Excess profits War and crises – and commodity traders are making record profits

Silvie Lang and Manuel Abebe, with input from D. Mühlemann & A. Budry Carbó, January 19, 2023

According to the World Bank, the impacts of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine pushed up to an additional 95 million people into extreme poverty in 2022. At the same time, the current uncertainty in terms of energy supply has pushed the prospect of a shift away from fossil fuels even further out. In contrast, a small group of companies is proving not only resilient, but extremely profitable through these times of crisis – commodity traders.

Traders of oil, gas, coal, wheat or corn are directly profiting from increasing demand, higher prices and massive fluctuations on commodity markets. In June 2021, The Economist ran an article entitled:

«As food prices soar, big agriculture is having a field day.»

Other media outlets such as the agencies Reuters and Bloomberg or the Wall Street Journal outdid each other with reports on the bonanza enjoyed by the commodity traders as a result of the pandemic, extreme weather events such as droughts or bottle necks caused by wars.

The profitable business in foodstuffs

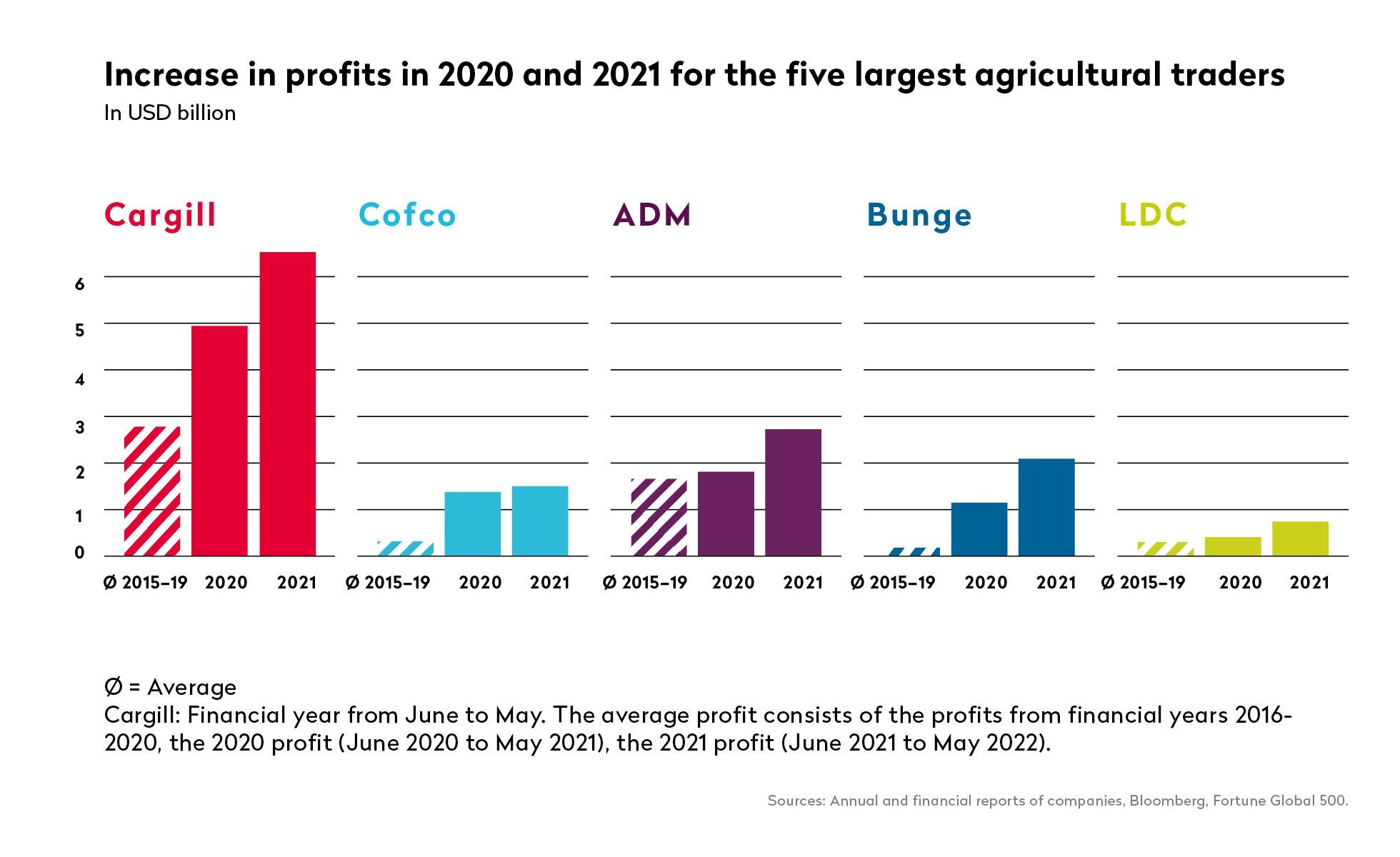

The Covid-19 years of 2020 and 2021 already saw an increase in profits for most traders. These secretive companies which carry out most of their trading business in Switzerland, did even better in the first half of 2022, achieving record profits. In the financial year from June 2021 to May 2022, the world’s largest agricultural trader Cargill, whose global trading and freight business is headquartered in Geneva, increased its profits by 141% compared to the average prior to the Covid-19 crisis. The news agency Bloomberg disclosed the company’s record profits of nearly USD 6.7 billion – Cargill has not disclosed profits since 2020. It did not obtain any comment on the matter from the trader.

The other large agricultural traders also made record profits in the years of crisis. For instance, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) which has its second largest trading hub behind the US headquarters in the town of Rolle in Vaud canton, described 2021 as a «watershed year» with the highest profits of its nearly 120-year history.

Various business developments can cause traders to face significant fluctuations in profits. For instance, in 2019, Bunge booked a loss of USD 1.3 billion. With profits of over USD 2 billion in 2021, the trader has long since made this back. Since 2021, traders’ performance are uniformly trending upwards – a development confirmed by the business figures for the first half of 2022. ADM for instance was able to once again increase its profit and, with nearly USD 2.3 billion in the first half of 2022, it has already made nearly as much as it did in the full year 2021.

The same goes for Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) which has its operational headquarters in Geneva. It enjoyed a dazzling first half – LDC nearly doubled its profit compared to the same period the previous year. Its 2022 mid-year report makes clear that LDC and its competitors flouris especially in times of crisis. «Strong performance in a context marked by global market uncertainty and supply chain disruptions (…) and concerns over the resurgence of Covid-19, particularly in China, amplified in H1-22 by the Russia-Ukraine crisis.»

