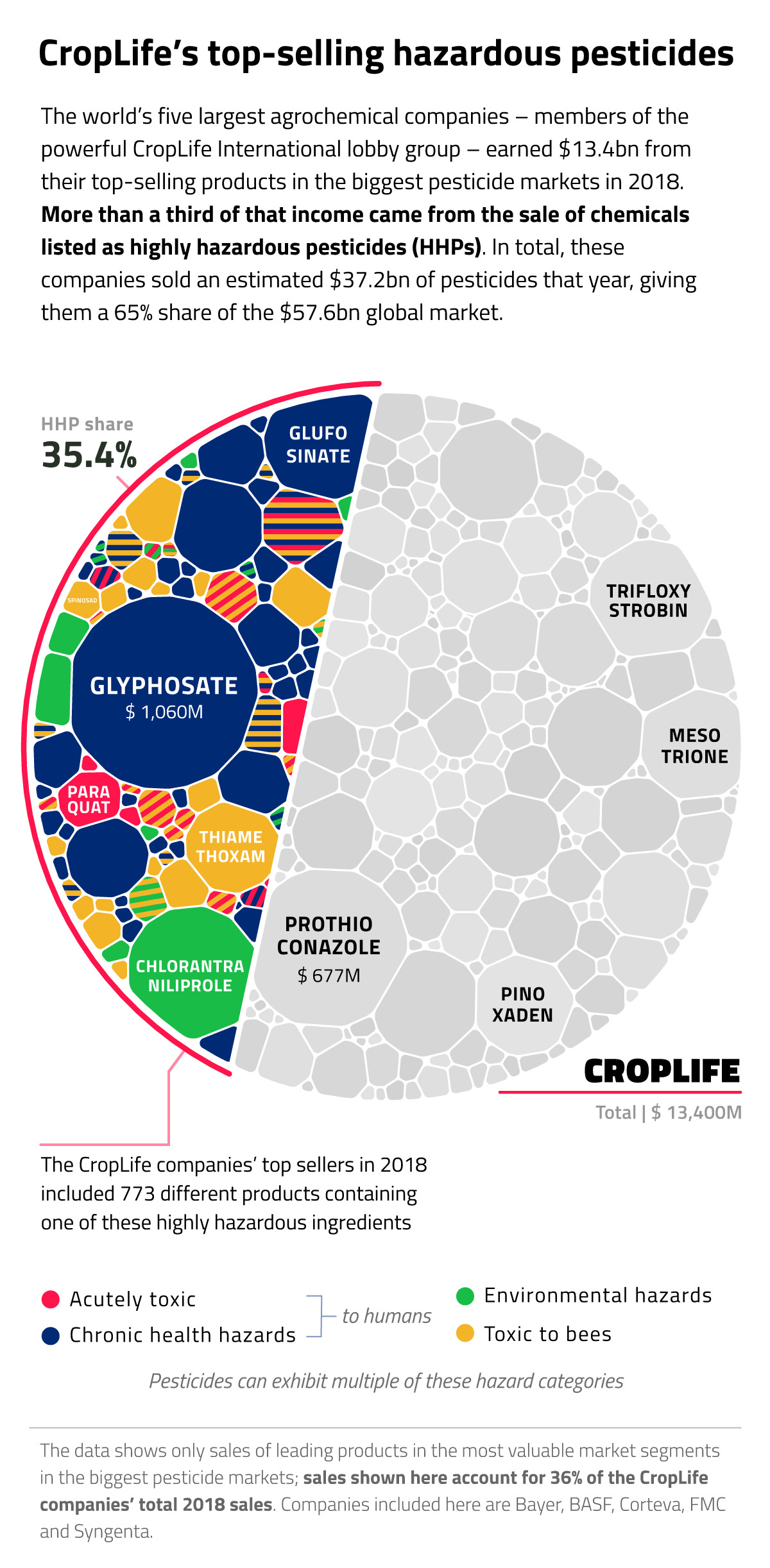

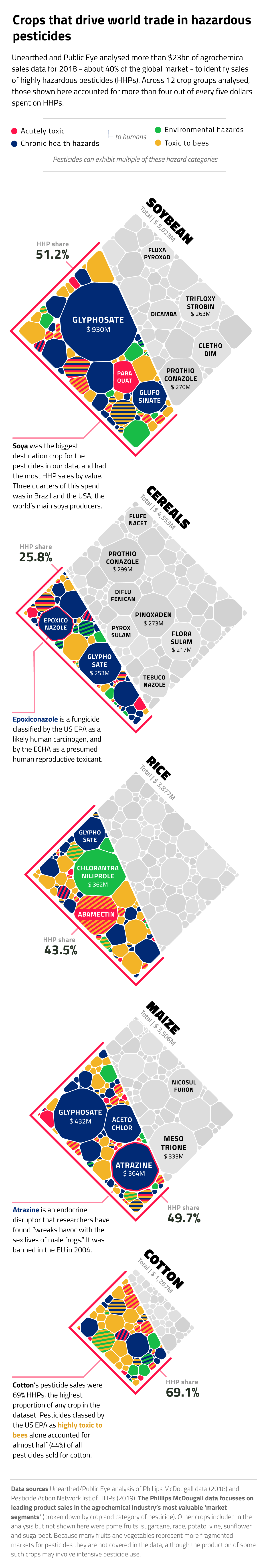

Over several months, we immersed ourselves in new data obtained from the market analysis company Philips McDougall, which detail some 23 billion dollars of agricultural pesticide sales in 2018. The data cover approximately 40% of the worldwide market for agricultural pesticides, documenting sales of the leading products in the most important markets. We analysed these data using the list of highly hazardous pesticides established by the international Pesticide Action Network (PAN), based on the assessments performed by regulators.

