Risky Business for Swiss Commodity Trade Russian Grain Plundering in Ukraine

Silvie Lang, Thomas Braunschweig, Robert Bachmann, February 13, 2024

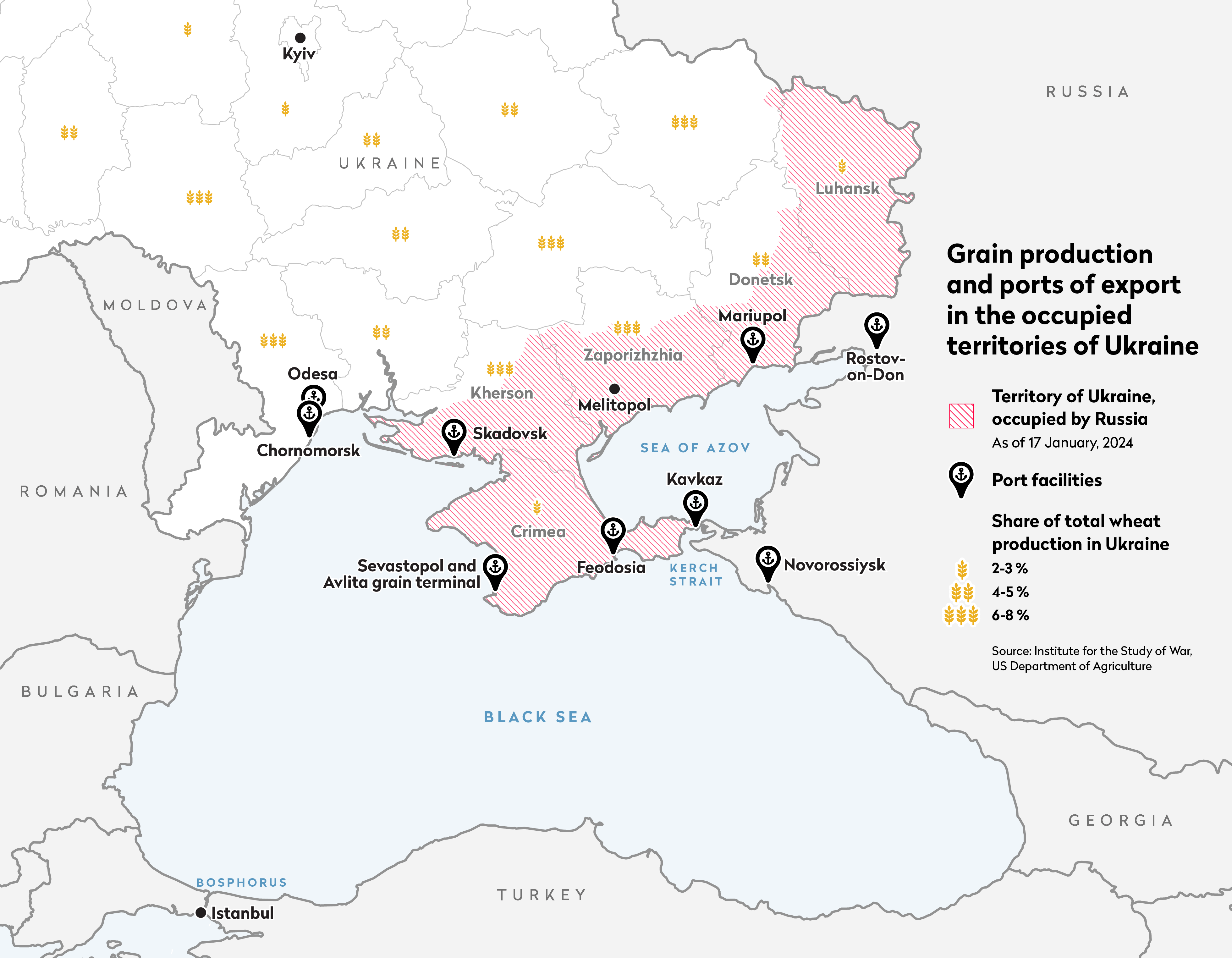

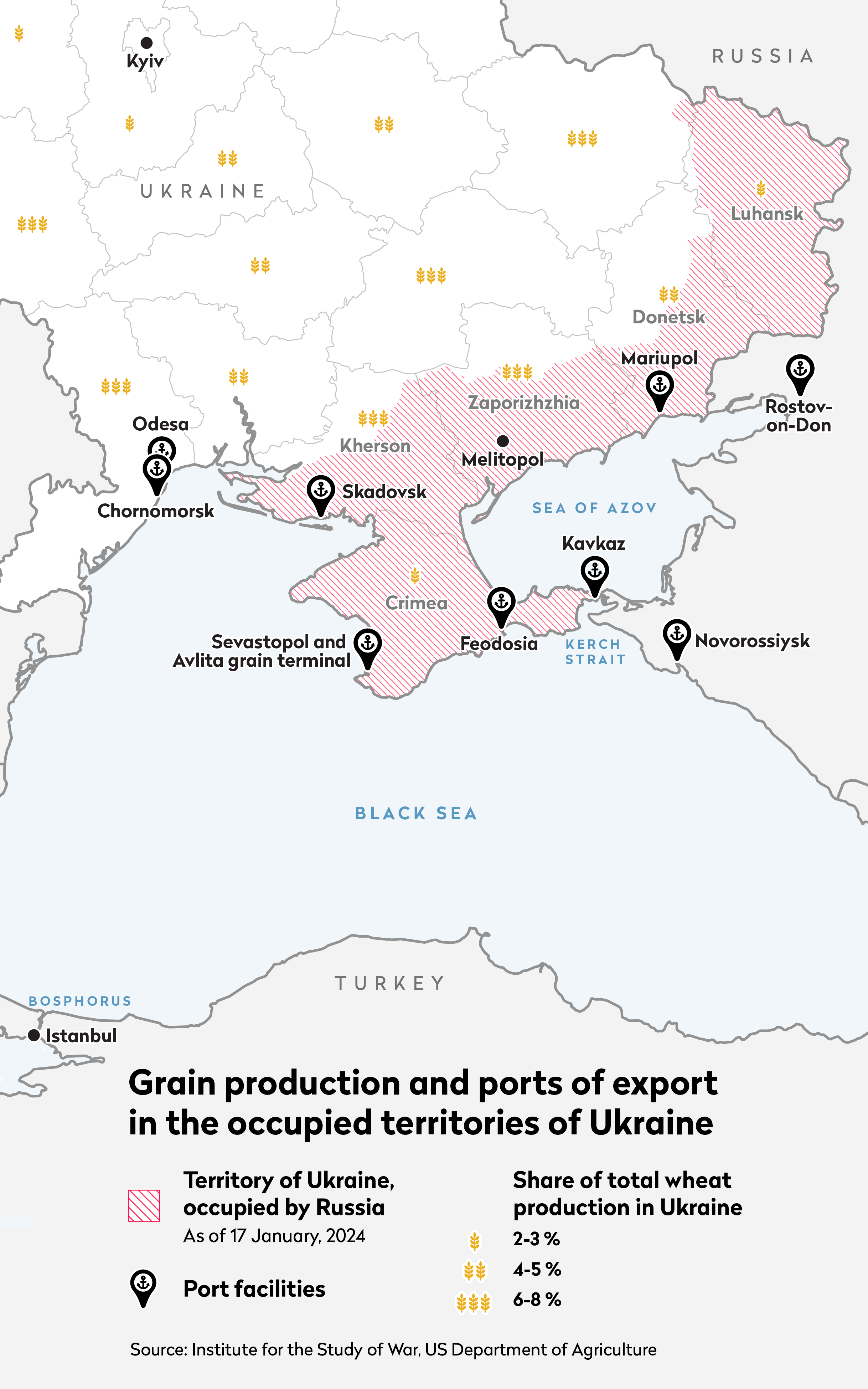

Ukraine is commonly referred to as 'the breadbasket of Europe'. According to trade databases, prior to the Russian invasion, the country accounted for nearly 10% of global wheat exports, 13% of global corn exports, and 40% of all sunflower oil traded. Thanks to its fertile black soil, the south-east of Ukraine is particularly crucial for the cultivation of grain. Part of this region has been under Russian occupation since 2014.