Oil, gas and coal pour in

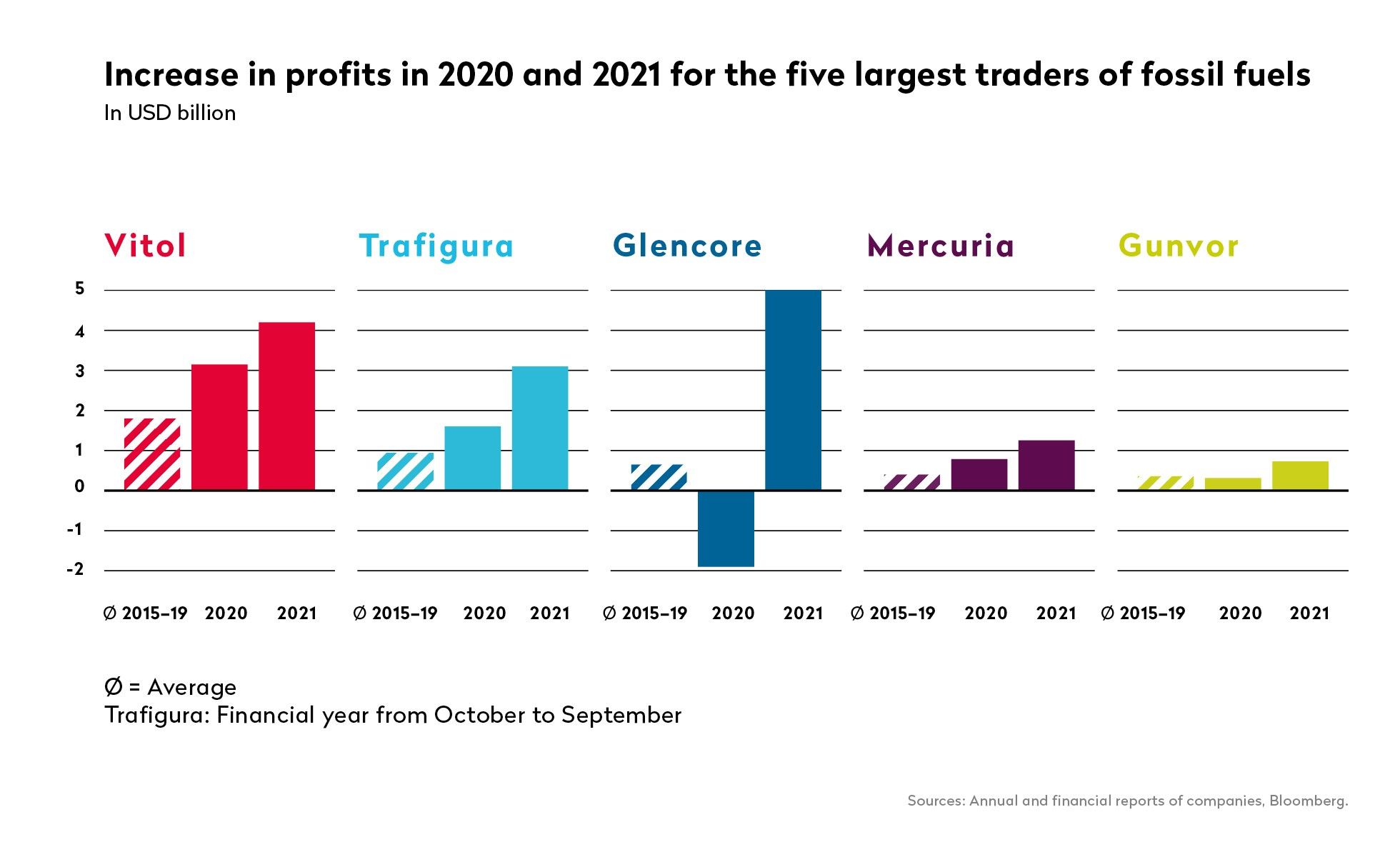

The trade in oil, gas and coal is thriving too – especially in times of logistics bottlenecks, sanctions and efforts to move away from fossil fuels. Vitol, the trader with the highest turnover, beat its own record, increasing its profit from USD 4.2 billion in 2021 to 4.5 billion in the first six months of 2022, according to Reuters – the trading giant does not disclose official mid-year figures.

Trafigura which also has its global headquarters in Geneva, managed to increase its 2021 profits by 230% compared to its pre-pandemic average. CEO Jeremy Weir considers this to be the firm’s own success and says that Trafigura had «once again skilfully mastered a broad range of commodities in a period of extreme market volatility and performed exceptionally well despite market conditions». Trafigura proves how profitable the traders have been during the crises with its profit for the 2022 financial year (October 2021 to September 2022). With USD 7 billion, Trafigura more than doubled its record profits of 2021.

According to Bloomberg, the Geneva-based Mercuria also achieved its best result in the company’s history in 2021. Mercuria does not disclose mid-year figures either. However in the first half year of 2022, Gunvor, which is domiciled just 100 metres down the mundane Rue du Rhône from Mercuria, quadrupled its profits versus the first six months of 2021.

The main beneficiary of the crisis

One commodity trader however outpaced all others with its rising profits: Glencore. According to the Financial Times, the Zug-based company is «one of the biggest winners from the turmoil in commodity markets unleashed by the war in Ukraine». Glencore had booked huge losses both in 2015 as well as in 2020, primarily related to the extractives business. However in 2021, the company once again made nearly USD 5 billion in profit. This is an increase of a full 661% as compared to the pre-pandemic average.

As if further proof was needed that neither global health or supply crises, nor wars or sanctions would negatively impact the commodity traders, Glencore supplies it. With a profit of USD 12 billion in the first half of 2022 – an increase of 846% compared to the same period the previous year, the company outshines all of its competitors.

