Plundering of grain in Ukraine: “The EU and Switzerland must sanction intermediaries that enable such activities”

©

Imago / SNA

©

Imago / SNA

The interview was conducted by Agathe Duparc.

More than three years since the launch of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, what is the situation in Ukraine’s agricultural sector? Has it been badly hit?

It goes without saying that the occupation of parts of Ukraine, rich in agricultural land and vital infrastructure, has taken a severe toll on our agricultural sector. Russia has targeted silos in the ports of Odesa and Mykolaiv, as well as numerous agricultural facilities across the country. There has been a decrease in areas being farmed, yields have fallen, and harvests have decreased. However, with its strongly rooted agricultural tradition, Ukraine continues to sow crops, export produce and influence global markets. Despite the losses, it continues to be a major player in the agricultural sector.

Russia has always been Ukraine’s major competitor on the agricultural market…

Yes, especially for wheat, where we were direct competitors. The theft of Ukrainian grain started in the very beginning of Russian aggression, and everything seemed to have been planned. The ships exporting most of the plundered grain had been purchased at the end of 2021, just prior to the invasion, by Crane Marine Contractor, which is part of a state holding company, the shipbuilding company OSK, currently subject to sanctions. The Avlita grain terminal (renamed Aval by Russia) in Sevastopol, Crimea, which is the transit port for this grain, is also part of this holding company’s assets. This is Russia’s policy: capitalizing on Ukraine’s agricultural resources and competing with us in the global grain market.

Recently, several European media outlets have reported drone attacks on farmers in the Kherson region. Has this become a common occurrence?

Yes, this is now happening very often in this region. These drones fly short distances, either to scout locations or to engage in actual manhunts. All credit is due to the heroism shown by agricultural operators. Some farmers cultivate fields that have been completely mined. People are frequently injured.

©

Reuters / Ueslei Marcelino

©

Reuters / Ueslei Marcelino

Does anyone have any idea as to the quantities of grain plundered by Russia?

According to NASA’s food security programme, production output in occupied Ukrainian territories is between 6 and 8 million tonnes of grain. According to our calculations, more than two million tonnes have been exported via the ports located in Crimea. But another part of the grain is transported by road. We have documented a steady flow of tankers transporting grain from Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson to the Russian region of Rostov, where it can be sold as Russian, thanks to falsified documents.

Where does Russia sell the grain from the occupied Ukrainian territories?

Most of the stolen grain is exported, with the volumes consumed in Russia being very low. In the months following the invasion, Turkey was the main destination for this grain. But when presented with the revelations by many international media outlets that had investigated these practices, Ankara put an end to its involvement. Some of the vessels involved have been sanctioned, but by no means all of them. No significant action has been taken so far by the international community against the actors involved in this trafficking operation, which continue to find new opportunities.

Where are these new opportunities emerging?

After Turkey, Syria took over, as part of a government programme, via its public grain producer. Since the fall of Bashar Al-Assad in December 2024, the observations in ports indicate, however, that Syria is now closed to Russia, although there are still a few isolated cases. For example, we recently tracked a ship that made the trip twice between the port of Feodosia (Crimea) and Tartus, Syria. The Russian Federation is still exploiting the instability and shortage of food to bring the stolen grain to the region. But these exchanges are no longer part of state policy. Everything has now moved to Egypt, which has opened its doors wide. Currently, almost all ships leaving Crimean ports with stolen grain are destined for Egypt.

Egypt probably cannot consume all the grain it buys. Which countries does it sell part of these shipments to?

Unfortunately, we don’t know. We assume that Egypt operates as a hub, with grain being unloaded there, then reshipped elsewhere. The documents and certificates provided by Russian exporters are falsified. They never mention the actual region of production – such as Crimea, Kherson or Zaporizhzhia – but only “Russia” or the address of a Russian exporting company. This means that the stolen grain can be resold to any buyer, including in the European Union or in Switzerland.