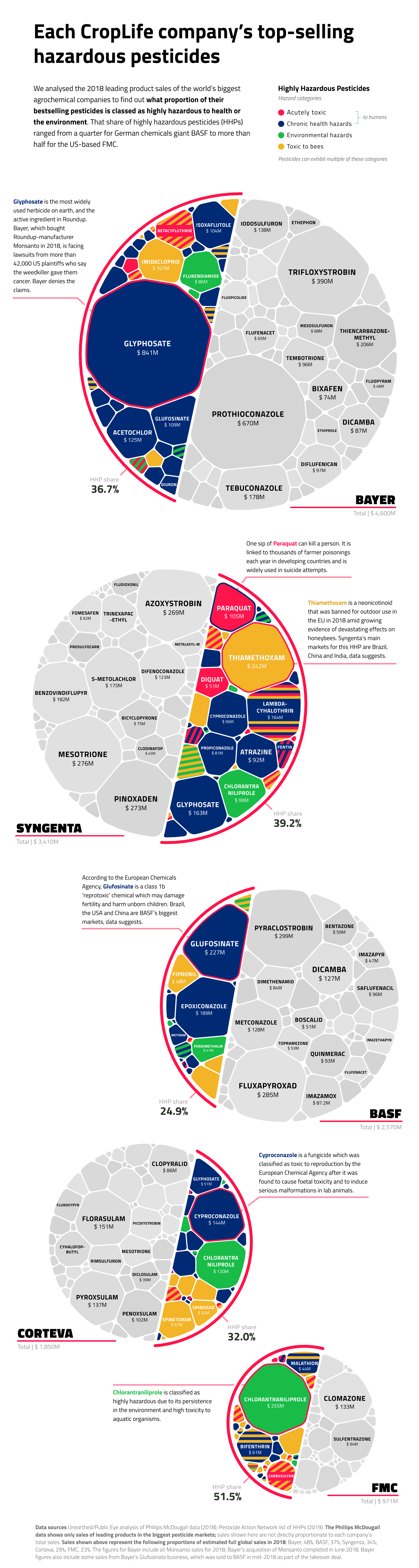

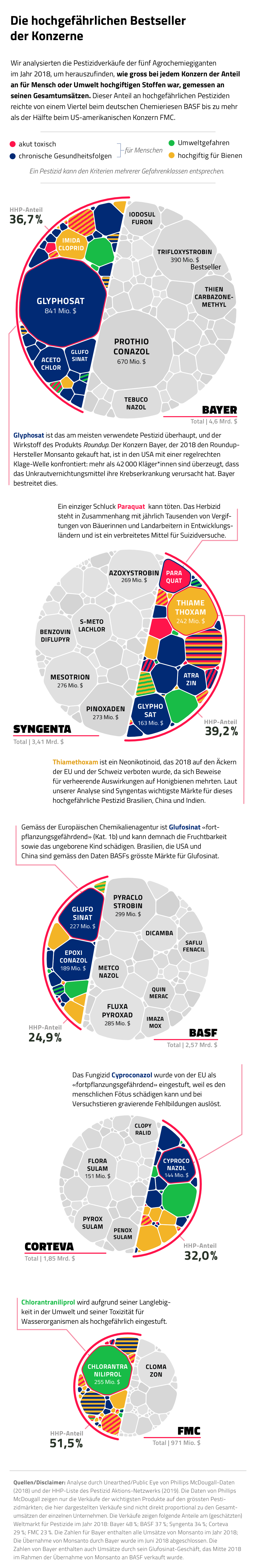

The results of our investigation are chilling. Contrary to the claims of the agribusiness lobby CropLife International, which downplays its members’ role in the trade of highly hazardous pesticides, the five most powerful companies, BASF, Bayer Crop Science, Corteva Agriscience, FMC et Syngenta, are champions in sales of the world’s most toxic and controversial pesticides. Nearly half of the companies’ “flagship products” contain substances featured on the PAN blacklist.

Our analysis of the Phillips McDougall data show that in 2018, more than a third (35%) of the pesticide sales made by these behemoths were of substances that pose the highest levels of hazard to health or the environment. Of the 13.4 billion dollars in sales made by the five agrochemical giants that are covered by the data, 4.8 billion involved pesticides classified as “extremely hazardous”.

Bayer and Syngenta lead the group in this dismal classification. And the sales figures detailed here are highly conservative, as the data cover only 40% of the worldwide market.

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

The main findings:

More infos

-

Pesticides with chronic toxicity

© Lunaé Parracho/Reuters

In 2018, BASF, Bayer, Corteva Agriscience, FMC et Syngenta made nearly a quarter of their income (22%) from selling pesticides associated with long-term health effects. The earnings amount to 3 billion dollars. At the top of the list: substances classified as probable human carcinogens and molecules that affect the reproductive system and childhood development.

-

Acutely toxic pesticides

©

Atul Loke/Panos

©

Atul Loke/Panos

The five largest agrochemical companies made 4% of their “crop protection” sales– some 600 million dollars – from pesticides that are acutely toxic to humans. Such substances cause 25 million severe farmer poisonings every year, resulting in 220 000 deaths, principally in developing countries.

-

The bee killers

©

Fabio Erdos/Panos

©

Fabio Erdos/Panos

The agrochemical giants made 10% of their income – or 1.3 billion dollars – from selling pesticides that are highly toxic to bees. These products have been identified as one of the key pressures driving a growing number of pollinator species worldwide “toward extinction”. The biggest seller of these “bee killers”: Syngenta!

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

“These results are shocking,” asserts Meriel Watts, Senior Science and Policy Advisor to PAN. “This investigation shows that there is a huge disconnect between what those companies are saying in the international policy arena and what they are actually doing.” The international agrochemical lobby repeatedly affirms, to all who will listen, that its members “are innovating to replace highly hazardous pesticides with newer, less toxic products.”

Baskut Tuncak: “The agrochemical giants have not kept their word.”

This reaction is shared by Baskut Tuncak, United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights and toxics. “The agrochemical giants have promised to phase out these highly hazardous pesticides time and time again, and failed to deliver,” Tuncak says. “The inadequate efforts of these companies betray their own repeated statements that they’re committed to sustainable development, that they are committed to respecting human rights and that they’re working towards achieving the sound management of chemicals by 2020.”

“Molecular Colonialism”