The climate killer coal is partly responsible for this record. The share of the coal business in net profits is not known. In consolidated results (EBITDA, profits before interest, tax and amortisation), the share of coal in the first half of 2022 stood at nearly 50%. This corresponds to a nearly tenfold increase in revenues from the coal business as compared to the same period the previous year. It is no wonder that Glencore’s CFO Steven Kalmin stated that the commodity coal was having its «day in the sun». The climate killer is making a comeback and, as a commodities hub, Switzerland is a significant participant in the process. According to research by Public Eye, some 40% of global trade in coal is transacted through Switzerland.

©

CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

©

CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

The commodity billionaires

Yet who really benefits from this giant flood of money? The traders’ secrecy is an integral part of their business model. Ownership structures are kept as secret, as are possible connections to oligarchs. These are only revealed following laborious research, if at all. Nevertheless, it is clear that a few individuals are really raking it in.

In the case of Glencore, the increase in share price significantly boosted the wealth of Ex-CEO Ivan Glasenberg, the second largest shareholder after Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund. According to the business magazine Bilanz the value of his shares increased from CHF 1.6 billion to 6.7 billion from January to August 2022. With a total net worth of CHF 7.5 billion, Glasenberg features on Bilanz’s 2022 list of the 300 richest people in Switzerland. Gunvor on the other hand is 87% privately owned by Swedish Torbjörn Törnqvist, whose net worth has nearly doubled since early 2021 according to Bloomberg. With over CHF 3 billion he also makes it into the top 300 wealthiest. At Mercuria, it is above all top management and the company’s founders Marco Dunand and Daniel Jaeggi who reap the benefits. The total net worth of the two men is estimated by Bilanz at CHF 2.2 billion, which recently made them into Swiss trading billionaires. With a net worth of CHF 475 million, Trafigura’s CEO Jeremy Weir is also in the top 300.

The family around Margarita Louis-Dreyfus, Chair of the LDC Board, is also in the super wealthy club with a current net worth of CHF 3.2 billion. That’s nothing in contrast to the extended family of William Wallace Cargill, the founder of the privately owned Cargill – with its collective wealth the family ranks 11th among the richest families worldwide. According to the NGO Oxfam, since 2020 their wealth has grown by USD 20 million – per day. It is no surprise then that Bloomberg calls the commodity trader «one of the most lucrative cash-machines in corporate America». The profitable financial year from June 2021 to May 2022 catapulted three further successors of the founding fathers onto Bloomberg’s list of the 500 richest people in the world. The family now includes eight commodity billionaires.

This wealth may seem somewhat cynical in the case of the company that claims to be responsible for feeding the world. With profits of nearly USD 6.7 billion, Cargill would be able to single-handedly make up the World Food Programme’s budget deficit of USD 5.2 billion. Cargill donated just 0.1% of its profits, USD 10 million, to the chronically underfunded UN agency in 2022.

Integrated value chains and information monopoly

Yet what makes these secretive commodity traders so profitable? One key reason for their epochal crisis profits lies in their business model. The former «logistics» companies that simply shipped commodities from A to B have long expanded their activities. Some have entered agricultural production and manage plantations. Others operate mines, refineries or networks of petrol stations. Nearly all offer in addition a wide range of logistics services. The five largest agricultural traders operate nearly 1,300 ships, of which 650 are run by Cargill from its headquarters in Geneva. Traders of oil, gas and coal have long been active in ocean shipping. Trafigura alone operates a fleet of over 900. A subsidiary of Gunvor states that it is one of the largest charterers of tankers in the world. Mercuria, Vitol and Glencore are all involved in shipping via subsidiaries.

©

AFP

©

AFP

The photo shows a Cofco plant near Sorriso, in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.

Their global logistics networks, wide ranging portfolios and central positions between commodity supply and demand, paired with their access to financing all make traders resilient to crises. However, what makes them truly profitable is their exclusive access to market information.

They anticipate the at times extreme fluctuations on commodity markets in order to make as much profit as possible.