Russia has a long tradition of bartering. Before the war, it entered into several such agreements with Iran, whereby in exchange for Russian agricultural products or industrial equipment, it received Iranian oil. Last year, an Iranian newspaper even mentioned the possibility of exchanging Russian grain for weapons supplied by Tehran. Are you aware of such practices? Is it possible that the grain plundered from Ukraine is incorporated into these opaque barter arrangements?

Unfortunately, the Russian authorities have shut down access to many official databases and registers, preventing us from getting an overview of grain flows. There are a few clues still available. Under Bashar Al-Assad’s regime, for example, Russia delivered grain to Syria at abnormally high prices: up to US$ 375 per tonne, compared to the actual market price of around US$ 225-250. Why this difference? Did these consignments include items other than wheat? We don’t know. We have also recorded a sale of grain to Iran, this time at a price below the market price, without being able to find out why.

In an interview you recently gave to the Polish press, you mentioned in May 2025 the active role played by some Ukrainian embassies in preventing the import of plundered grain.

Ukrainian embassies are trying to take action in the countries where these shipments arrive. They regularly ask us to prepare notes of protest against the reception of certain ships, attaching relevant documents and evidence. But in Egypt, where this is a huge issue, these actions have so far not reaped any rewards.

Sometimes this kind of heads-up works. Last May, Lebanon refused to receive a ship loaded with stolen Ukrainian agricultural products…

Yes, we were able to establish that the grain came from Berdyansk, in Zaporizhzhia Oblast (region) occupied by the Russian armed forces. It had been loaded at the port of Feodosia (Crimea) on board the Russian ship Nikolai Leonov, which first travelled to the port of Temryuk (a river port on the Sea of Azov), before leaving for Lebanon with false documents of origin. Having been alerted, the Ukrainian embassy issued an official note, attracting the attention of the local media. Lebanese traders became aware of the reputational and financial losses suffered by the ship’s operator. Thanks to this display of vigilance, such an attempt is unlikely to happen again.

Switzerland is home to many grain traders. Has the Ukrainian embassy ever contacted the Swiss authorities to report a problem?

Unfortunately, I am not aware of any action taken in Switzerland so far. However, I’m interested in any information you may have on this subject.

In February 2024, Public Eye investigated the agricultural trading company Vivalon, based in Zug, Switzerland. It is suspected of having indirectly purchased grain originating from the occupied territories. To what extent does Switzerland bear responsibility in relation to this plundering of grain?

Switzerland is closely implicated in the global agricultural market, being home to numerous trading companies that benefit from tax advantages, not to mention its banks that finance transactions. We shouldn’t forget the certification companies that inspect the merchandise. Against this background, the Vivalon case is very revealing. In addition, Russian companies are continuing to maintain active links with Switzerland, whether through their subsidiaries or partnerships.

©

Public Eye / opak.cc

©

Public Eye / opak.cc

Read Public Eye's investigation into Russia's plundering of Ukrainian grain (2024).

No one is really safe from finding themselves, at the end of the chain, with grain stolen from Ukraine…

The transactions we have analyzed are often very complex. The grain is resold several times, with companies based in the United Arab Emirates or Hong Kong regularly involved in these operations. It is therefore conceivable that Swiss companies or banks may be involved in these chains, by buying this grain or participating in the transaction.

A recent investigation carried out by Radio Svoboda clearly highlights the problem. A European company, greatly concerned about its image, had bought some grain, making sure that it had not come from the occupied regions. It had been issued with a certificate confirming the grain’s “clean” Russian origin. But it was nothing of the sort. This has dealt a very severe blow to the company’s reputation.

Under these circumstances, what message can be sent to agricultural traders who continue to buy Russian agricultural products, a business that is not sanctioned?

We can no longer turn a blind eye, as the grain trade with Russia nowadays entails major risks. Obtaining any reliable guarantees is almost impossible.