Particularly since the beginning of the war in 2022 and the expansion of the occupied Ukrainian territories in particular, the Russian government has been operating a highly organised system for controlling local agricultural production and the export of agricultural goods. A central part of this is the systematic and sometimes violent theft of grain and the appropriation of infrastructure. Under international humanitarian law, such appropriations by an occupying power principally constitute an act of plunder and are therefore prohibited.

Large-scale grain theft

Shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, reports about the theft of grain by the Russian occupying forces appeared in international media. By the beginning of May 2022, over 500,000 tons of grain worth more than 100 million US dollars had already been stolen by Russian entities. By the end of 2022, according to Bloomberg, it amounted to nearly 6 million tons of wheat, which meant Ukraine had been deprived of at least 1 billion US dollars in revenue.

©

Keystone/AP

©

Keystone/AP

As well as appropriating crops, the Russian occupiers also took over entire grain storage facilities and farms.

To organise this plunder, the Russian government set up state-owned and municipal enterprises in the occupied Ukrainian territories - under Russian law.

Especially in the almost entirely occupied regions of Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia, in the spring of 2022 the newly established State Grain Operator GZO (Gosudarstvennyj Zernovoy Operator) took control of road and rail networks as well as port facilities required for grain exports. As the local infrastructure is currently completely in Russian hands, Russia presumably has comprehensive control over the grain trade in the occupied regions.

In June 2023, the Russian state news agency TASS reported very openly about GZO's business. The company reportedly exported 250,000 tons of grain from the occupied Ukrainian region of Zaporizhzhia in the first quarter of 2023, mainly to Turkey and Egypt. For the entire year of 2023, the objective was to export over 1.5 million tonnes from this region alone. A comprehensive analysis by an international law firm has come to the conclusion that GZO plays a central role in the procurement, storage and transportation of grain in the Russian-occupied territories. The US, the UK and Ukraine have sanctioned the company for this activity.

Plundered grain entering the world market

The plundered grain ends up on the world market via several routes. On the one hand, it is transported by road and rail – often via Melitopol - to the ports of Sevastopol or Feodosia on the occupied Crimean peninsula and from there, to Russia or directly to third countries. On the other hand, it is moved via the occupied port of Mariupol to Sevastopol or to Rostov-on-Don in Russia. Moreover, the Russian occupiers have expanded the port in Skadovsk (Kherson) in order to increase the export of grain to Russian ports from there.

©

Public Eye / Fabian Lang

©

Public Eye / Fabian Lang

©

Public Eye / Fabian Lang

©

Public Eye / Fabian Lang

The export volume from the Crimean ports gives an idea of the extent of the systematic plunder. According to Bloomberg, grain exports from the peninsula have increased 50-fold compared to the period before the invasion in February 2022. In our research, we came across reports of around fifty shipments of Ukrainian grain from these occupied ports between March 2022 and October 2023.

Meanwhile, in the Ukrainian regions which are not occupied by Russia, the Russian army is trying to destroy agricultural production and export infrastructure. Since Russia's withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative in July 2023, Russian bombing has once again increased significantly in terms of both intensity and frequency. On 19 July 2023, Russia withdrew security guarantees for ships in the north-western part of the Black Sea, while the Russian Ministry of Defence declared that all ships calling at Ukrainian ports would be considered potential carriers of military cargo. Moreover, as part of the strategy, it began targeted attacks on two of the three Ukrainian ports that were used as export channels under the initiative: Odesa and Chornomorsk. Port infrastructure and grain terminals were bombed and an estimated 60,000 tons of grain were destroyed.

©

Sopa Images/Alamy

©

Sopa Images/Alamy

Ukrainian grain becomes Russian grain

Various methods are employed to disguise the true origin of the plundered grain. For example, the grain is transported to Russia and mixed with Russian grain in their Black Sea ports. Another strategy uses so-called ship to ship transfers. Research by the BBC, the Associated Press and investigative collective Bellingcat demonstrated that Ukrainian grain is loaded onto small Russian ships in Crimean ports and transferred onto large bulk carriers off the Russian coast, especially in the Kerch Strait.

