Conflict of Interest “Revolving doors” with the pharmaceutical industry: a major source of influence on Swiss regulatory bodies?

Patrick Durisch and Gabriela Hertig, May 22, 2025

A member of Switzerland’s Federal Council who, as soon as his term of office was over, joined a leading construction company that previously reported to him as the supervising minister; a State Secretary for Economic Affairs (SECO) who, less than a year after leaving her official post, joined the Board of Directors of Nestlé – a multinational whose commercial interests she defended as Switzerland’s ambassador and chief negotiator with international bodies; and a vice-director of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), in charge of the Health and Accident Insurance Directorate, who immediately after leaving became the new CEO of a private health insurance company. News about senior officials or members of the government moving into the private sector occasionally make headlines, raising legitimate concerns about potential conflicts of interest and the authorities’ independence.

So, is this “revolving doors” practice marginal or, on the contrary, well established? Does it only involve senior executives? Or any level in the hierarchy? And what about the “reverse revolving doors”, a move from the private sector to the public sector, which comes under less scrutiny but is just as likely to tighten the grip of companies on political processes and structures, known as “corporate capture”?

To answer these questions, we joined forces with the WAV research group to conduct an unprecedented investigation in Switzerland. The aim was to identify cases involving this “revolving doors” practice in the pharmaceutical sector, i.e. moves between this industry – a sector whose political influence and powerful lobbying has been widely documented – and two federal offices in charge of regulating medicines policy: Swissmedic and the FOPH (our methodology is described at the bottom of this page).