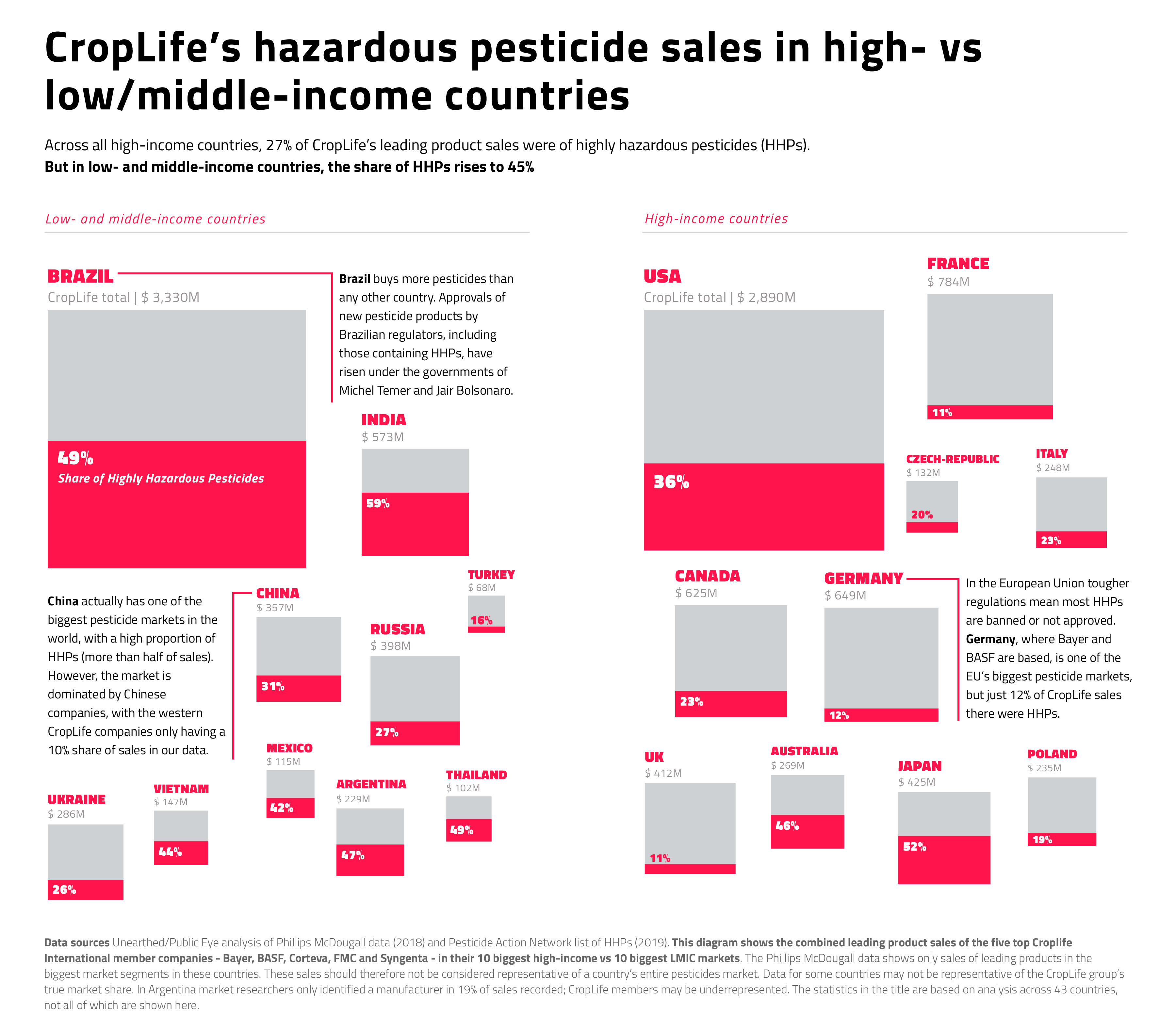

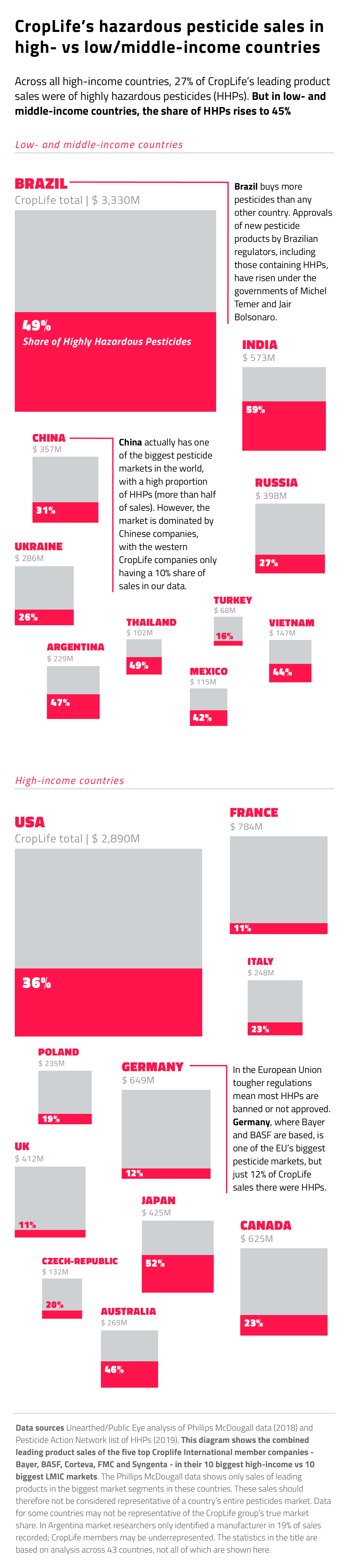

Our investigation shows that developing and emerging countries are the playing field favored by the five agrochemical giants, who make nearly 60% of their highly hazardous pesticide sales in such countries, according to the Phillips McDougall data. The data cover the 43 principal world markets, which include 21 low- and middle-income countries, mainly in South America and Asia.