After the Russian invasion it swiftly became clear that the war would have a dramatic impact on energy and commodity supplies, in particular for Europe. While the price for Russian Urals oil severely collapsed at the start of the war, the price of other grades of crude rose sharply. Gas prices have risen since the EU’s decision to sanction coal and oil from Russia and to reduce its dependence on Russian gas. Commodity companies always benefit from high prices and from price volatility – all the more so when the fluctuations are significant. Against the background of the political failure to manage the energy transition, the traders’ profits are skyrocketing.

A similar trend can be seen in the agricultural markets. Prices for cereals and oil seeds like soy increased initially during the Covid-19 crisis and rose further with the Russian invasion, reaching unprecedented highs. In May 2022, the Washington Post noted that «[p]rice volatility might be bad for eaters - but it’s good for agribusiness, investors, grain speculators» and the traders. In the meantime the markets have calmed somewhat, including as a result of the UN-negotiated Russia-Ukraine grain deal. However, there continue to be certain fluctuations, bringing with them uncertainty.

The companies in Switzerland with the highest revenues

The Russian war in Ukraine shone a spotlight on the trade in oil, gas and coal. Yet, commodity traders remain broadly unknown to the majority of the population despite the fact they have already been leading Handelzeitung’s lists of the companies in Switzerland with the highest revenues for many years. In the financial year 2021, six commodity traders made it into the top 10. However, a few important names were missing.

©

Bloomberg via Getty Images

©

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Even those traders that are not headquartered in Switzerland transact a large part of their business here and should be viewed as Swiss traders. The Federal Government takes the same view in «The Commodity Trading Sector Guidance on Implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights». A list corrected to this effect makes the sector’s dominance in Switzerland even clearer:

Eight of the ten highest-earning companies in the country in 2021 were commodity traders.

The dominance becomes even more visible when one considers that the total of nearly 950 commodity traders in Switzerland, of which a quarter are shell companies, comprise only 0.1% of the country’s 600,000 companies. A small sector of high-earning and profitable companies stands at the head of the Swiss economy. The anticipated 2022 business figures are not expected to change anything about this dominance.

Commodities hub of global significance

Despite the supremacy of this sector there are few official figures available about Switzerland’s commodities hub. A significant reason for this is what is known as ‘transit trade’, i.e. companies in Switzerland organise the physical trade in commodities at a global level, but the commodities in question are neither imported to nor exported from Switzerland and they therefore do not appear in any customs statistics. There is no register for transit trade transactions either.

In addition to this, neither companies nor the Federal Council or Parliament have yet shown willingness to provide reliable statistics for example on Switzerland’s share of global trade in commodities. In the 2018 commodities report, the Federal Council had to rely on estimates from an external study co-funded by the government. Prior to this it had used figures provided by the industry association, Swiss Trading and Shipping Association (STSA). However, the methodology used to calculate the industry statistics remains unclear and as a result the statistics are not reliable. This is confirmed by the STSA upon request.

Due to the politically desired lack of transparency, Public Eye produced its own estimates of Switzerland’s market share in global commodity trade. One thing is sure – Switzerland is and remains the largest commodities hub in the world, for at least half of the global trade in grains is transacted via traders based in the country; the same goes for 40% of coal and every third barrel of crude oil.

Despite the lack of data, the Federal Council does not tire of emphasising that the commodities sector is a significant industry. However, there is no explanation for this given the statistics released by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office that estimates the sector to comprise just 950 companies, nor when considering its estimation that it barely employs 10,000 people.

Commodities sector double the size it was considered to be

A possible benchmark for the real relevance of the sector for Switzerland is the value generated by transit trade, which is assessed by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) (see below). As transit trade is predominantly comprised of trade in commodities, this figure can be used as a proxy for the sector. Indeed, the Federal Council used it in its 2018 commodities report. In 2017, the value from transit trade stood at CHF 25 billion, i.e. a 3.8% contribution to GDP – roughly the same size as Switzerland’s retail sector. The federal administration, media and the sector all refer to the figure of an «approximately 3.8%» contribution to GDP.

More infos

-

Facts and figures about transit trade in Switzerland

As part of Switzerland’s current account, on a quarterly basis the Swiss National Bank (SNB) surveys the goods purchases and sales of Swiss companies in relation to transit trade. According to the National Bank Ordinance, all companies with a quarterly transaction volume in transit trade of over CHF 100,000 must participate in the survey. This includes commodity traders.