Many revolving doors between pharma and its regulators

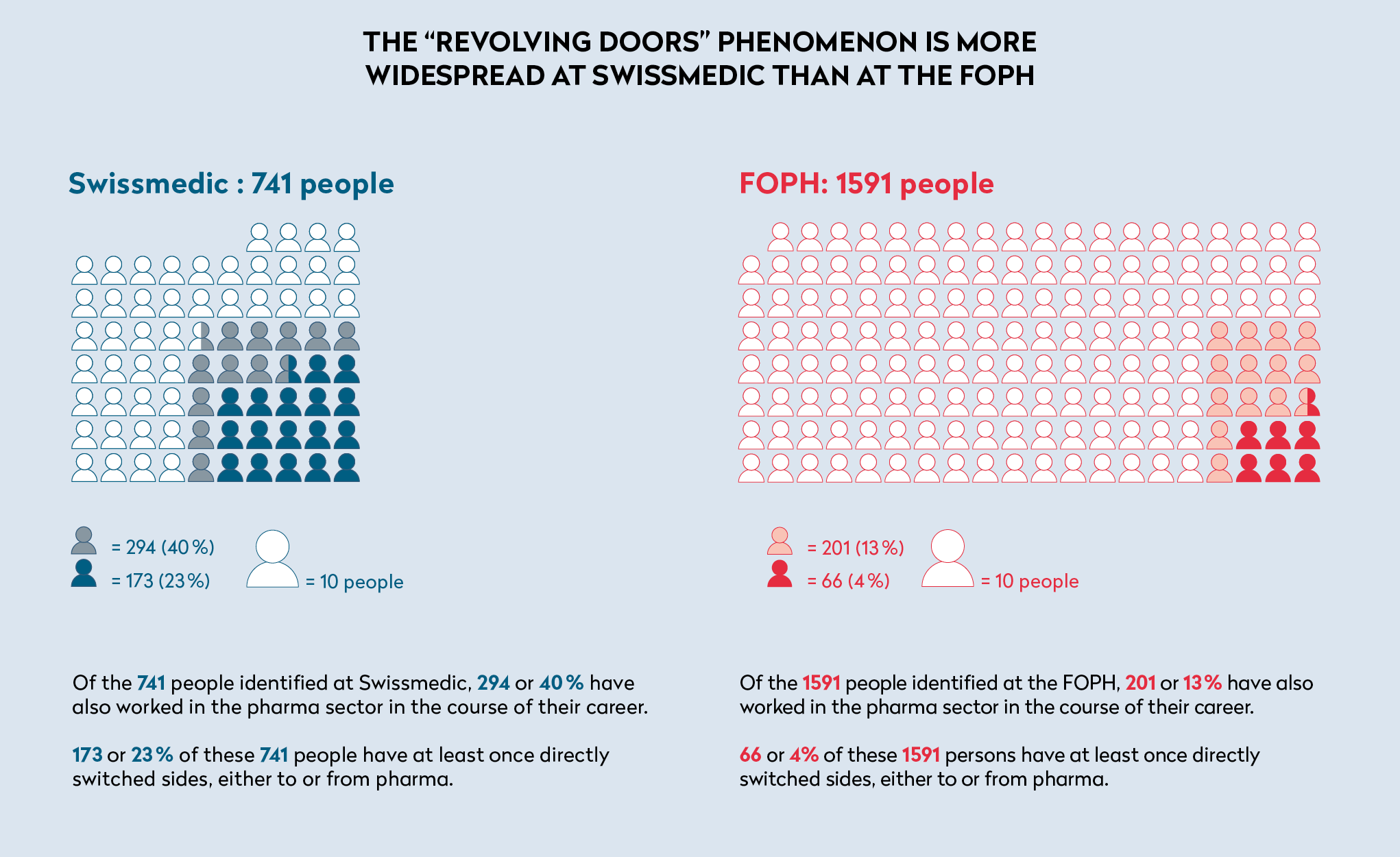

Our investigation identified 239 people involved in at least one instance of “revolving doors” with the pharmaceutical sector - 173 from Swissmedic, and 66 from the FOPH. (See graph below).

More broadly, of the 741 people we identified as having worked at Swissmedic, 294 had worked for at least one pharmaceuticals company – i.e. almost 40 percent, with all functions combined. In the case of the FOPH, whose public-health mission extends far beyond medicine policy, this rate was 13 percent (201 out of 1,591).

Of the 239 people who, in total, have been practicing with “revolving doors” in the pharmaceutical sector, 43 (or 18 percent) have repeated it during their career. For example, one person who, after five years in charge of regulatory affairs in the pharmaceutical industry, worked for 18 months at Swissmedic as an examiner of approval documents, then spent 17 years in various large pharmaceutical companies (including Novartis) as well as a consulting firm in the same field, before taking up a similar position at the institute again for a year and a half, finally returning to the same legal firm.