The companies take advantage of the weakness of regulations in those countries to continue selling their products, despite the drastic consequences for local populations and the environment. “It’s molecular colonialism,” says Larissa Bombardi, author of an atlas of pesticides in Brazil, the world’s number one user of toxic substances.

©

Fabio Erdos / Panos

©

Fabio Erdos / Panos

In the country of Jair Bolsonaro, 49% of the sales made by Syngenta, Bayer and co. involve highly hazardous pesticides. In India, the percentage is as high as 59%. By comparison, it drops to 11% in France and 12% in Germany, the CropLife members’ two main European markets. In the European Union (EU) and Switzerland, the majority of the most toxic pesticides have been taken off the market, as a result of stricter regulations adopted over the past three decades.

The United States, a gigantic market, is the exception in this “geography” of highly hazardous pesticides. The latter make up 35% of CropLife sales in the country. “The regulatory systems are failing us in the US,” explains Jennifer Saas, of the Natural Resources Defense Council, a non-profit environmental advocacy group based in New York. “The Environmental Protection Agency is way too cosy and cooperative with the big pesticide manufacturers.”

Christopher Portier, an internationally renowned toxicologist and biostatistician, reacted to the numbers highlighted by our investigation: “I find it a little bit disturbing that the western world appears to be profiting heavily from the sales of products that they often don’t want in their own backyards.” The situation is all the more serious, he believes, because “people living in lower-income countries are going to get higher exposures and, because of this, greater risks of chronic and acute diseases.”

“This practice is dangerous and inacceptable,” says Moritz Hunsmann, researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS):

“Safe use of highly hazardous pesticides is purely and simply impossible, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

“It is disingenuous to make the argument that highly hazardous pesticides can be used safely in Brazil and other low- and middle-income countries,” affirms UN Special Rapporteur Baskut Tuncak, just back from an official visit to Brazil. “The stark reality is that Brazil, like so many other countries, has neither the governance systems nor the financial and technical capacity at present to provide a reasonable assurance they will be used safely.”