For this purpose, the preferred location seems to be a certain anchorage outside the port of Kavkaz. According to a Russian grain exporter, this has been used for years to conceal the export of Ukrainian grain from Crimea. This is also where stolen grain is mixed with grain from Russia and subsequently sold as Russian grain. The larger ships then transport these cargoes to Egypt, Libya, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, Syria, or Turkey, in particular.

Ghost ships without a radio signal

Another popular concealment method is switching off the radio transponder (AIS; Automatic Information System) of grain carriers, which then no longer transmit their position data. Associated Press was able to prove, through satellite images, that during the first six months of the war, three dozen ships carried out grain shipments from Russian-occupied territories to Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, or other countries while their AIS was temporarily deactivated.

©

Olga Volodina/Alamy

©

Olga Volodina/Alamy

Using satellite images, Bellingcat was able to demonstrate that ships with their AIS switched off had docked at the Avlita grain terminal at Sevastopol on at least 179 days during the first twelve months of Russia's war. This was intended to cover up the loading of stolen grain.

The systematic theft of grain is part of a comprehensive Russian plan.

The aim is to deprive Ukraine of crucial export revenue and for the source of food – vital for many import-dependent countries in the Middle East, parts of Africa and Asia – to become a weapon of war. The three-stage system of plunder includes

- control of grain storage, road, rail, and port infrastructure,

- transportation from the occupied territories within Ukraine and then cross-border to Russia or other countries – covering up the origin of the grain as far as possible – and

- the destruction of Ukrainian grain infrastructure and ports.

Pillage is prohibited under international law

International law sets clear rules for the violent appropriation of the property of the civilian population of occupied territories by an invading or conquering army. Such acts are defined as pillage (or plunder) and are, with a few exceptions, prohibited.

International humanitarian law applies in international armed conflicts, such as the war in Ukraine, and classifies pillage as a war crime. Moreover, the Rome Statute, the founding document of the Hague-based International Criminal Court, lists pillage as a war crime in international armed conflicts. The Hague Regulations on War on Land of 1907 already prohibit pillage under all circumstances, as does the Fourth Geneva Convention on the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. After the ratification of the Rome Statute by Switzerland, the war crime of pillage was also incorporated into the Swiss Criminal Code.

©

Imago / SNA

©

Imago / SNA

According to international law expert Nina Burri, the exploitation of natural resources in occupied territories is not permitted with very few exceptions. It is specifically prohibited in cases in which, on the one hand, the 'transfer of property’ was involuntary, meaning that the consent of the former owner was either not given, or only given under coercion or threat of other disadvantages. And, on the other hand, if the proceeds of the resources are not exclusively used for the benefit of the local population. The law firm Global Rights Compliance has firmly established that “Russia’s goal appears to have been to fund its own war effort” through the export of plundered grain and is not using the proceeds for the benefit of the local population in the occupied regions in Ukraine.

According to Burri, it is particularly important to note that "in accordance with case law, the establishment of 'legal‘ companies with the specific aim of carrying out these transactions as well as the issuance of concessions or laws by the Russian occupying power cannot legalise plundering". In addition, according to Global Rights Compliance, the use of railways and ports to export unlawfully acquired grain could be in violation of customary international law, i.e., the notions of legal norms generally recognised by states, which exist and apply independently of codified international law.

Indirect appropriation can also be a war crime

In the assessment of the responsibility of companies for plundering, indirect appropriation is also relevant and can itself represent an act of plunder. Thus, a company does not necessarily have to be involved in the original unlawful act of appropriation; the purchase of plundered goods alone may be sufficient for a company to be considered as a “perpetrator” committing pillage, as stated in the manual Corporate War Crimes: Prosecuting the Pillage of Natural Resources from the Open Society Justice Initiative. It lists over two dozen court cases, in which companies or their representatives were convicted in the past for purchasing plundered goods during wartime.

In an opinion piece in Swiss newspaper Le Temps in July 2022, the Swiss Federal Prosecutor Stefan Blättler stated that crimes can be committed far from a current conflict and still be directly linked to it.

He pointed out the offense of pillage and stressed that “the marketing of pillaged commodities could constitute a war crime”.