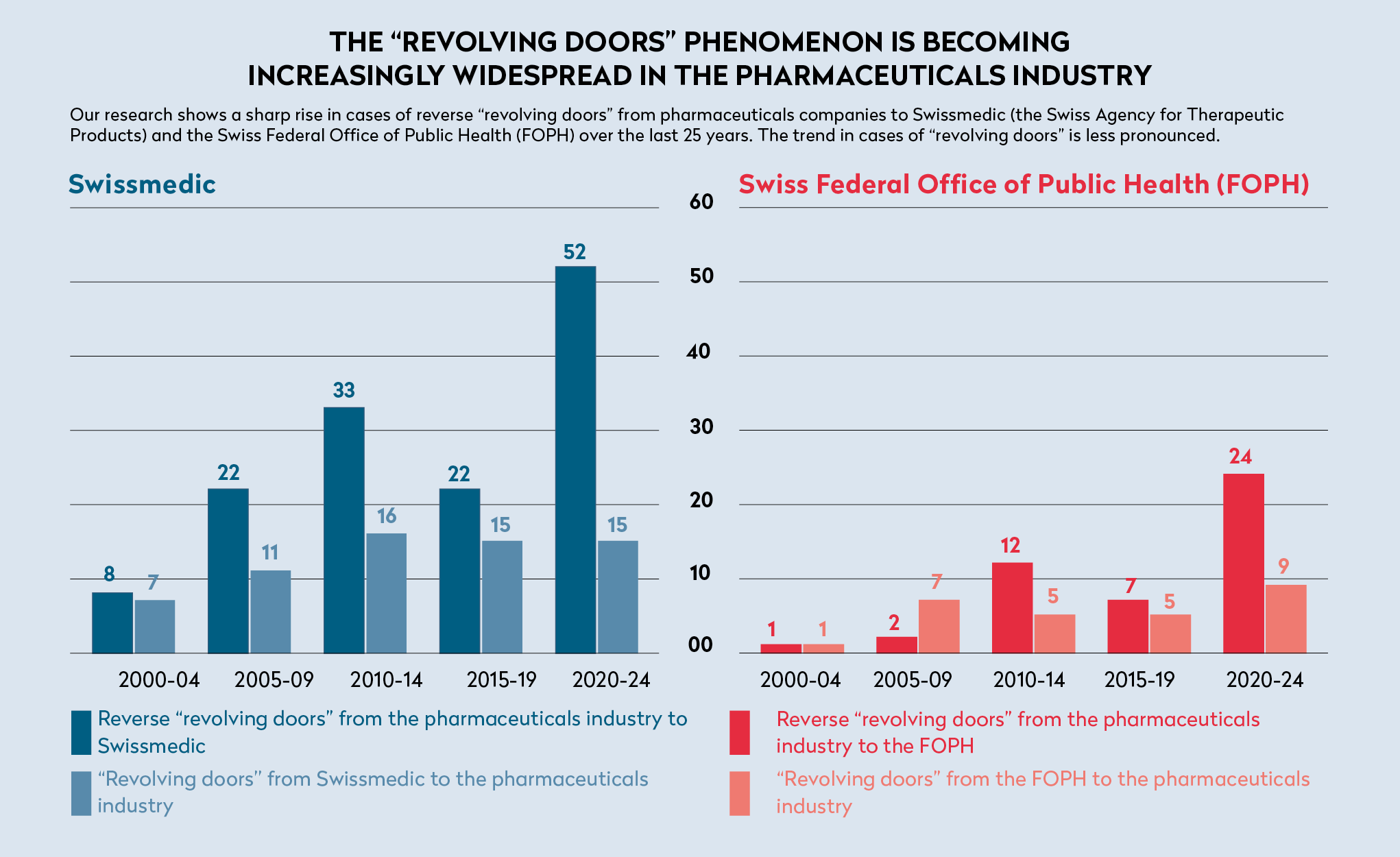

In total, our investigation identified 208 “revolving doors” instances in the pharmaceutical industry involving Swissmedic and 76 involving the FOPH. The chart below shows a sharp increase in the less well-documented phenomenon of reverse revolving doors over the last 25 years. At 189 out of 284, these changes from the private to the public sector account for two thirds of all cases.

Part of this rise can be explained by an increased use of the LinkedIn network, which makes it easier to identify such cases. However, it does not explain the drop in private public reverse revolving doors cases observed during the period 2015 to 2019, followed by a dramatic increase over the last five years. An increase has also been seen in the number of direct moves from the pharmaceutical industry to Swissmedic ad the FOPH.

This “revolving doors” practice has been seen at every level of the hierarchy. Of the 239 people involved in the “revolving doors” practice with the pharma sector on one or more occasions:

- 26 (11 percent) were or are members of the directorate or senior executives

- 204 (85 percent) held or currently hold positions not appearing in the official organigram (heads of units, scientific experts, inspectors, legal counsel, etc.)

- 9 (4 percent) were or are experts commissioned by the associated federal offices. These people, who are also subject to provisions preventing conflicts of interest, issue opinions as part of the decision-making process (e.g. on the approval or pricing of medical products) or are members of extra-parliamentary committees whose subject matter is directly related to the activities carried out by Swissmedic or the FOPH.

Key areas exposed to the “revolving doors” issue

Some areas of activity in the pharmaceutical sector are more exposed than others to the “revolving doors” practice. For those in favour of executives moving movements from the private to the public sector, this is justified by the in-depth expertise gained that is required to examine approval documents and perform market surveillance, and which could only be acquired in the pharmaceutical sector. This argument trivializes the risk of conflicts of interest and ignores the expertise of the academic and medical communities.

The commercial stakes surrounding the regulation of medicines provide another explanation, as highlighted by the intense lobbying of the pharmaceutical industry to remove regulatory barriers. Our investigation identifies several key sectors relating to the regulation of medicines, which are particularly prone to the revolving doors practice:

- Swissmedic’s Marketing Authorisation (MA) sector, with 90 persons (52 percent of those involved in revolving doors between pharma and the Swiss medicines agency).

One example is a person who was appointed as head of this sector at Swissmedic after more than nine years as an advisor and medical director in big pharma. Or the executive who, after working for 18 years in various pharmaceutical companies (including Sandoz and Roche) became head of this sector at Swissmedic, before moving on to Novartis as head of compliance.

The granting of a marketing approval is a critical step for the industry, as it conditions the marketing of a drug, and thus the revenue stream. Any delay in getting this authorisation can mean a loss of several millions Swiss francs for the manufacturer. That is why pharma is pushing hard for fast-tracked approvals, which are on the rise.

The Licences & Supervision sector – comprising “Clinical Trials”, “Inspections” and “Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products” (ATMPs) divisions – with 52 persons (30 percent).