Even a document certifying that this grain does not come from the occupied territories can be faked. For the time being, you have to consider quitting this market or, at the very least, tightening up considerably the checks carried out on the grain’s origin, which remains very difficult in practice.

A few months ago, sanctions were imposed by the European Union and Switzerland on the Russian state-owned grain operator GZO, which operated from the occupied territories of Ukraine. The Swiss company Vivalon had also indirectly dealt with this company according to export data. Does this mark an important step forward?

Yes, it’s certainly a step in the right direction. But the Russian aggressor is still finding ways to get around sanctions. Until recently, GZO sometimes appeared as a grain supplier. Now its name has been replaced by that of a series of shell companies created to cover its tracks. The EU and Switzerland must take further action and apply secondary sanctions, which also target foreign intermediaries and partners that facilitate these operations.

How did the SeaKrime project in which you are involved come about?

The SeaKrime project was launched in October 2016, two years after Russia annexed Crimea. It all started when a ship arrived at the port of Feodosia, in Crimea, to unload its cargo under particularly suspicious circumstances. Crates – similar to military crates – were unloaded at night, under guard, in the dark, with flashlights being used as the only source of light. We were unable to ascertain what was going on exactly, but our investigation caused quite a stir, highlighting that the ports of Crimea, which were in theory closed to navigation, continued to operate. This subject went beyond the Russian–Ukrainian conflict and concerned international maritime trade and its grey areas, which prompted us to document these illegal shipments and specialize in this issue.

Since February 2022, your workload has increased…

Indeed, since the launch of the full-scale invasion in 2022, we have seen a sharp increase in grain exports from Crimean ports. With the volumes increasing every month. This made no sense, as the 2021 harvest had already been largely exported. We then realized that this was grain stolen from silos seized by the Russian army and belonging to Ukrainian companies, particularly in the Kharkiv region. This grain did not only pass through Crimea as trucks also transported it to Russian ports on the Baltic Sea, such as St. Petersburg or Ust-Luga, for export.

What tools do you use to establish these facts?