He also stated that the Federal Prosecutor’s Office intended to advance case law in Switzerland and that in this regard, legal proceedings had already been initiated.

©

Stringer/AFP

©

Stringer/AFP

No sanctions against trade in plundered grain

In response to Russia’s war against Ukraine, the European Union has imposed sanctions, which Switzerland has also adopted. These include a ban on imported goods from the occupied regions that do not have a Ukrainian certificate of origin. However, in their current form, they offer hardly any leverage against the transit trade in plundered commodities. Since the commodities traded by Swiss agricultural traders – whether of Ukrainian, Russian, or other origin - almost never touch Swiss soil, but are intended for third countries, these transactions are not covered by the relevant Swiss sanctions ordinance.

However, according to international law expert Burri, business activities in the context of an armed conflict are per se sensitive and require particular due diligence on the part of companies. Therefore, special caution is required in trading grain from the Black Sea region.

The traders involved must look out for the common warning signs with respect to trade with potentially plundered goods.

These include paying a price far below market value, the secret handling of a purchase or other suspicious circumstances, such as the use of sanctioned means of transport and port terminals, or the purchase from newly established companies.

Particular attention must be paid when business partners are controlled by a warring party or the occupying power. Such caution is a prerequisite to ensuring that companies do not directly or indirectly supply, fund, or provide essential products or services to any of the parties to the conflict through their supply chains.

Increased due diligence is essential

According to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies must, as a matter of principle, ensure that their activities do not violate human rights and the environment. This applies notably to business activities in conflict-affected areas and in countries that are subject to sanctions. To this regard, there are specific guidelines, such as the UN Guide "Heightened Human Rights Due Diligence for Business in Conflict-Affected Contexts". This states, for example, that companies must avoid “causing, contributing to, or being directly linked to the exploitation of the resources of the territory not for the benefit and without the consent of the local population including providing support to the exploitation of natural resources by the occupying power in the occupied territory”.

The agricultural traders ought to be aware of the extensive coverage of the systematic plundering of grain in Ukraine by the Russian forces. Accordingly, they ought to carry out enhanced due diligence. Failing to do so, or doing so inadequately, poses a considerable risk to the Swiss commodity trading hub central for trade in grain from the Black Sea region.

©

Nariman El-Mofty/Keystone/AP

©

Nariman El-Mofty/Keystone/AP

Swiss Black Sea Trade

The grain trade from the Black Sea region is dominated by international trading houses; however, since the war in Ukraine, it has also been increasingly controlled by Russian companies. The leading global agricultural traders, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC), as well as Cofco International, Olam and the Export Trading Group (ETG) trade in wheat, corn, sunflower oil and fertiliser from Russia and Ukraine. These transactions normally take place through their Swiss offices. In addition, smaller traders such as Sierentz in Geneva or Vivalon in Zug specialise in the grain trade from the region.

There are also many Russian traders who operate branches in Switzerland. Aston, one of the largest Russian grain traders, has two offices in Lausanne, including Aston Agro-Industrial which is responsible for international trade. Moreover, Aston operates a joint venture for corn processing with ADM, the world's second largest agricultural trader based in Canton Vaud.

Another Russian agricultural giant, Steppe Agroholding, also has its international trading arm Steppe Trading in Lausanne. The status of their joint venture with Swiss trader LDC, called RZ Agro, which grows grain on its own land in Russia, is unclear. On enquiry, LDC declined to comment on this.

The fifty percent Russian state-owned United Grain Company OZK, which is allegedly involved in the transport of Ukrainian grain in the occupied territories, also used to operate its international trade arm in Switzerland. In the meantime, the group ceased to exercise control over Grainexport SA which is registered in Lausanne, according to an audit report from 2023, and the related OZK website can be found only via the web archive. However, Grainexport is still registered in Lausanne, and is managed by two Russian citizens, among others.

Opacity as a business model

The Swiss commodity trading hub is still relevant for the Russian grain business. However, the extent and the involvement of Swiss traders is not entirely clear. In the spring of 2022, some promptly deleted information about their Russian activities from their websites. Others, such as Geneva-based Sierentz, whose website consists of a single page, never published anything in the first place.