One example shows an analyst who was in charge of clinical trials for 15 years in various pharmaceutical companies (including Novartis) and who then joined the Swissmedic division as a scientist, where he stayed for more than two years, before returning to big pharma as associate director. Another person who, after working for 15 years in various pharmaceutical companies, is now in charge of the regulation of ATMPs at Swissmedic.

Clinical trials are a mandatory step in the process of proving the efficacy and safety of a new medicine so that it can obtain a market approval. A problem identified during an inspection, or data judged not to be robust enough can be costly. ATMPs include cell therapies (such as Novartis’ cancer drug Kymriah) and gene therapies, a fast-growing field with a still recent regulatory system.

The Health and Accident Insurance Directorate – including the “Medicines” division – with 30 people (45 percent of those involved in revolving doors between pharma and the FOPH).

For instance, a pharmacist with 10 years working at a large pharmaceutical company as a regulatory affairs expert, who joined the “Medicines” division of the FOPH for a year and a half, before going to one of the world leaders in biotechnology. Then there was a former head of this directorate – also vice-director of the FOPH – who, after completing his term of office, set up his own law firm, offering advice to pharmaceutical companies on regulatory matters.

Setting the price of medicines is a key step for the sector because the tariffs decided by the FOPH directly affect its profit margins.

Our investigation also identified “revolving doors” instances in other relevant areas, such as the legislation on therapeutic products and research on human beings (FOPH), communicable diseases (especially during the Covid pandemic, FOPH), access to patient data (FOPH) and harmonization of the regulatory standards of medicines (Swissmedic).

When asked, Swissmedic and the FOPH replied that they were aware of the risks of conflicts of interest in connection with switching sides, but did not comment on the results of our survey and stated that they do not have statistics on this topic.

Swissmedic emphasises that decisions on authorisations or inspections are made as a team involving various hierarchical levels. In addition, managers must reaffirm their compliance with the Code of Conduct annually and other employees every two years. Swissmedic does not provide any information on our questions regarding the application of measures in the event of lateral transfers revolving doors and refers to the existing legal provisions (see below), which should apply to all staff. The authority states that it has improved its regulations following an audit by the Swiss Federal Audit Office in 2020. And it points out to be relying on the knowledge of people from the pharmaceutical industry to fulfil its tasks. Conversely, from their perspective, it helps the is a “relief” for the pharmaceutical industry to have people at regulatory authorities who understand their point of view

The FOPH points out that people with a professional expertise and in-depth knowledge of the Swiss healthcare system are ‘particularly in demand’ and necessary for its role. Rules like a binding code of conduct and the applicable legal provisions minimise conflicts of interest. However, the authority does not provide any details about their practical implementation. The Federal Office also stresses that the existing rules apply to all types of lateral moves revolving doors, including those from the private sector to the public sector, but grace cooling-off periods are only provided for management positions.

Insufficient and vague measures

This “revolving doors” issue is not new. The risks it entails in terms of conflicts of interest, corporate capture, corruption, and loss of trust with regard to the authorities – not to mention distortion of competition – have been known for a long time.

“In our country, job changes between the administration and the private sector are relatively common,” says Urs Thalmann, Managing Director of Transparency International Switzerland. “Even though such transfers may be in the public interest, the dangers of bias, illegitimate access to information and influence peddling are very real.” In his view, these risks should be countered by proportionate, clear and consistently applied rules, such as waiting cooling-off periods, particularly for transfers between regulatory authorities and the companies they supervise.

However, Switzerland has been slow in implementing general measures aimed at minimizing the risks associated with “revolving doors”. It was not until an evaluation in 2007 by the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), recommended that this practice should be regulated, that Switzerland’s Federal Council called in late 2008 for an Interdepartmental Working Group on the Fight against Corruption (Corruption IDWG) to be set up. More recently, an anti-corruption strategy for 2021-2024 was adopted, which is expected to be updated shortly.

The first legislative measures to regulate this issue include the duty to maintain business secrecy, a recusal in the event of bias, the possibility of a waiting or “cooling-off” period for certain categories of staff – i.e. a minimum period of time between ending a job in the public sector and taking up a new position in the private sector – and the appointment to another less exposed position in the event of conflicts of interest. As a decentralized federal administration, Swissmedic has its own implementation rules in this area, which make no explicit reference to any cooling-off period (see below).