The SNB calculates the value created from the information disclosed. The bank calls this indicator net sales in merchanting. It delivers proxies for the full economic relevance of the commodity trade in Switzerland. However, there are some limitations to the figures:

- Alongside trade in commodities, transit trade comprises additional activities. The SNB does record the sales of goods according to type of good which allows for conclusions in relation to the respective activities. The categories of goods relevant to the commodity sector are: energy sources; agricultural and forestry products; metals, non-metallic mineral products. The share of these categories of goods, and thus the share of commodity trade as part of the sales of goods stands at around 85%. However, the SNB only records receipts from the sale of goods and not value generated by category of goods. As a result, it is not possible to safely say whether in terms of value creation, 85% comes from trade in commodities. The SNB’s survey methodology does not allow for the correct share of commodity trading to value generated by Swiss companies in transit trade to be ascertained.

- Not all commodity trading companies are covered in the statistics. According to the National Bank Ordinance all companies that meet the minimum transaction volume threshold are obliged to report. Despite the requirement to disclose, not all of these traders fall into the defined sample. According to the SNB this should not significantly impact the quality of the statistics.

- The transit trade figures are at times heavily corrected years after their initial publication. The reasons for this are the SNB’s revision procedure as well as the lenghty clarifications with trading companies.

- Commodity trading companies are at times active outside transit trading, for instance if they further process a product before sale (e.g. crude oil in a refinery). In the SNB’s jargon this is called ‘manufacturing services abroad’. These earnings are recorded separately in the current account. It is not possible to ascertain the exact share of value generated by commoditiy traders through manufacturing services abroad.

This figure has long been overtaken. In 2019, the SNB revised its data and released the figure CHF 40 billion as the value generated by transit trade for 2017. This equates to 5.8% of GDP which means the commodities sector was then already significantly larger than assumed. Today this is all the more the case:

In 2021, the value generated stands at CHF 58.5 billion. At 8% of GDP, this equates to over double the figure used by the Federal Council and Administration.

The comparison with other sectors further highlights the relevance of the industry for the Swiss economy. Since at least 2012 – the SNB’s revised figures do not go further back – the GDP share of transit trade has been larger than that of the chemicals and pharma industries together. Since 2016, transit trade has outstripped the construction sector too.

Commodities sector will soon be as large as the financial sector

In the private services sector, only the financial sector is even larger than transit trade and thus commodity trade. However, the value generated by the financial sector has remained steady over the past ten years whereas that of transit trade has increased massively.

In 2021, in Switzerland, the value generated by the financial and insurance services sector, including banking, amounted to CHF 66.7 billion – only slightly more than transit trade. This gives the financial sector a GDP share of 9.1%. Transit trade and thus the commodities sector is now nearly as significant as the whole financial sector.

Loop holes in Swiss regulation

The associated risks are a further point of commonality. For years, Public Eye has shone a spotlight on issues associated with the commodities sector, such as cases of corruption or money laundering, human rights abuses, dubious tax deals, the sector’s contribution to the climate crisis or to difficulties in implementing sanctions. In light of these grievances and the growing economic relevance of the sector, it is astounding that neither the Swiss government nor the Parliament are showing meaningful efforts to appropriately regulate the sector.

This is all the surprising as, since 2007, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) has been in place for the equally high-risk financial sector. FINMA oversees compliance with industry regulation, including provisions related to combatting money laundering. Such a legislative framework is lacking in the commodities sector as much as is an oversight body. Moreover, the often quoted «indirect oversight» by banks over the commodities sector, which the Federal Council often uses as a key argument against any form of commodities market regulation, is not effective. It is insufficient or even inexistent.

Tax breaks and loopholes

The Swiss tax regime also offers some loopholes and is not sufficiently corrective to, for example, appropriately distribute the profits made by commodity traders. Quite the opposite, Switzerland continues to opt for low-tax policies and dubious tax breaks. In 1956, tailor-made tax breaks incentivised Cargill to set up its European headquarters in Geneva. Over 60 years later, correspondence between agricultural trader ADM and the authorities of the canton of Vaud, leaked in early 2022, showed that such tax benefits continued to be commonplace for foreign firms. This is despite the fact that, following pressure from the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), Switzerland abolished numerous tax privileges as part of its Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (STAF).