©

Efrem Lukatsky/Keystone/AP

©

Efrem Lukatsky/Keystone/AP

We contacted all the above-mentioned traders in December 2023 and January 2024. Eight out of nine did not comment on any activities or investments in Russia. Like most of the others, Sierentz also left our enquiry unanswered. Although we personally handed our business card to the receptionist in their Geneva office with the request to be contacted, the company never responded.

At the beginning of the war, some traders had (temporarily) put their investments in Russia on hold. However, none of them wanted to withdraw completely from the Russian market, because Russia, being the largest wheat exporter, is too relevant for global food security. Meanwhile, the Russian state tried to increase its control over its grain exports, making it increasingly difficult for foreign companies to obtain the documents required to export their own grain. In addition, the Russian government threatened to nationalise foreign subsidiaries if companies were unwilling to sell them (often below value).

Partial exit from the Russian business

Thus, global traders such as Cargill or LDC were forced to withdraw gradually from their physical business in Russia. According to their own information, they ceased their procurement of grain, as well as storage or loading in Russia in July 2023. Moreover, they wanted to examine the potential sale of their logistics facilities on site. However, it is not possible to verify whether this has happened in the meantime, because we have not received a response from any trader in this regard either.

What is certain is that most of them intend to continue trading in Russian grain.

For example, Cargill confirmed to S&P Global that they still intend to purchase and sell Russian grain. A spokesman for the Russian Union of Grain Exporters declared that “Cargill has made a decision to close one of its business lines but not to leave the Russian market”. Also, according to export databases, it appears Swiss traders are continuing to trade Russian agricultural products.

As a result of the systematic pillage of Ukrainian grain, which is either passed off as Russian grain or mixed with it, Russian grain trade poses an increased risk. Due to their forced withdrawal from Russia, Swiss traders are no longer in control of the procurement, storage and loading of the grain. Instead, they buy it from Russian exporters to sell it on the world market.

©

Mihalchevskiy/Imago/SNA

©

Mihalchevskiy/Imago/SNA

Enhanced due diligence – non-existent?

To ensure that no plundered commodities are present in one's own supply chain, enhanced due diligence in trading with Russia is therefore imperative. However, none of the nine traders we approached about this, has publicly available information regarding the trade involving entities in the occupied regions, or mentions the very specific risks associated with plunder in Ukraine. Even on enquiry, hardly any trader wanted to make specific statements regarding their enhanced due diligence.

LDC and Cofco International indicated that they comply with the respective laws and ensure the legitimate origin of the commodities. Cofco International also stated that there are internal regulations, albeit not intended for the public.

A Zug-based commodity trader does not shy away from risk

A report by Swiss newspaper NZZ published at the beginning of 2024 highlighted why this business is currently extremely delicate. According to this article, the Zug-based commodity trader Vivalon AG bought 11,500 tons of wheat from a Russian company last October. The latter is said to have carried out the export on behalf of the above-mentioned Russian company GZO, which is registered in the Russian commercial register in occupied Ukrainian Melitopol. The San Cosmas, a US-sanctioned ship with a deactivated position signal, allegedly picked up the cargo in Sevastopol in occupied Crimea and transported it to Turkey. There, according to NZZ, it was received by the Turkish subsidiary of Vivalon. Vivalon told NZZ then that its own investigations into the cargo had concluded that there were no issues.

The Ukrainian volunteer-led news portal Myrotvorets had already documented and published information regarding this trade in September 2023. Interesting detail: it appears that the ship was loaded in the port of Sevastopol, more precisely at the Avlita grain terminal, whose operator, the Avlita Stevedoring Company, is on the sanctions list in Ukraine, as well the EU and therefore also in Switzerland – precisely because plundered grain is regularly exported via the terminal.

©

PlanetLabs / SkySatCollect

©

PlanetLabs / SkySatCollect

The Russian wheat business seems to be crucial for Vivalon. Public Eye was able to view Russian customs data, which detail just under 40 shipments of Russian wheat with Vivalon as the buyer between the start of the war in February 2022 and April 2023. This is not necessarily illegal, as the trade in Russian grain is not sanctioned; however, it is a risky business. What the NZZ article did not say: the grain shipment aboard the San Cosmas was probably not the only one that Zug-based Vivalon purchased from the Black Sea region and which the Russian state-owned company GZO, based in an occupied region of Ukraine, was involved in.