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

Chemical-greedy soybeans

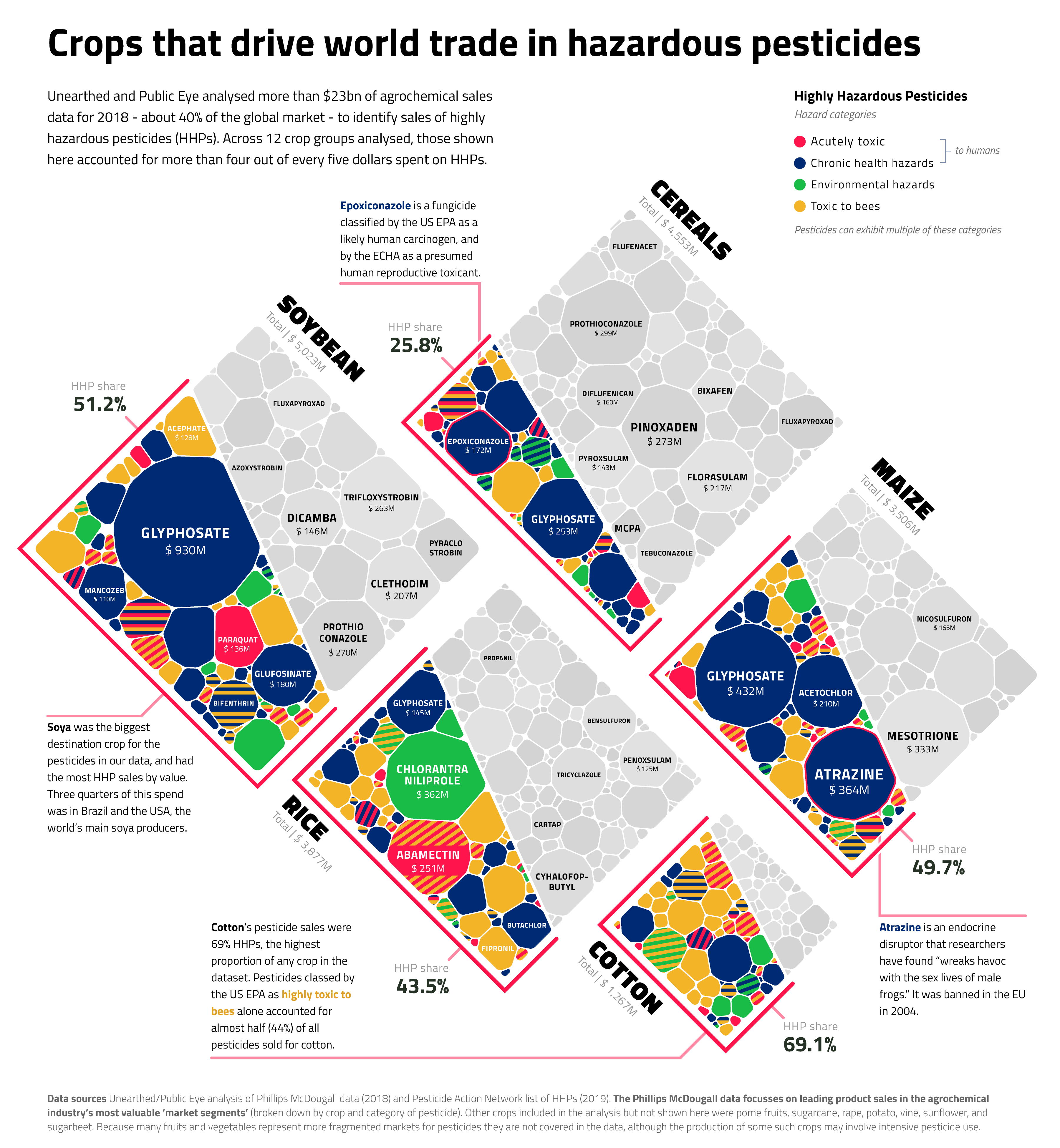

More than 80% of the CropLife members’ sales of highly hazardous pesticides identified by our investigation cover just five crops: soybeans, corn, wheat and other cereals, rice et cotton – with soybeans and corn alone representing 49% of the highly hazardous pesticide sales.

In Brazil, a significant portion of these sales (63%) is bound for the vast fields of soybeans that supply the huge global feed market. The uncontrolled expansion of monocultures that are dependent on chemical products is the cause of deforestation in the very regions that host some of the world’s most important carbon sinks and biodiversity reserves: the Amazonian rainforest and the vast Cerrado savanna.

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

©

Nadieh Bremer (Visual Cinnamon) / Unearthed / Public Eye

Detoxifying agriculture

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) recently launched a call for action to “detoxify agriculture and health from highly hazardous pesticides.“ The two United Nations agencies call for these harmful products to be replaced by safer alternatives.

“In the shadow of the existential threats of climate change and biodiversity collapse lies another, insidious extinction crisis: the toxification of our planet and our bodies,” declared Baskut Tuncak to the UN General Assembly in New York in 2019. Given the weakness of international regulations and the refusal of pesticide companies to act voluntarily, the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and toxics called on the countries that host the agrochemical giants to enact stricter rules.

CropLife’s response