More infos

-

“Revolving doors” regulation in Switzerland

In the 2000s, Switzerland signed up to several international conventions aimed at combating corruption – an area that overlaps with the illegal acquisition of interests, including the practice of revolving doors – such as the Anti-Bribery Convention of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2000), the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption of the Council of Europe (2006), which established the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), and the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC, 2009).

However, Switzerland has been slow in implementing specific measures aimed at minimizing the risks associated with the “revolving doors” practice. It was not until an evaluation was performed by GRECO in 2007, highlighting the shortcomings of Swiss legislation in this area and recommending in particular that the “revolving doors” practice should be regulated, that Switzerland’s Federal Council called in late 2008 for an Interdepartmental Working Group on the Fight against Corruption (Corruption IDWG). More recently, the Federal Council adopted an anti-corruption strategy for 2021-2024, which is expected to be renewed shortly for the period 2025–2028.

A series of measures for a better regulation of the “revolving doors” practice among employees of the central federal administration (FOPH and SECO) features in the Federal Act on the Personnel of the Swiss Confederation (FPA) (LPers, SR 172.220.1) and its ordinance. These include:

A duty to maintain secrecy about service matters, including after termination of the employment relationship (Article 22 FPA/Article 94 of the Federal Personnel Ordinance (FPersO)) – the Criminal Code also includes a provision concerning the breach of official secrecy (Article 320 CC);

Recusal in the event of a risk of bias (Article 20 FPA/Article 94a FPersO);

The possibility to introduce a waiting or cooling-off period of six to twelve months for certain categories of staff (mainly very senior executives) after termination of the employment relationship (Article 94b FPersO);

- A ban on employees using non-public information which they have become aware of while carrying out their function (Article 20 FPA/Article 94c FPersO).

The Confederation has also issued a Code of Conduct, with its revised 2024 version containing some of these points, but it is not binding and only applies to staff of the central federal administration (FOPH in particular).

As a decentralized federal administration, Swissmedic has its own implementation rules in this area. They can be found in the Ordinance on the Personnel of the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (SR 812.215.4) and the Swissmedic Code of Conduct (which is binding as it is an integral part of the employment contract), which apply to both staff and experts commissioned by the Institute.

In addition to a duty of care and fidelity (Article 43), the duty to maintain official/professional/ business secrecy (Article 45), the duty to authorise obtain an authorisation for any ancillary activity (Article 46) and the duty to recuse in the event of a conflict of interest (Article 48), the ordinance also imposes the duty on employees to announce any departure to a pharmaceuticals company and provides for the option of taking measures (recusal, assignment to another function or release from functions) aimed at avoiding conflicts of interest (Article 44). This point is included in the Code of Conduct (Article 18), specifying that these measures are particularly relevant to “the Director, as well as members of the Executive Board and employees who have a decisive influence on important decisions in the context of authorizations and controls”. However, there is no explicit mention of a waiting period.

The waiting period comes under a specific ordinance that came into force in 2016 (Ordinance on Waiting Period, SR 172.010.1). This defines the rules applicable in this area to executives at the highest level of the federal administration, to members of the governing bodies of federal institutions and to members of extra-parliamentary committees.

However, some of these measures, such as the cooling-off period, are not sufficient to counter the “revolving doors” practice effectively and the conflicts of interest arising from it, as recently confirmed by GRECO (2024) and an audit by the Swiss Federal Audit Office (2025).

Public Eye recommends the following points to tighten regulation of the revolving door phenomenon and ensure the primacy of public interest over professional lateral moves:

- A cooling-off period, which is currently “possible”, should be more systematic. In 2011, the Corruption IDWG recommended the introduction of an “anti-revolving door” clause with a cooling-off period to be included in the employment contracts of senior executives. Nothing has come of this so far. A questionnaire sent in 2019 to the secretariat general of the seven departments showed that such a clause had only been included three times since 2016. The Federal Council and the Corruption IDWG are reluctant to call for a broader, systematic application of the cooling-off period, on the pretext of protecting the economic freedom of the persons concerned.

- The cooling-off period should have a minimum duration of 12 months. This view is shared by the UN and GRECO. The maximum duration in Switzerland of 6 to 12 months remains well below that of many European countries, which provide cooling-off periods of up to 36 months, at least for senior administrative officials. Transparency International also recommends 12-18 months as a “reasonable minimum” duration.