Current international developments seem to give little cause for hope. Reforms proposed by the OECD and G20 to ensure fair distribution of the tax income of companies among states have still not been concluded. The blueprint released contains numerous loopholes. Pillar One, which provides for taxation of profits in the sales market rather than the countries where companies are headquartered, does not cover commodity traders. Pillar Two, which provides a minimum tax of 15% for certain international companies, does not include revenues from shipping.

Whether the reform will ultimately be passed in this form is unclear. However, if it were to be, it would do nothing to undermine the practice of tax dumping in the commodities sector. In addition, the overdue re-distribution would not occur, for it would continue to be possible for company profits to be shifted to home countries of companies such as Switzerland. Resource-rich countries of the Global South would not benefit. As a result, resistance is forming. A resolution demanding the development of an international tax cooperation framework put forward by the Africa Group at the UN General Assembly in November 2022 was unanimously approved. According to the Global Alliance for Tax Justice this is «a first step towards an inclusive, democratic and transparent process to reform global tax architecture». Switzerland also supported the provision, albeit with reservations.

The tonnage tax

Until this comes to pass, Switzerland is likely to spare no efforts in wooing the commodities sector with tax breaks. In the 2018 commodities report, the Federal Council announced the introduction of a special tax for shipping companies. Such companies would no longer be subject to corporate profit taxes, but would be taxed on the basis of the loading capacity of their ships, i.e. the net tonnage. This ostensibly aims to strengthen shipping and Switzerland’s position as a shipping hub. The Federal Council works on the basis of some 60 affected companies with approximately 900 ships and refers to the sector association the STSA. However, in reality the number of ships operated out of Switzerland is likely to be far higher. The largest commodity traders operate over 2,600 ships, many of which they manage from Switzerland, thus far outstripping shipping companies.

As the Federal Council indicated, commodity traders could internally shift profits to ships taxed by tonnage and, in doing so, circumvent profit-based taxes. This was confirmed by industry insiders to Swiss media outlet Sonntagsblick: «The tonnage tax presents one of the easiest opportunities to reduce the tax burden». According to their estimates the traders would continue to expand their transport activities: «For trading companies with their own large fleets there could be significant tax savings, as they will alter their own contracts so the profits flow into the shipping business. »

The tonnage tax therefore constitutes a spectacular privilege afforded to the commodities sector,

despite the fact that the Federal Council consistently states that «Switzerland, as a rule, does not pursue economic policies tailored to individual sectors (…)». It appears that this approach only applies when it comes to reigning in certain industries, but not when it comes to favouring them.