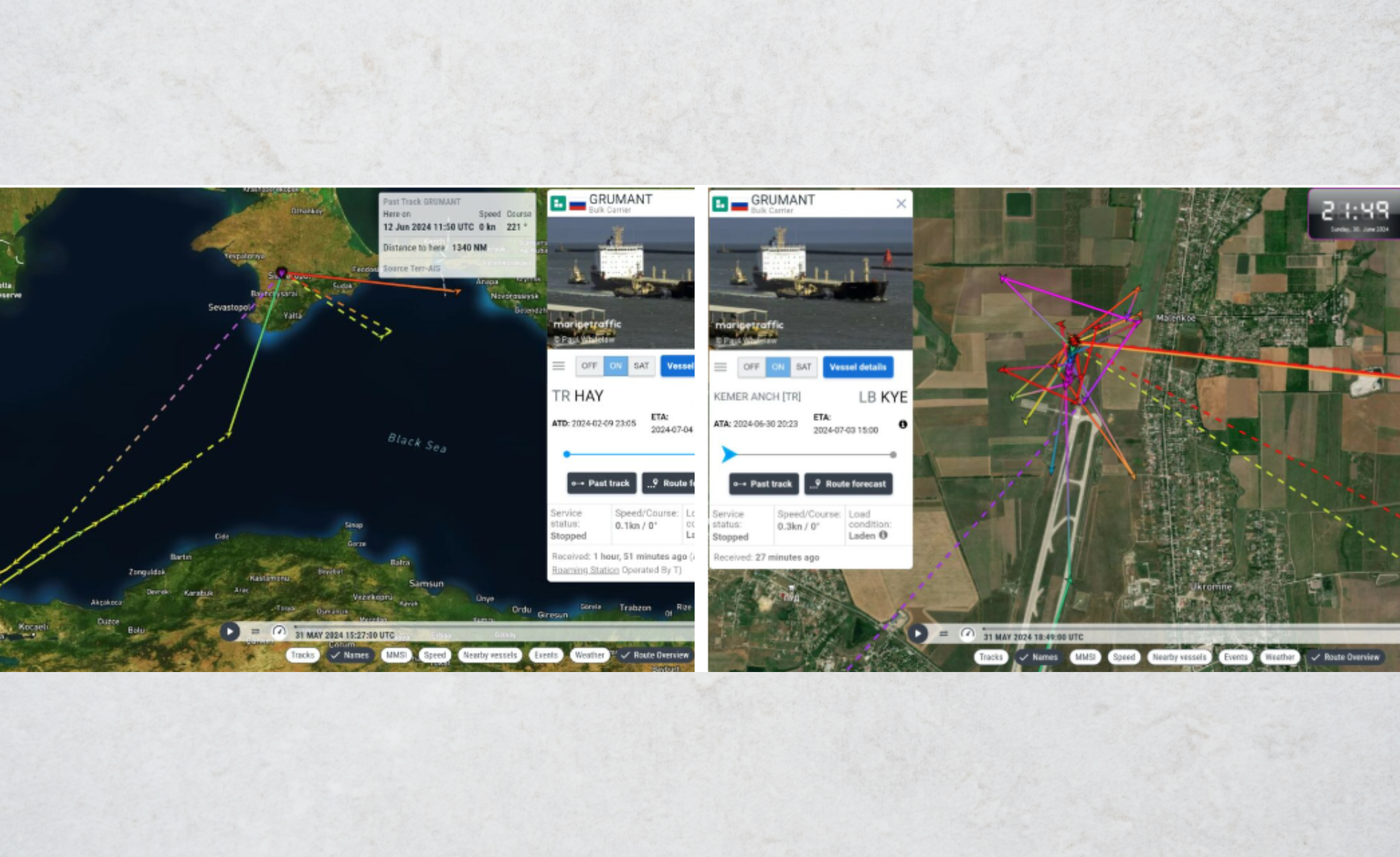

We mainly use OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) tools, which are publicly available on the internet. Marine Traffic (a ship tracking site, editor’s note) allows us, for example, to track ships in real time thanks to data from the AIS (Automatic Identification System). But a good many of the vessels involved in transporting illegal shipments deliberately disable their AIS, making it impossible to locate them. Others use signal spoofing, a common practice in the Black Sea, where AIS data is falsified to make it appear that a ship is somewhere else or following a different route. So, it’s not enough just to have open sources. That is why we also rely on sensitive information supplied by sources located in the occupied territories. We also monitor social networks and use maritime databases like Equasis.

What is the ultimate objective of these investigations?

Our aim is to document the massive exporting of grain via Crimean ports. We are also interested in investigating the systematic theft of Ukrainian agricultural equipment, often state of the art and fitted with advanced technologies such as GPS. Ukrainian Combine harvesters have been found as far away as Chechnya, while entire silos have been moved. We must not forget that this equipment belongs to real, living people.

Behind this plundering, there are always victims, human tragedies.

Numerous criminal proceedings have been opened. Even if some facts might remain hidden for 1, 5 or 10 years, they will eventually be uncovered, because Ukraine is really determined to shed light on these issues. As for the companies complicit in these actions, whether involved in the supply chain, financing or trading, they will eventually be unmasked too. And they will have severe consequences to face, undoubtedly resulting in them losing their reputation.

* The Myrotvorets Center was created in late 2014. It is an independent, non-governmental organization for “Research of Elements of Crimes against the National Security of Ukraine, Peace, Humanity, and International Law” which provides information, in particular destined for “law enforcement authorities and special services.” Some of its actions are the subject of criticism, such as the publication on its website of the personal data of individuals considered to be “enemies of Ukraine.” But aside from that, its expertise is widely recognized. The investigations carried out by its SeaKrime monitoring program have fueled journalistic inquiries around the world.