- The colling-off period should be applied more widely. Currently, it mainly targets secretaries of state, office directors and secretaries-general of departments, as well as their deputies. Members of the management board at Swissmedic or the FOPH other than the director who might decide to switch to the pharmaceutical sector are not affected, even though such moves may risk a conflict of interest and damage the reputation of the federal administration. Lower positions in the hierarchy are not subject to this at all, although some may also put the commercial interests of the pharmaceuticals industry before the public interest.

- The move from the private to the public sector should also be taken into account in relation to regulation and control measures. The focus is currently on moves from the public to the private sector. However, our investigation has identified twice as many cases of “reverse revolving doors” from the pharmaceutical sector. There is indeed a duty on people to recuse themselves, but this depends on the degree of transparency regarding the conflicts of interest declared by the employee, based on a personal assessment. A more systematic review would make it easier to identify risks. A more formal ban on performing certain public administration functions – as exists in France and Italy, for example, under their legislation – should also be considered.

- Concrete cases of “revolving doors” should be handled openly. The current lack of transparency makes it impossible to know whether measures are being taken to tackle this issue, and to what extent. In a 2018 report, for example, the Swiss Federal Audit Office found that a “revolving doors” clause has been incorporated into the Confederation’s human resources legislation, but that it “is not implemented”. Greater transparency around the practice of revolving doors in Switzerland “as a basic democratic measure” was also the subject of a call for a motion in the National Council in 2023 following the former head of SECO’s move to Nestlé.

Authorities must take action

Our investigation shows that the practice of “revolving doors” between pharma and public bodies in charge of regulating the medicines market is very common in Switzerland. This closeness raises legitimate concerns about the independence of our regulatory authorities, particularly when such staff moves are not adequately supervised. The fact that around 80 percent of Swissmedic’s budget comes from the pharmaceuticals industry, already raises suspicions of bias.

Not all cases of “revolving doors” entail the same risks. It would therefore not make sense to ban this practice, also for constitutional reasons regarding people’s economic freedom. Some moves from the private to the public sector in this industry may even be beneficial when expertise is transferred, as long as sound measures avoid the risk of conflict of interest or of exerting influence.

But today, it’s impossible to know whether the control measures provided by the law are really applied, and to what extent. Greater transparency is required to preserve the trust of the public in the authorities. Measures aimed only at raising awareness, as envisaged by the anti-corruption strategy, will not be sufficient. The Federal authorities must actively inform about their concrete steps of implementation.

If the “revolving doors” issue is not adequately adressed and regulated, an entity like Swissmedic risks becoming an economic promoter for the industry rather than a regulatory agency operating in the public interest.

More infos

-

Methodology

Public Eye commissioned the WAV research group to collect relevant data to identify cases of the revolving doors or reverse revolving doors practice involving moves between the pharmaceutical industry and three federal offices involved in regulating medicines policy: Swissmedic, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) and the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO).*

By means of a “Premium Business” account on LinkedIn, WAV manually established a list of people who had indicated Swissmedic, the FOPH or SECO as their current or former employer in their profile (as of 01.08.2024), along with their professional background.

WAV then completed this list using three other sources:

- The Federal Directory (www.staatskalender.admin.ch) with its data on current staff of the federal administration.

- The organigrams of the last ten years (2013–2024), requested by Public Eye from the three associated federal offices.

- A supplementary web search to obtain career details of people without a LinkedIn profile.

This resulted all the information collected was compiled manually in a database which includes 3,118 people with details of their professional background*

Public Eye analysed this database to identify the cases of “revolving doors” with pharma, based on the following criteria:

- The person must have worked for at least one year in a pharmaceutical company and at least one year in the associated federal office.

- The move from one to the other must have been direct.

- “Pharma” means companies: (1) involved in the R&D, production and marketing of commercial medicines; (2) members of an umbrella association representing the commercial interests of the relevant companies (e.g. Interpharma or Intergenerika); and (3) offering advice and services in the field of pharmaceutical law, R&D or regulatory affairs.

All direct moves to or from health insurance companies, distribution entities (pharmacies, wholesalers), analysis/diagnostic laboratories, companies specializing in medical devices, veterinary medicines, complementary/natural medicine, food supplements and cosmetics are not considered as cases of revolving doors with pharma.

*Due to SECO’s multi-sectoral mandate and the low relevance of the results (five cases of “revolving doors” with pharma), they were not included in the analysis.

This investigation is based in particular on data from LinkedIn profiles, which are self-declarations and may not be up to date. These limitations have been mitigated by cross-referencing some of the information with other sources.