Contacted for our investigation, CropLife International sent us its response. The lobby group explains, through the person of Christoph Neumann, Director of International Regulatory Affairs, Crop Protection, that it will “not comment on product specific questions or the commercial interests of [its] members.” The group rejects the PAN list and insists that its members “are committed to reducing pesticide risks by training farmers and promoting the use of personal protective equipment.”

CropLife explains that its members undertook a “voluntary portfolio review” between 2015 et 2016 in order to evaluate risks and take measures, with “a particular focus on low income countries.“ If those measures proved ineffective, the companies proceeded to voluntarily withdraw the products. CropLife refused, however, to identify the pesticides and markets concerned.

CropLife affirms that the majority of the products mentioned in our investigation are authorised in one or more member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and that it is normal for a pesticide not to be registered in certain countries “because it is not needed or uneconomic.” The industry group also notes that: “As innovation based companies, there is an interest to continuously improve the safety of our products for human health and the environment.”

Bayer sent us a long response, notably explaining that it “conducts risk assessments worldwide on its portfolio according to high standards and methodologies, and the specific agronomic realities of the countries where [it] operate[s].” All the other companies mentioned in our investigation referred us to CropLife International’s response.

A dive into the heart of the products sold by the agrochemical giants tells a different story.

Disclaimer

This text is available in three languages. In case of discrepancy between the different versions, the German text will prevail.