©

AP / Keystone

©

AP / Keystone

Tax privileges over windfall tax

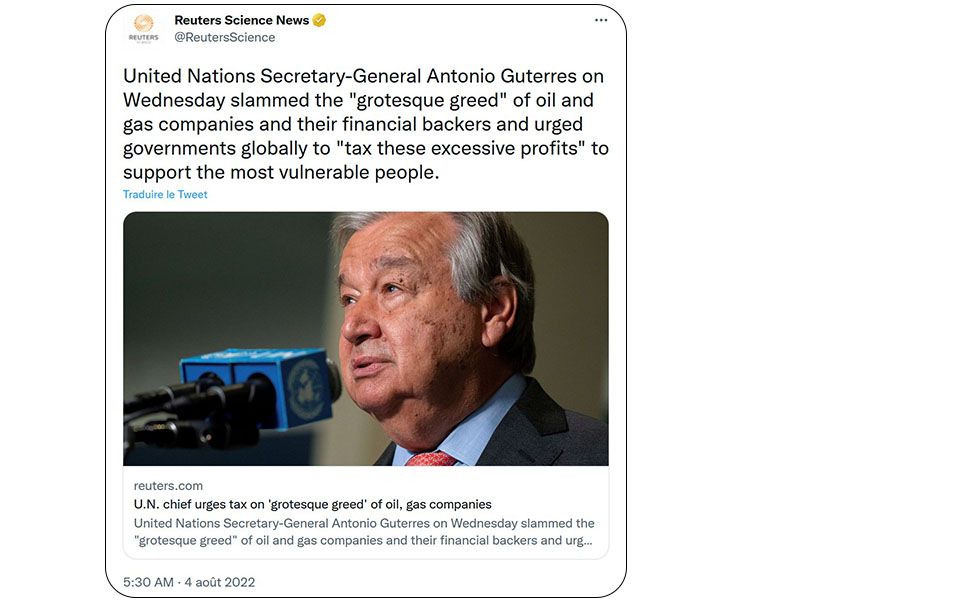

Of all things, the Federal Council and Parliament want to offer tax breaks to precisely those companies that made huge profits in the crisis years. Exactly the opposite would be more legitimate – a special tax on ‘windfall profits’. The targeted profits are directly connected to the traders’ business model, but are significantly caused by external circumstances such as the impacts of the Russian war in Ukraine. This is why they should also be taxed separately.

The International Energy Agency estimates that for example in 2022 nearly USD 2 trillion in windfall gains were generated from oil and gas extraction. In August 2022, UN General Secretary António Guterres accused energy companies of «grotesque greed» and stated that it was immoral for oil and gas companies to be making record profits from this energy crisis off the backs of the poorest people and communities, at a massive cost to the climate. At the UN General Assembly in September 2022 he urged all governments to tax these excessive profits and use the funds to support the most vulnerable people.

The majority of European companies take a similar view. Many have either already introduced windfall taxes, such as Italy, Spain and the UK, or at least announced them. In March 2022, the European Commission adopted measures including the option for temporary windfall taxes in order to minimise dependence on Russian energy supply as soon as possible and to mitigate the impact of high oil and gas prices. In September 2022, the EU Energy Ministers put forward a specific proposal for a windfall tax on energy companies. In the US a corresponding bill is under discussion. Although the development and implementation of the different measures varies significantly and redistribution is only happening slowly, there is international consensus that such windfall profits are illegitimate and should be taxed separately.

Switzerland’s unique path

This is not the case for Switzerland. In June 2022, when responding to a question from Gerhard Pfister, President of the Center Party, on windfall taxes, the Federal Council made it publicly known that it would reject such a motion on the grounds that it would harm Switzerland’s competitiveness and would be hard to calculate. With the EU measures and those of various neighbouring countries, these arguments are off the table and the parliamentary initiative introduced by the Green President and National Councillor Balthasar Glättli in September 2022 should be heard. It demands that «significant windfall profits made due to the war against Ukraine» be temporarily subject to higher federal taxes. It would affect companies from the sectors of energy production and trading as well as the commodity trade and arms production. This would make it possible for windfall profits to be siphoned off and redistributed to those groups in Switzerland, Ukraine and the Global South that are most suffering the impact of the Russian war in Ukraine.

What has to happen now

The laws or regulatory efforts in Switzerland are in no way commensurate to the risks in the commodities sector. The growing economic significance and huge profits that Swiss traders are making in the global crisis renew the need for broad regulation of the sector.

Therefore, Public Eye is calling on:

The Swiss Government and Parliament

-

To advocate within the framework of the OECD/G20 and the UN for a fair, global taxation policy that prevents profits from being moved to home states to the detriment of resource-rich countries.

-

To refrain from tax privileges for commodity traders, such as the tonnage tax, and rather, in the case of so-called war profits, to introduce a windfall tax for the commodities sector and provide for fair redistribution.

-

To improve transparency in the commodities trading sector in Switzerland, in particular by regularly publishing relevant and comprehensive statistics.

-

To introduce a comprehensive due diligence requirement in the field of human rights and the environment for all companies based in Switzerland, including commodity traders, that goes well beyond the currently applicable provisions.

-

To create the statutory regulations and set up a corresponding authority to provide oversight of the commodities sector, including the oversight of compliance with due diligence requirements and sanctions for relevant breaches.

Swiss commodities traders and industry associations

-

To improve transparency in relation to company structures, business results, activities in Switzerland, market share and tax payments.

-

To fully embed in corporate structure and implement comprehensive systems and processes of due diligence on human rights, environment and climate, money laundering and corruption, especially reporting on, preventing and remedying identified risks and violations.