Via the trade database Globalwits, Public Eye was able to view another set of Russian customs declarations, showing that Vivalon had already purchased four grain deliveries from a Russian exporter called Samson in September 2023. The declarations all list GZO as the shipper and declarant of the cargoes. At the end of October 2023, another such transaction was carried out. Total value of the five cargoes: US dollar 4.8 million.

Upon enquiry by Public Eye, Vivalon states that they “never had any contact with and do not have transactions with the US-sanctioned entity GZO”. Further, Vivalon writes that a thorough and exhaustive “internal investigation was conducted by Vivalon in response to the allegations presented in the NZZ”. The report, which Vivalon made available to Public Eye, states the following about the cargo in question: "(...) further analysis on our side, combined with the information we have learned from the NZZ article, although not a hundred percent conclusive, shows that there is the possibility of the goods to be stolen”.

The report also “illuminated critical areas” where Vivalon’s robust compliance “proved insufficient in the face of sophisticated and unconventional risks associated with international grain trade”. In particular, Vivalon points out: “Specifically, the oversight regarding the vessel's sanction history and the reliance solely on provided documentation without independent verification have been identified as important compliance gaps that need to be addressed.” Vivalon announced further that corrective measures were being taken, including enhanced due diligence procedures.

©

Dmytro Smolyenko/Nurphoto/AFP

©

Dmytro Smolyenko/Nurphoto/AFP

Conclusion and demands

The systematic plunder of grain in the occupied Ukrainian territories and the lack of evidence of enhanced due diligence on the part of Swiss agricultural traders once again demonstrate the great political risk associated with the activities of the Swiss commodity trading hub. To minimise this risk, Parliament and the Federal Council need to fill the regulatory gaps that have been well-known for some time.

Comprehensive due diligence and a supervisory authority

Our analysis shows that the biggest Swiss-based agricultural traders have yet to prove that they carry out enhanced due diligence to ensure that no plundered commodities enter their supply chains. The applicable legal provisions regarding human rights due diligence are weak and incomplete when compared internationally. Therefore, Switzerland must introduce comprehensive legislation in this regard, as was decided by the EU in December 2023.For ten years, Public Eye has also been calling for a legal framework specifically aimed at the Swiss commodities sector and for an independent supervisory authority to monitor its implementation. As well as enforcing due diligence obligations to ensure the protection of human rights and the environment, such a commodities supervisory authority would prevent the placing on the market of illegally, i.e. criminally acquired commodities, and sanction violations.

Extension of sanctions

The Swiss sanctions regulations do not currently offer any leverage to prevent trade in plundered commodities from Ukraine, as they do not cover transit trade by Swiss companies. However, this transit trade is precisely the core business of Swiss traders. To prevent trading in plundered commodities – knowingly or not – by Swiss companies it is essential that the Swiss Ordinance on measures in connection with the situation in Ukraine be extended to transit trade.Moreover, all those companies and individuals, who were or are demonstrably involved in the unlawful appropriation of commodities and/or infrastructure as well as the export of plundered commodities from Ukraine, should be consistently sanctioned. Considering its geopolitical importance as probably the most significant commodity trading hub in the world, Switzerland ought to adopt independent sanctions in this regard or at least advocate to the European Commission to ensure that the EU extends their sanctions to that effect.

- Prosecution for violations of international law

Moreover, trading in plundered commodities must have consequences under international law for companies because commercial actors involved in transactions of plundered goods and commodities may be considered as perpetrators in the plunder, even if they were not involved in the original appropriation in the conflict or war zone itself. Since such violations of international law are subject to the principle of universal jurisdiction, the law enforcement authorities in Switzerland can also investigate any leads.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the Kyiv School of Economics, Myrotvorets, Yörük Işık of the Bosphorus Observer, as well as The Counter at SOMO, for the data and background information for this research. Responsibility for the content lies solely with the authors.

* The transliteration from Ukrainian is used for the names of cities and regions in Ukraine instead of the Russian transliteration commonly used (e.g. Odesa instead of Odessa).